Turkey winning ground in Central Asia

Russia’s influence in Central Asia could soon fade away entirely. After the boost in soft power following its intervention in Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkey could instead tap into cultural ties that would create a commonwealth of Turkic states close to Ankara.

In a nutshell

- Since 1991, post-Soviet Russia has retreated from Central Asia

- China has been wielding significant economic influence in the region for years

- In a new development, Turkey could strive to create a commonwealth of Turkic states

Much has been said on how the fragile “axis of convenience” between Russia and China could come unglued because of their unfolding rivalry for influence in Central Asia. But while that danger is still clear and present, the Kremlin has recently been given new and more tangible causes for concern because of a new competitor. The four Turkic-speaking Central Asian states could unite under Turkey’s leadership.

Civilizational states

In recent years, certain nations have begun presenting their culture as an alternative to Western “universal values” and rule-based global order. These “civilizational states,” like China and Russia, have developed narratives that depict their values as fundamentally different from, and superior to, that of the West. India’s Hindu nationalism follows the same approach, and so does Ankara’s pan-Turkism.

For Moscow, a budding pan-Turkic commonwealth would prove a painful reminder of its own unfulfilled ambitions.

The trend could signal the end of foreign and security policies driven by Western ideals. Soon, promoting democracy in faraway lands could go from being merely ineffectual to exacerbating civilizational conflict. If this comes to pass, Russia will be glad to see the West’s ambitions to sponsor regime change curtailed. However, it will be less pleased to have to compete with Turkey, which is so clearly bent on surfing the civilizational wave.

In the wake of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, where Turkey helped Azerbaijan crush Armenia, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan set his sights on a pan-Turkic commonwealth that includes Baku and most of Central Asia.

At the end of March, at a virtual meeting of the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States, President Erdogan argued in favor of formally upgrading the group to an international organization, citing its “significant international prestige.” The Turkic Council was established in 2009, and Turkey has not yet been successful in transforming it into a soft power tool. But this may be about to change.

Facts & figures

Pandemic permitting, the next summit of the Council will be held in Turkey this November. It will be the perfect opportunity for Ankara to present its achievements and to set ambitious new targets.

For Moscow, a budding pan-Turkic commonwealth would prove a painful reminder of its own unfulfilled ambitions. In 1991, the Kremlin created the Commonwealth of Independent States as a successor to the Soviet Union. The organization has been so ineffectual that few probably even noted that it met in Moscow in early April 2021. The creation of the Eurasian Customs Union in 2010, and then the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015, was less of a failure. But in addition to Russia and Belarus, the latter counts only Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia as members. Moldova, Uzbekistan, and Cuba are observers.

In addition to Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan all belong to the Turkic Council, with Hungary as an observer and potentially Ukraine as well. The main prize still up for grabs is the “permanently neutral” Turkmenistan, which holds massive energy reserves. Although courted by both Ankara and Moscow, a recent deal between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan on joint development of an oil field in the Caspian Sea suggests it may be leaning toward Turkey.

