The EU and Turkey: Between confrontation and conciliation

Tension has marked recent relations between the EU and Turkey. President Erdogan has made conciliatory statements recently, but the question is whether anything can come of them. To avoid escalation, it will require levelheaded political leadership.

In a nutshell

- A bevy of issues divides Turkey and the EU

- Recent incidents have turned the situation volatile

- A levelheaded set of carrots and sticks could help

Tensions and verbal affronts have characterized relations between Ankara and certain European capitals recently, unsettling NATO and the European Union. These frictions arise from EU criticisms that Turkey is sliding toward authoritarianism, the de facto suspension of Turkey’s foundering EU membership talks and clashing interests around the Mediterranean Basin from Libya to Syria. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and French President Emmanuel Macron are locked in a personal vendetta, in the name of defending Islam on one side, and defending freedom of speech on the other.

Offshore energy discoveries

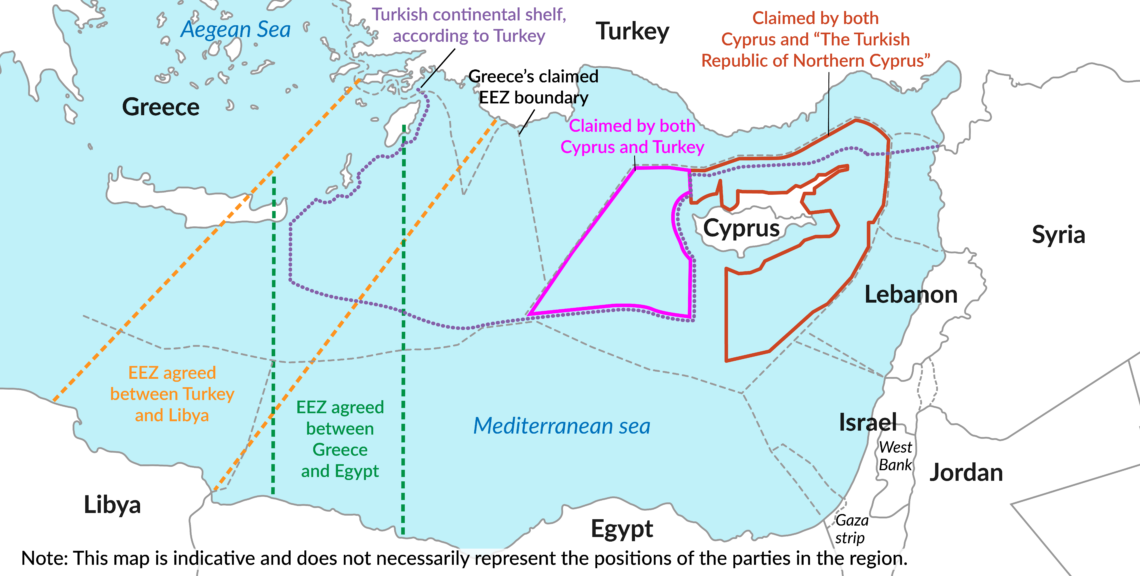

The discovery of offshore energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean has aggravated long-standing disputes between Turkey and Greece about the division of Cyprus and sovereignty in the Aegean Sea. Turkish warships, submarines and aircraft have escorted a research vessel into areas which, according to the prevailing interpretation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), fall under the jurisdiction of Greece and the Republic of Cyprus. Turkey did not sign UNCLOS because the convention entitles the many small Greek islands close to the Turkish coast to generate maritime zones on the same basis as other Greek territories.

Facts & figures

These islands, however small and remote from the Greek mainland, create a vast exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Eastern Mediterranean, providing rights to seabed resources, and block Turkey, with its long Eastern Mediterranean coastline, from establishing an economically significant EEZ there.

Last year, Ankara tried to break out of its coastal confinement by signing a maritime delimitation agreement with Libya, establishing a Turkish EEZ that overlapped the Greek zone. Athens countered by concluding a similar, overlapping agreement with Cairo. These developments, as well as disputes over Cyprus’s offshore drilling rights, ratcheted up tensions between Greece and Turkey.

