Culture wars and real wars in U.S. foreign policy

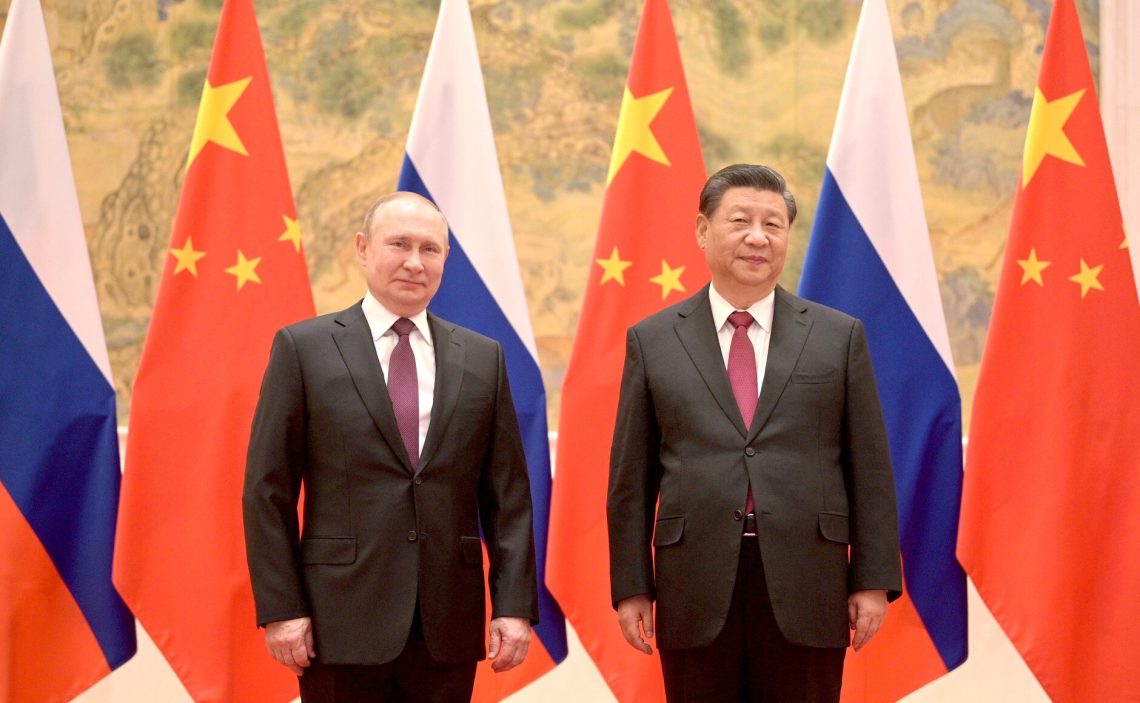

Foreign policy is becoming an extension of domestic politics. But adversaries like China, Russia and Iran are not likely to succeed in exploiting divisions in the United States or Europe.

In a nutshell

- “Woke” is now shorthand for culture wars across the United States

- Culture wars are swaying elections on both sides of the Atlantic

- Shared foreign policy interests will likely trump domestic disputes

The partisan divide in the politics of the United States has been exacerbated by cultural and social differences that may affect U.S. foreign policy. There are parallel debates erupting across Europe, suggesting that the transatlantic community might split along similar lines.

Without question, domestic issues are likely to affect political alignments in the U.S. and across the Atlantic as well as strengthen the hand of the parties in power. The divisions will probably not be significant enough to create geostrategic opportunities for adversarial nations like China, Russia and Iran to exploit.

What is ‘woke’?

“Woke” has become a code word for contrasting views on civilizational norms.

The social and cultural issues dividing America are broad and wide-ranging. They include race, gender, elections, immigration, class, crime, abortion, marriage, religion, education and parental rights. Controversies are widespread from local communities to the operation of federal agencies, including the armed forces.

“Wokeness in the military is being imposed by elected and appointed leaders in the White House, Congress, and the Pentagon who have little understanding of the purpose, character, traditions and requirements of the institution they are trying to change,” declared defense expert and retired U.S. Army General Thomas Spoehr, director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for National Defense.

Populists in the U.S. and Europe derided as fringe political movements a few years ago are winning elections.