Russian retreat

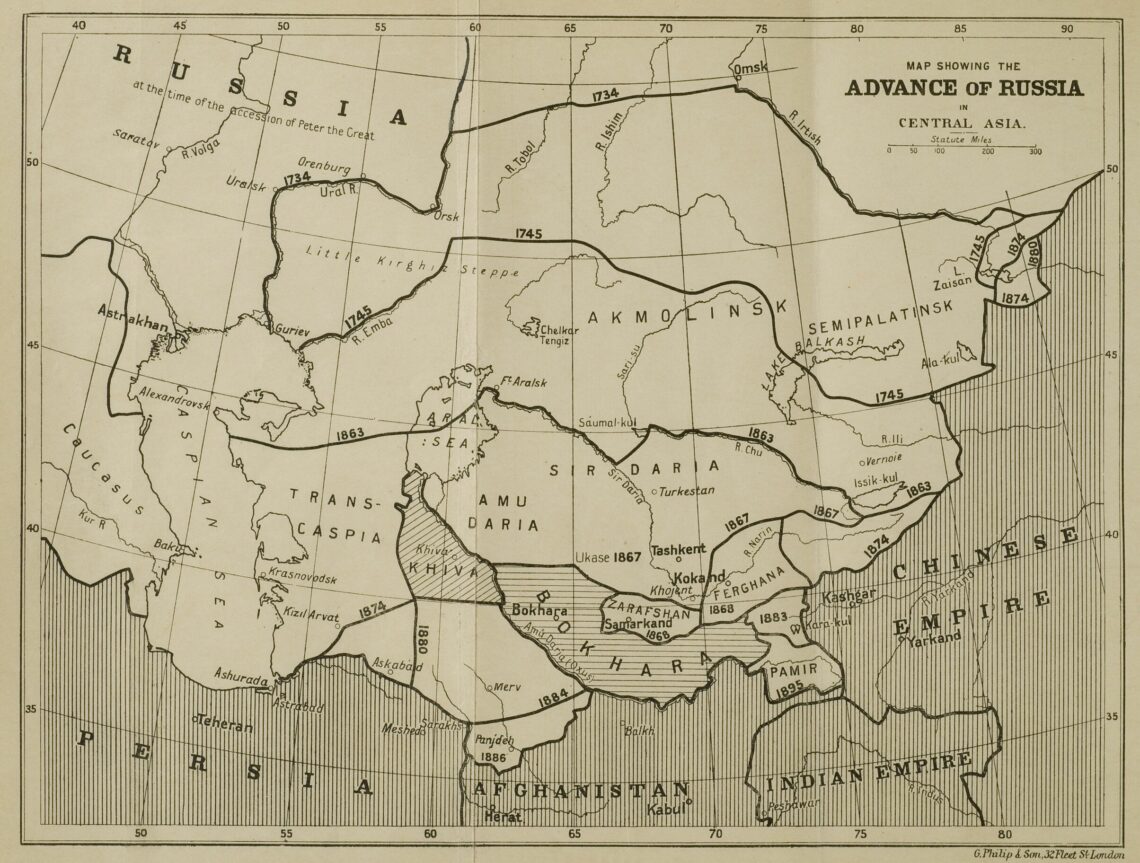

What should be of real concern to the Kremlin is its accelerating fall into geopolitical irrelevance. During the 19th century, Imperial Russia managed to keep the English and the Chinese at bay, establishing overlordship over what came to be known as Turkestan. Under communism, Moscow was in complete control of what then became known as Central Asia, ensuring that all vital transport infrastructure passed through Russia. But ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has been in retreat.

The main reason why Russia and China have managed to cohabitate in Central Asia is that Beijing has farmed out security to Russia while Moscow has accepted being eclipsed by China in trade and investment. But the Kremlin’s Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), far from being a success, is now under threat from Turkey.

In Central Asia, only Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are members of the CSTO, and in the South Caucasus only Armenia has joined. Following a trip in early March to Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu reported that non-aligned Uzbekistan had shown interest in Turkish defense equipment and that Tashkent is working with Turkish companies.

The Karabakh war showcased Turkish weapons, and exports to Central Asia are likely to increase as a result. To Moscow, the thought of Uzbekistan cooperating with Turkey and procuring NATO weaponry must be highly concerning.

Russia’s prior influence over the flow of energy out of Central Asia has been reduced.

The Kremlin’s prior influence over the flow of energy out of Central Asia has also been reduced. As late as 2007, it was still believed that modernizing old pipelines or building new ones would allow Russia to remain in control. Then China rapidly rolled out a network of pipelines that pump large volumes of both oil and gas eastward. And recent moves by Azerbaijan and Turkey suggest that their southern route into Europe is gaining in prominence. Any new pipelines out of the region will go south or west, not north.

Chinese advances

The real key to who will control the region is soft power, which boils down to a standoff between the major civilizational states. Russia is slowly but surely realizing that culture is the new currency of geopolitics. Beijing is already skillfully promoting the importance, if not the superiority, of Chinese culture. Russia’s response to the rollout of the massive Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will factor in the increasing role of this civilizational game. Russian observers have begun suggesting that to stay at least peripherally relevant, the Kremlin will have to start presenting its own culture as superior.

Although for now Russia can still bank on the military, economic and cultural influence it inherited from the Soviet Union, it will fade away with older generations. In deploying its own soft power, China has targeted younger Central Asians, perhaps allowing it to eventually cut Russia out of the picture altogether.

Already marginalized by China, Moscow must now face the rise of Turkish soft power in Central Asia.

In Central Asia, a growing number of Confucius Institutes teach Chinese as a second language. Chinese embassies have also targeted the education system, from primary schools to universities. They are donating school books, computers and other equipment to support a free Chinese-language curriculum.

Russia fears also having to compete with Turkey on the same front. Ankara may very well be successful. Much as they previously welcomed Chinese influence as a counterweight to Russia, Turkic states in Central Asia could now welcome Turkey as a counterweight to China.

Scenarios

The rise of Chinese influence has prompted a wave of Sinophobia. While the rollout of the BRI has brought large increases in trade and investment, it has also been associated with fiscal debt traps and Chinese labor. The Confucius Institutes have also served to monitor ethnic Muslim minorities like the Uighurs and promote the official Chinese narrative about Xinjiang – a part of historical Turkestan.

The other reason why Turkey could fare well in the region is that it combines its cultural offensive with economic incentives. It links in seamlessly with the BRI, offering access to southeast Europe. It aims to create a common market for goods, investment, labor, and services by 2028, and it has emerged as an attractive supplier of hi-tech weaponry. Its ambition to enhance the flow of trade along an east-west axis will also be supported by Western powers, as it cuts out Russia.

Of course, Russia cannot be discounted altogether. It still has a robust economic presence, and it will want to push back – as it did after the Turkish and Azerbaijani victory in the Karabakh war. It also has robust networks within military and civilian elites in several Central Asian states. And it could develop its ties with Iran, building rail links and organizing naval maneuvers in the Caspian Sea.

However, the writing is on the Kremlin wall. Already marginalized by China, Moscow must now face the rise of Turkish soft power in Central Asia. And despite all its troubles with Europe, Turkey is still in NATO.