The U.S. and China: The trade war and the broader confrontation

As the “trade war” between the U.S. and China looks set to last, it is time to ask if the confrontation is more about “war” than “trade”. China is simply carrying on the ideological battle initiated by the Soviet Union. The pragmatic Middle Kingdom may back down for strategic reasons, but in the long term, the showdown might intensify.

In a nutshell

- The U.S.-China “trade war” could last 20 years

- The confrontation is part of a greater strategic competition

- The adversarial nature of the relationship is likely to intensify

The tussle between the United States and China has so far, ostensibly, been about trade. It began early this year with American tariffs on solar panels and washing machines against cheaper rivals from South Korea, China and elsewhere. But by mid-2018, China had naturally become the principal target in a wider and more intense tit-for-tat on tariffs.

Seen from this perspective, it is clear the so-called “trade war” was always going to be about more than just the exchange of goods and services. At issue is a strategic competition between the U.S. and China. Confrontations will occur, but thus far they have been conducted by means other than war. This contest will determine the direction of international affairs for the first half of the 21st century.

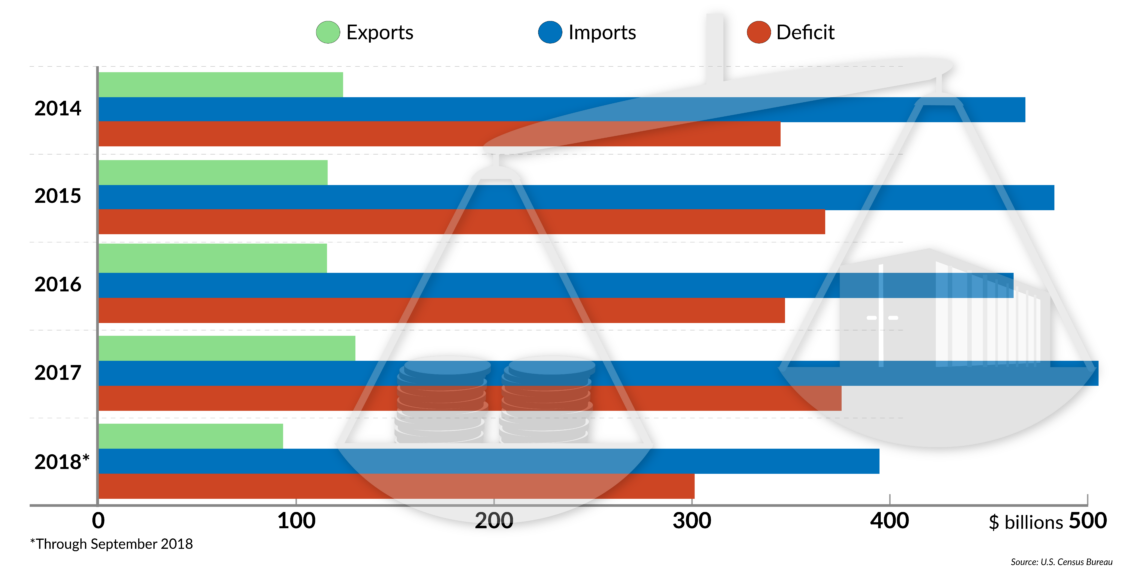

After the U.S.’s trade in goods with China reached a deficit of $375 billion in 2017, President Donald Trump’s White House slapped several rounds of tariffs on Chinese imports. In July it imposed tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods, in August $16 billion and in September a whopping $200 billion. The tariffs range from 10 to 20 percent, and could soon expand to cover the entire $505 billion worth of goods China sells to the U.S.

China has retaliated proportionately but in lesser measure, because its imports from the U.S. are worth only about $130 billion. Although consumers on both sides will ultimately be worse off due to higher prices and/or inferior goods, the U.S. has more leeway to levy tariffs on China because of the lopsided trade flows. In doing so, the U.S. has essentially undermined Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” growth strategy, which aims to increase the share of Chinese domestically produced core content in high-tech products to 70 percent in the next seven years.

Any trade war that lasts 20 years, of course, is no longer about trade and more about war.

As global attention was fixed on the trade posturing between Washington and Beijing, Alibaba Executive Chairman Jack Ma said publicly what many had suspected all along. On September 18, the self-made Chinese billionaire said the two giants’ trade war “could last 20 years.” Any trade war that lasts that long, of course, is no longer about trade and more about war.

Since then, a consensus has formed that the U.S.-China face-off is rooted in a strategic competition that was bound to happen. President Trump’s emphatic complaints about China’s theft of U.S. intellectual property and generally unfair trade practices have intensified. Most recently, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence referred to China’s use of “a whole-of-government approach” to “advance its influence and benefit its interests” in the U.S.

Broader confrontation

A larger struggle between the two grand competitors of the 21st century is unfolding, driven by opposing systems of socioeconomic organization, values and ideas about global order. China is effectively carrying on a battle of ideas and organizational systems in place of the defunct Soviet Union. If the second half of the 20th century was about the U.S. versus the USSR, between liberal democracy and market capitalism on the one hand and communist party rule and central planning on the other, then the first half of the 21st century is about the U.S. versus China.

The key difference is that China has blended communism with market capitalism. This Chinese adaptation of combining centralized control with a dynamic capitalist system, culminating under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, makes it a more formidable foe.