“Being woke” started life in our postmodern world as vernacular for “alert to racial or social discrimination and injustice.” More recently in pop culture “woke” has morphed into a pejorative term. U.S. commentator Perry Bacon Jr. claims the term “woke” has rapidly come to encompass everything and anything conservatives don’t like – “anything and anyone they want to discredit.” Conservatives see it differently. “Many people now interpret woke to be a way to describe people who would rather silence their critics than listen to them,” according to Fox News commentator Michael Ruiz. “Woke” is now shorthand for culture wars across the United States.

This is more than just an American clash of ideas. The culture wars are increasingly part of the debate in the European sphere. For example, in Spain, the conservative party Vox has raised concerns over parental rights and gender issues, akin to those raised by U.S. conservatives in state elections in Virginia that brought a conservative governor to office.

In addition, pejorative terms for culture clashes are becoming part of the transatlantic discourse. In both the U.S. and Europe, for instance, elections that put conservative Giorgia Meloni in a position to lead the Italian government immediately led to charges that she was a “fascist.” The other side claimed such attacks arose from opposition to her party’s traditional views on marriage, family, gender and religion.

Electoral and political change

There is little question that the culture wars are swaying elections on both sides of the Atlantic. Populists in the U.S. and Europe derided as fringe political movements a few years ago are winning elections. More conservative leaders have come to power in Hungary, Italy, Poland, Sweden and the United Kingdom, partly because of shifting views over cultural and social norms.

In turn, the culture wars are sharpening political disputes. In the U.S., for instance, President Joe Biden, in a televised speech to the country, derided his political opposition as radical. In Europe, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen led a campaign arguing Hungary’s conservative government was undemocratic. She derided Ms. Meloni’s election and took part in talks to keep the conservative Vox party out of a possible coalition government in Spain.

Politics and foreign policy

The deepening partisan divide in U.S. politics is particularly noteworthy. The long-standing U.S. post-World War II truism that “politics stops at the water’s edge” is in tatters. As the two major political parties become more ideologically polarized, forging bipartisan political consensus is becoming more difficult. As a result, increasingly instead of politics stopping at the water’s edge, it is more the case that foreign policy is an extension of domestic politics. This trend is most clearly represented in climate policy, where the views of the two parties on global strategies mirror their domestic agenda.

The result of this increasing cultural warfare is that as it sways elections and delivers political power to one party or the other, increasingly that party’s political views will dominate the formulation of foreign policy.

This also has implications for international relations as the party in power will increasingly look to align across the Atlantic with like-minded regimes that share their approach to social and cultural norms.

Despite the “woke” wars and the exchange of jabs over who is a “threat to democracy,” U.S. and European polity has proven resilient.

It is, however, unlikely that cultural and political alignment will overturn traditional considerations of national interests. Indeed, where national interests are perceived as vital, that influence continues to preempt other concerns. U.S. support for NATO is a case in point. For instance, despite hyper-partisan disagreements, the measure to approve Sweden and Finland joining NATO garnered overwhelming bipartisan support. Further, U.S. support for Ukraine remains bipartisan and looks to continue despite the outcomes of the midterm national elections.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that foreign policy will yo-yo a good deal from administration to administration and from election to election, depending on which political party has its person in the White House. That said, political realignment is unlikely to impact the fundamentals of U.S. foreign policy. No matter which party wins, the U.S. will not ricochet between reflexively isolationist or globalist, but hover somewhere in between.

There will be less opportunity for adversarial powers like China, Russia, and Iran to exploit divisions over cultural and social norms than one might expect. For one, none of these regimes have demonstrated the ability to be exceedingly good at this. For another, despite the “woke” wars and the exchange of jabs over who is a “threat to democracy,” U.S. and European polity has proven resilient. Indeed, civil unrest in Iran, Russia, and China is exceeding any fragility in the West.

That said, the changes in the administration will affect transatlantic relations. Republican-led governments will lean more toward the UK, Nordic, Baltic, Central and Southern Europe, and remain more skeptical of partnering with the European Union. Conversely, Democratic regimes will work more comfortably with Paris, Brussels and Berlin.

A growing area of tension, regardless of which parties are in power, will be public-private partnerships, where conservative groups will react less favorably to environmental, social and governance (ESG) programs and diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives (DEI), while progressive governments embrace them. Corporate culture in both the U.S. and Europe is trending more progressive. This could result in a more turbulent and divisive transatlantic business environment, particularly as nations also grapple with increasingly difficult geostrategic issues like sanctioning Russia and Iran and decoupling from China.