War in Ukraine: Assessing the EU’s response

The European Union, as structured, cannot do a great deal more to aid current Ukrainian war efforts. Individual member states will continue to follow Washington’s lead.

In a nutshell

- European voices are increasingly concerned about a protracted war

- Direct EU support is limited by institutional design

- U.S. allies will back its continued support, with more or less enthusiasm

Every war is “an unnavigated sea full of cliffs,” warned Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831) in his oft-quoted book, “On War.” It would be presumptuous to attempt a prediction about the conflict in Ukraine that extends beyond a few weeks. More than a year after the Russian invasion, the Kremlin’s war aims remain opaque. One can only speculate about what President Vladimir Putin views as a realistic goal, and where he might be willing to make any concessions.

Moscow maintains escalation dominance: it has considerably more say over the time and scope of the hostilities, as well as their possible cessation. Addressing the United Nations Security Council in February, United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken described the situation as follows: “If Russia stops fighting and leaves Ukraine, the war ends. If Ukraine stops fighting, Ukraine ends.”

Defying expectations

Secretary Blinken was referring to the asymmetry between a state defending its sovereignty and territorial integrity, and a neighboring state waging a war of annihilation. The extremism of today’s “Great Russia” imperialism, on the one hand, is met with Kyiv’s reluctance to make territorial concessions under any land-for-peace formula or to restrict its right to choose its own allies.

This conflict, as its first year has shown, cannot be resolved by political or diplomatic means. Since victory for either side is out of the question in the foreseeable future, a cease-fire will not be a step toward ending the war, but merely a pause for each side to strengthen itself for the resumption of hostilities and mobilize further resources. Ukraine is threatened with a scenario similar to the “frozen” post-Soviet conflicts in Moldova (Transnistria) and Georgia (Ossetia and Abkhazia). However, given Ukraine’s strategic importance, it is unlikely that the conflict will permanently freeze. Rather, it will continue to simmer and flare up again and again. The front lines at the time of any cease-fire would turn into a de facto border.

At the beginning of last year, it was widely expected that Ukraine would not be able to withstand the pressure of the invasion indefinitely – and, later, that Russia would relent under the rising costs of its war of aggression. In fact, despite all the sanctions, Russia’s resources – not least due to the Moscow-Beijing partnership – seem robust enough to endure a long war, while high morale combined with Western arms supplies have enabled Ukraine to continue the fight against the invaders.

In the absence of a serious common foreign and security policy, the EU behaves as one would expect from a confederation of states.

Ukraine must necessarily accept dependence on Western support. As Mr. Blinken might have also put it: if the West stops supporting Ukraine, the war ends; if the war ends, Russia has won. Donor countries can influence Ukraine’s strategy by supplying weapons in a measured manner. They will support Ukraine only as long as Kyiv’s war aims (liberation of the entire Russian-occupied territory, including Crimea) are compatible with their interests. Individual allies have different concerns, as illustrated by the fact that a hesitant Germany handed over the first Leopard 2 tanks to the Ukrainian armed forces only one year after the beginning of the invasion.

In Europe, as well as in the U.S., there are more voices warning of the consequences of a protracted war. If Ukraine’s planned Spring offensive fails to prove that Western military aid continues to be worthwhile, Kyiv will be threatened with a gradual reduction in its volume, if not its end. Solidarity with Ukraine would weaken, and the inclination of Germany, France and other European Union countries toward “normalizing” relations with Russia would increase. This is especially true in countries where electoral politics feature populist parties that advocate a neutralist course and an end to military aid.

The European landscape

The model of the European neutralists is Hungary. During the war, a “reorganization of the power structure of Europe” is taking place, as Prime Minister Viktor Orban put it during a March event at the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Until now, Europe’s economic power has been based on cheap energy and raw materials from Russia, he argued; but now, “one dependence is slowly but surely being replaced by dependence in the other direction.” At the same time, the European center of power was said to be shifting from the German-French axis to a “new north-central European region,” with Poland at its heart – and also Ukraine (depending on “how much of Ukraine will remain”). In view of its energy dependence, Hungary wants to preserve as much of its relations with Russia as possible.

But Prime Minister Orban is an outsider among most European Union leaders, who see him as a pariah of the liberal world order. Like other EU countries, Hungary provided humanitarian aid to Ukraine from the outset, but refused to supply it with weapons and ammunition. It is none of his country’s business if two Slavic countries wage war against each other, Mr. Orban claimed in a February speech to the nation. Hungary only reluctantly agreed to the EU sanctions against Russia and finally to Finland’s admission to NATO. Mr. Orban will probably also agree to Sweden’s accession to the alliance, in consultation with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The timeline for this is currently still unclear. Hungary has cited Scandinavian criticism of the Hungarian legal system as the reason for the delayed approval.

Read more on the war in Ukraine

Would a Republican U.S. president support Ukraine?

At the other end of the European spectrum is the United Kingdom, which since Brexit has been more oriented toward the U.S. than before. The Biden administration leaves no doubt about its determination to continue supporting Ukraine. “For the first time since the end of World War II, the U.S. may once again become – in U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s words from 1940 – the ‘great arsenal of democracy,’” as described recently in Foreign Affairs magazine. For Washington, U.S. support for Ukraine bears heavily on its leading role in the Western alliance.

Between the Anglo-American “bellicists” and the continental “neutralists” are the mostly cautious old member states of the EU, which are oriented toward Germany and France. Another camp is the new post-communist member states, which want to prevent a Russian victory in Ukraine at all costs because it would endanger their own security. They see their closest ally in the U.S., not in Brussels.