Military involvement

Some European countries responded to Turkey’s naval intrusions into the Cypriot and Greek EEZs with a show of force. Cyprus, France, Greece and Italy conducted joint naval-air drills in the Eastern Mediterranean this summer. Air force planes from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), one of Turkey’s archrivals, joined Greek air force jets for exercises on Crete in September. For the first time, France joined another Turkish adversary, Egypt, as well as Cyprus, Greece and the UAE in the “Medusa” joint air-sea military exercises off the Egyptian coast in early December. Shortly afterward, Turkey announced firing exercises between the Greek islands of Rhodes and Kastellorizo, and near Crete.

The French president advocates using “all adequate means” to defend “European sovereignty” and international law in the Eastern Mediterranean. This stance has not yet produced constructive negotiations, but it has paid off in additional arms sales to France’s allies against Turkey.

In September, the sale of 18 French Rafale jets to Greece was announced, as were French moves to sell two state-of-the-art medium-size frigates to the Greek navy. Earlier, Cyprus signed contracts to purchase Mistral (surface-to-air) and Exocet (anti-ship) missiles from a French company, strengthening its limited air defense capability. Egypt and the UAE are major clients for French arms sales, despite objections from Human Rights Watch and other observers.

Disputes in the region have increased the risk of incidents at sea and escalation.

Earlier this year, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Italy, Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority formed the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) as a framework for energy cooperation. They have not responded to suggestions that Turkey be invited to EMGF meetings. Meanwhile, disputes in the region have increased the risk of incidents at sea that could escalate dangerously.

In light of these risks, Greek and Turkish representatives agreed in talks at NATO headquarters in Brussels to set up a bilateral mechanism to reduce the threat of military incidents in the Eastern Mediterranean. But this technical arrangement did not assuage EU concerns about continuing confrontation in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean.

A Turkish opening to Europe?

President Erdogan oscillates between moves that Western institutions perceive as provocations and hints of willingness to engage in constructive talks. Ankara appeared to offer an opening last month when the Turkish president declared that his country is an inseparable part of Europe and that all problems with European countries and institutions could be solved through politics, dialogue and negotiations. This soothing tone, albeit accompanied by affirmations of Turkey’s determination to defend its interests, aroused hope, momentarily, that the EU’s differences with Ankara could be addressed through mediation and compromise.

Hawkish gestures may be losing their allure.

But this declaration of attachment to Europe was short-lived and sprang as much from the Turkish president’s sense of vulnerability as from any desire to find an accommodation with Greece and Cyprus. The resignation of Turkey’s finance minister, Berat Albayrak, Mr. Erdogan’s son-in-law and chief contact person with the Trump family, as well as defections of senior figures from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), and the emergence of splinter parties, added to the president’s discomfort. In a rare show of unity, opposition parties called for early elections.

Foreign setbacks

Foreign setbacks increased President Erdogan’s unease. His tenuous rapprochement with Russian President Vladimir Putin has come under pressure following disagreements over Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. Because of Turkey’s purchase and testing of Russian S-400 missiles, the United States halted the delivery of 100 American F-35 stealth fighter jets and ended the involvement of Turkish firms in the production of the plane’s parts. In a further blow to Ankara, the first F-35s destined for Turkey were diverted instead to the American and Greek air forces. Disagreements with Egypt and Arab Gulf states, especially over Libya, as well as proxy conflicts with Iran, have further undermined President Erdogan’s aspirations to lead the Muslim world.

The Cyprus problem

Ersin Tatar, a hardliner, won the presidential election in the northern part of Cyprus in October with President Erdogan’s support, and seems likely to cede more control to Ankara. Following Mr. Tatar’s election, the Turkish president visited Varosha, a sealed-off beach resort in northern Cyprus from which Greek Cypriots fled after the Turkish invasion in 1974. The partial reopening of Varosha and Mr. Erdogan’s calls for a two-state solution to the division of Cyprus flouted UN Security Council resolutions that call for a comprehensive federal settlement.

In this scenario, Greece and Turkey agree to a joint scheme for exploration.

