Ukraine’s other war

As Ukraine’s forces battle Russia, Kyiv’s political leaders need to battle corruption. One place to start is by creating a fair, simple and transparent tax system.

In a nutshell

- Ukraine’s corruption could derail postwar recovery and reconstruction

- A tax system that inspires trust and compliance will help economic growth

- Wartime sacrifices will hopefully spur societal demands for accountability

Ukraine is fighting a two-front war: one against an external enemy, Russia, and the other against an internal one, corruption. It needs to win both wars.

In January 2023, the Ukrainian government was hit by yet more financial corruption scandals, one involving a deputy minister of defense and another ensnaring a deputy minister of infrastructure. Countless more have preceded these cases. Just before Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy had finally started to embark on an anti-corruption drive, more than two years after his 2019 landslide election.

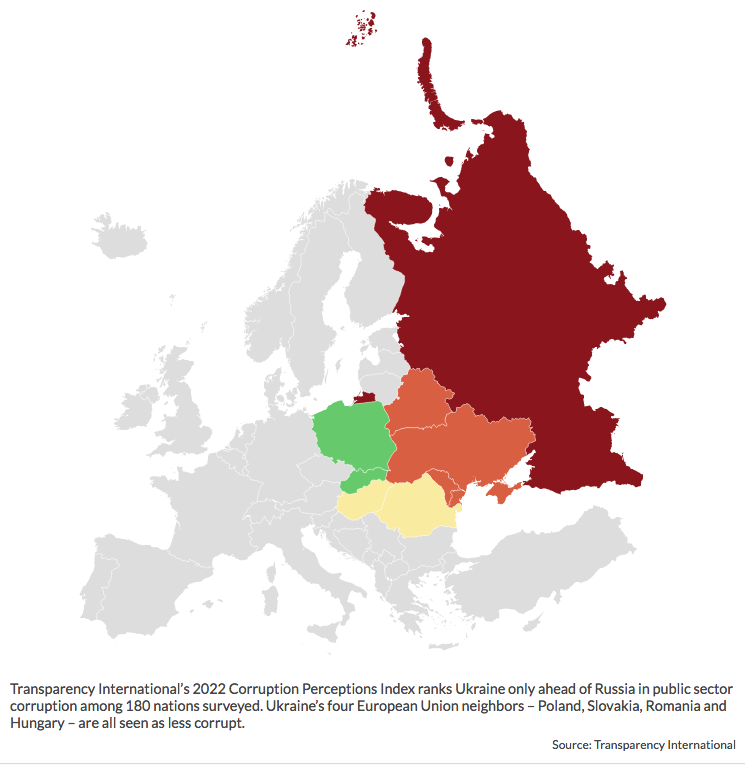

The challenge is daunting: Ukraine is among the most corrupt countries in Europe and toward the bottom globally. According to Transparency International, its 2022 Corruption Perception Index was still 33/100, ranking 116 out of 180 countries. The realities have prompted foreign investors to shy away, or in some cases run away, from a nation seen as a playground controlled by a handful of oligarchs.

Keeping corruption out of reconstruction

Such levels of corruption do not bode well for postwar reconstruction. Russian aggression has flattened many places, severely damaged infrastructure, disrupted economic activity and reduced the number of available men. Ukraine will start again from a much lower economic base than before the war.

On top of that, billions of euros and dollars are pouring into the country to support its war efforts against Russia’s invasion. Despite the obvious moral justification for such support, international aid has a track record of breeding inefficiency and corruption in countries with fragile institutions.

Reconstruction could thus be stunted or even derailed by corruption. Even as the war drags on, now is the time to address the issue. In March a conference organized by the Kyiv-based Institute for Economic Leadership in cooperation with President Zelenskiy’s office addressed some of the root causes. Supported by efforts of the United States-based Atlas Network’s Tom Palmer to gather international experts amid war, the event suggested solutions from an unusual angle: by looking at the country’s complex and corruption-incentivizing tax system.

Ukraine’s war effort is hobbled by spies, traitors – and corruption

Freedom for recovery

A more favorable business climate is essential if Ukraine is to reduce its dependence on foreign aid and subsidies – which part of its political class wants to do – and rely mainly on its own economic growth, based on the country’s ability to attract domestic and foreign investment. Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder – also known as the Miracle on the Rhine – led to the nation’s rapid reconstruction after World War II. A key element came in 1950, when the country decided to stop price controls. Ukraine also needs to free its economy today.