Sources of support

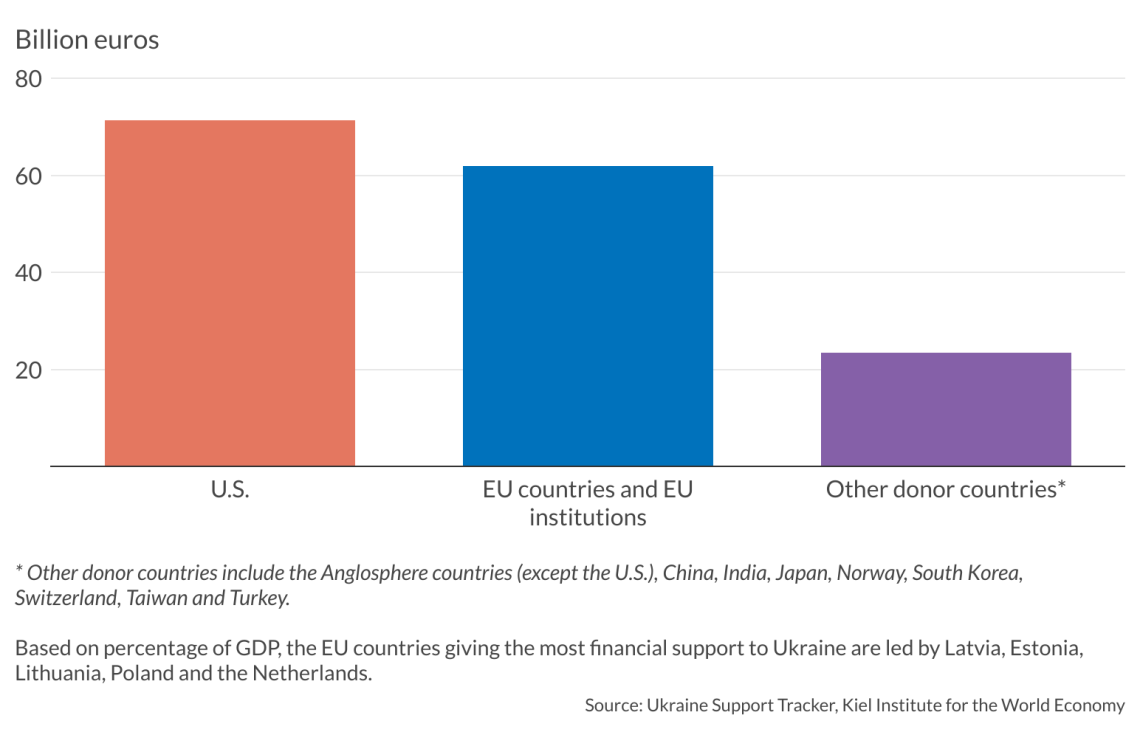

The Kiel Institute for the World Economy’s Ukraine Support Tracker estimates the total value of financial, humanitarian and military aid for Ukraine from January 2022 to January 2023 at a total of 143 billion euros. By far, the largest aid came from the U.S., at 73.18 billion euros, of which 44.34 billion euros was for arms and ammunition. In second place were the EU institutions and EU member states, which spent 54.92 billion euros. This is less than a tenth of the 570 billion euros allocated by the EU and EU countries to compensate for the strain on their businesses and households caused by the sharp rise in energy costs.

In November 2022, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell presented a first interim assessment: “At least 8 billion euros in military equipment have already been provided to Ukraine by the European Union and the Member States.” The European Defense Agency (EDA) was established in 2004 to facilitate the coordinated purchase, development, and use of military equipment. The need for such an initiative is shown by the example of battle tanks, of which the U.S. uses one primary type, compared to 12 in the EU.

Facts & figures

The EDA is currently negotiating contracts with arms companies for the supply of ammunition to Ukraine for 17 EU countries and Norway. However, it has been accused of proceeding too slowly and too bureaucratically. Germany is participating in the program, but also wants to open up arms industry contracts to outside partners. Denmark and the Netherlands were the first interested parties. According to the German Ministry of Defense, this approach is faster and less bureaucratic than via the EDA.

There are also other European institutions dealing with aid to Ukraine. The European Peace Facility has 3.1 billion euros at its disposal, intended to compensate member states for the costs they incur in supplying Ukraine with weapons. The EU’s Macro-Financial Assistance program provided Ukraine with 1.2 billion euros in the first months of the war, with funds already approved totaling 28.2 billion euros. Finally, in March, the European Investment Bank provided Kyiv with an emergency loan of 2 billion euros.

Scenarios

The EU itself cannot be accused of doing too little. In the absence of a serious common foreign and security policy, it behaves as one would expect from a confederation of states – trying to find a common denominator for the different interests of its member states, and to coordinate support measures as best it can. However, it remains the sovereign member states that decide on the extent and speed of those measures. And it is the U.S. that is urging its partners within the framework of NATO to accelerate and expand arms aid.

Under one scenario, as long as the U.S. continues its support and throws around its weight in NATO, the EU and beyond, the states in its orbit of influence will join along – albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Politically, attention will have to be paid to whether the German-French “coalition of the willing” can withstand domestic political pressures and cooperate with Washington.

Alternatively, dramatic changes on the war front that benefit Russian forces could create a completely new situation. While a Ukrainian military defeat is much less likely today than it was a year ago, it cannot be ruled out. In such a scenario, the Western pro-Ukraine alliance would quickly disintegrate. European countries would try to repair their relations with Russia as quickly as possible, inevitably taking into account the demands of the new Eastern European hegemon.