But hawkish gestures may be losing their allure. During President Erdogan’s visit, Turkish Cypriot demonstrators demanded a negotiated Cyprus settlement and mocked his “picnic” in Varosha. Wavering supporters at home, beset by economic turmoil, Covid-19, rising refugee numbers and increasing repression, are now less responsive to displays of nationalism. Yet Europeans worry that a vulnerable Mr. Erdogan may make perilous moves ahead of the 2023 presidential election, even going as far as annexing the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus,” which is recognized only by Turkey, and which is formally part of the territory of an EU country.

Scenarios

This volatile situation poses a dilemma for EU decision makers. Three scenarios can be envisaged for how the EU handles tensions with Turkey moving forward.

Under this scenario, the EU establishes clear red lines, in coordination with the incoming Biden administration in the U.S. and offers Turkey incentives to respect them – providing a more concrete, flexible and graduated version of the “positive agenda” that the EU tabled in October. This would entail the extension of Turkey’s 1995 customs union with the EU to additional areas, trade facilitation, education and youth programs, as well as cooperation on security, public health and migration.

The Turkish government has repeatedly called for negotiations and dialogue with Greece to address outstanding problems. The German foreign minister and the head of the British Secret Intelligence Service have held separate high-level talks sounding out Turkish openness to de-escalation and mediation. The Italian authorities are also interested in a possible role as mediator.

In this scenario, the chosen mediator succeeds in bringing the two sides together in a dialogue to seek a solution to maritime disputes and related issues. The mediator also succeeds in identifying confidence-building measures that keep the two sides engaged in the process. All parties refrain from provocative actions. Greece and Turkey agree to a joint scheme for exploration in contested waters.

As this conciliatory approach is consolidated, the UN launches a new effort to encourage Greek and Turkish Cypriots to reach a comprehensive settlement.

Under this scenario, the EU sets out its red lines and, as a warning, imposes limited sanctions on Turkish individuals and entities, in line with calls from the European Parliament. Ankara reacts by renewing exploration for oil and gas in Greek and Cypriot waters, including drilling operations, and again dispatches naval vessels to the zone. Member states aligned against Turkey reinforce their naval and air force presence in the Eastern Mediterranean. Greece presses for an arms embargo on Turkey.

In response to maritime incidents, the EU steps up its punitive measures, imposing additional targeted sanctions. President Macron, ruffled by repeated spats with his Turkish counterpart, calls for an end to the EU’s customs union with Turkey, the core of the two parties’ economic relations since 1995. In retaliation, President Erdogan announces the annexation of the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” and an end to cooperation with the EU on migration. The European Council decides on the formal termination of Turkey’s membership talks with the EU.

Ankara recalls its exploration vessel to port on the eve of each European Council discussion, hoping to put off any decisive EU action. In several inconclusive discussions, the European Council is unable to decide on red lines for Turkish domestic reforms and for its conduct in the Eastern Mediterranean. EU countries are divided between those advocating tough sanctions and an increased European military presence in the Eastern Mediterranean as a demonstration of serious intent, and those favoring further diplomatic efforts. EU-Turkish trade and routine cooperation proceed at a low level with no new initiatives.

Member countries are preoccupied with the Covid-19 recovery plan, unblocking the EU budget, responding to the blowback from Brexit and engaging with the new U.S. administration. EU-Turkey relations slip down the Council agenda, membership talks remain suspended but not formally terminated, incidents at sea continue and Washington expresses concern about conflict between NATO members. In the absence of EU action, the White House appoints an Eastern Mediterranean coordinator and the initiative for mediation passes to the American side.

Advocates of confrontation, led by France, are mostly playing to domestic opinion, knowing that their views will not mobilize a consensus in the European Council. Advocates of conciliation, led by Germany, wanting to keep the EU together, are aware that the parties in conflict are unlikely to respond to appeals for political negotiations, and instead urge restraint on a case-by-case basis. Drift, possibly with symbolic sanctions, is therefore the most likely short-term outcome.

In these circumstances, the risk of escalation will increase, with implications for NATO, the EU, the U.S. and regional powers. The question remains whether the incoming Biden administration, faced with overwhelming domestic priorities, as well as tensions with China and Russia, will have sufficient energy to push for a new transatlantic initiative and provide pathways back to regional stability.