Despite appearing to forge ahead for a time in the 1950s, the USSR eventually lost to the U.S., imploding from within and disintegrating into states that we now see today in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The USSR was so powerful and fierce, equipped with immense human and natural resources, that even today its successor state, Russia, remains a force to be reckoned with and a major power in its own right. But Russia does not have China’s ability to match up to the size, reach and overall heft of the U.S.

Facts & figures

Trade imbalance

U.S. trade in goods with China

This is the broader context of the U.S.-China trade war. Trade disputes are not uncommon. The U.S. and the European Union (and its forerunner the European Community) have had trade friction for years, revolving around such thorny issues as agricultural subsidies. In past multilateral trade negotiations, particularly the Uruguay Round in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the U.S. and EU locked horns. Once they resolved their differences, the round was concluded. Smaller economies readily went along as they reaped gains from the deal.

The U.S. and Japan also had their trade disputes, especially in the 1980s. Books such as Who’s Bashing Whom?: Trade Conflict in High-Technology Industries and Trading Places: How We Are Giving Our Future to Japan & How to Reclaim It, headlined that era of anti-Japan sentiment in America.

The major difference is that the U.S. always found settlements with the Europeans and Japanese because they were allies. The U.S. helped rebuild Europe and Japan after World War II. Washington also provided nuclear deterrence and underwrote security for Western Europe through NATO, when the USSR and its Warsaw Pact allies were an existential threat. Japan still benefits from the American nuclear umbrella.

So when push came to shove, the Europeans and Japanese buckled, and the Americans restrained their own demands for fair trade. For example, after almost two decades of recording trade surpluses with the U.S., Japan agreed to revalue its currency vis-a-vis the U.S. dollar with the Plaza Accord in 1985. U.S. trade deficits with Japan narrowed, but the resulting asset price inflation worsened the bubble in Japan’s economy, which finally burst in the early 1990s. Nevertheless, the U.S.-Japan security alliance is still going strong.

Adversarial relationship

None of this applies to China. In its most recent National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy documents, the U.S. has officially labeled China a strategic “rival” along with Russia. But the Trump Administration has yet to treat Russia as a rival the way it has faced off against China. In fact, the U.S. appears to be treating China now not just as a rival, but as a full-fledged adversary.

Washington views China’s trade behavior and practices as exploitative and hypocritical.

As a senior White House official told me during a stopover in Bangkok after the Trump-Kim summit last June, Washington views China’s trade behavior and practices as exploitative and hypocritical. When China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 after 15 years of negotiations, the implicit bargain was that its membership in the body would lead to economic liberalization and reform. China was supposed to open up and join the international community like other countries where market capitalism led to political liberalization. Yet it did not.

In July 2018, at the World Peace Forum, China’s premier think-tank gathering, a senior Chinese government official gave a keynote address in which he conceded that China “cannot be as open” because it is still a developing country. It was a telling statement of how China sees itself. Outsiders may see the country as aggressive and ambitious, but the collective self-image at home is of modesty and pride, a nation still trying to find its way in the world.

These two firsthand accounts, whose basic assumptions are reinforced by the trade war, suggest the global economy is likely in for more headwinds. The U.S. sees itself as the aggrieved party, victimized for having constructed the postwar order only to see former outliers and junior partners achieve near-parity as competitors. The development and income gap between the U.S. and the rest of the world has never been so slim.

Hence the U.S., with the Trump administration’s preference for interests over values, is demanding “payback” in the form of trade concessions and burden sharing on a scale never done before. This mindset is behind Vice President Pence’s frustration that China is still following a state-led capitalist path, with a top-down, totalitarian, “whole-of-government” approach.

Scenarios

Even if a cease-fire in the trade war is reached, the U.S.-China showdown in the months ahead is likely to intensify. Beyond tariffs, the U.S. has defiantly demonstrated military force along the contested Taiwan Strait and in freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea. At home, U.S. authorities are rebuking China for intellectual property theft and cyber interference. Tensions have reached a point where there have even been proposals to expel some of the several hundred thousand Chinese now studying at American universities. It is not just the U.S. that is pushing back hard against China – Australia and, to a lesser extent, New Zealand are, too. A popular backlash against Chinese investment and influence is evident from Malaysia and Sri Lanka to Zambia.

Several major scenarios stem from this U.S.-China confrontation. The Trump administration is likely to keep up the economic, political and military pressure on China, so if the tensions are to ease, the onus is on the Chinese leadership. One potential outcome could be China conceding to American trade demands, biding its time until its economic and military strength more closely matches the U.S. But doing so involves domestic risks for President Xi, who cannot afford to appear weak at home. Since giving in to the U.S. may bring about his demise, the likelihood China will do so is low.

Yet standing up to the U.S. would incur more economic pain for China, as its supply chains shift elsewhere, resulting in lower growth. This outcome is also risky for China on the domestic front, as disenchantment may build against President Xi and his team. Such a scenario is therefore also unlikely.

With President Xi between a rock and a hard place, there is a remote chance that China could overreact, hastily taking extreme measures on the premise that it is being ganged up on by the U.S. and its allies. This is yet another scenario with a low probability, since it would mean more tension and probable conflict in hot spots like the South China Sea.

China has pragmatism in its DNA. If President Xi can find ways to manage domestic sentiment without rousing too much nationalism, we are more likely to see a give-and-take: concessions and compromises that will keep the U.S. on top for a while longer. The probability of this scenario is high, around 50-60 percent.