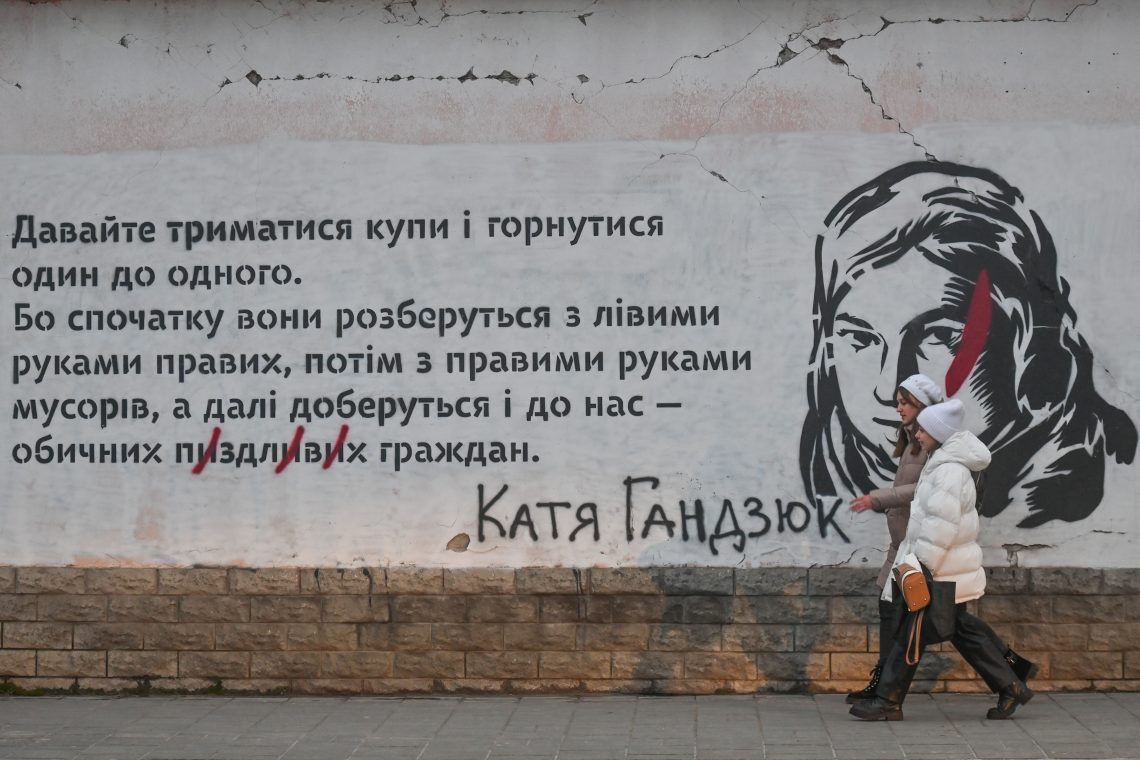

Ukrainians’ resilience is as astonishing as their bravery against aggression: businesses continue operating and President Zelenskiy has asked people to work, go to the restaurant and to “make money.” No doubt the shock of war has intensified not only the will to live but also the motivation to live in a society where there is equality before the law and greater intolerance for corruption.

What the country needs is more economic freedom. As the Fraser Institute, a Canadian-based think tank, puts it: “Individuals have economic freedom when the property they acquire without the use of force, fraud, or theft is protected from physical invasions by others and they are free to use, exchange or give their property as long as their actions do not violate the identical rights of others. Individuals are free to choose, trade, and cooperate with others, and compete as they see fit.”

Economic freedom is a crucial step toward prosperity. And lower, more transparent taxation is a big part of it.

Facts & figures

Laffer effect

The 1980 Reagan Revolution in the U.S. was partly based on economist Arthur Laffer’s famous bell curve on the economic effect of taxation. Its message was straightforward: past a certain level, taxation becomes counterproductive as higher rates generate less tax revenues for the government. The reason? Incentives to work and invest matter. With higher marginal tax rates, workers prefer to substitute work with leisure. Business tax rates that are too high disincentivize commerce. Indeed, many countries realized the importance of the Laffer effect and changed their tax system accordingly.

However, in poorer countries, people cannot afford not to work. They reduce official activity and do business “underground” for tax-avoidance reasons. And this is precisely the situation in Ukraine: businesses avoid paying taxes. According to a poll by the organizers of the conference, in June 2022, the most popular tax avoidance scheme in their respective sectors according to 68 percent of respondents was to pay salaries in cash. Thus, 30 percent declared paying only half of their salaries officially, and 21 paying only half of their due corporate tax. “Fake expenses” represented nearly 40 percent of answers.

It is no wonder that avoidance is so high, considering that a Ukrainian employer can pay 40 percent of an employee’s salary in taxes when combining an income tax of 18 percent and social taxes of 22 percent. A 1.5 percent military surcharge tax was also added in 2022. In the context of a relatively poor economy, these figures are comparatively quite high.

Some countries have implemented lower taxation, with successful results regarding tax revenues. Bulgaria lowered its rates at a flat 10 percent both for corporate and personal tax and Ireland increased its tax revenues by up to 50 percent after cutting its corporate rate by half in 2000-03. In Ukraine, too, the lesson from the Laffer effect could be implemented. More than half of respondents declare they would be willing to pay taxes officially if taxes were lower and 28 percent that they would increase their share of official salaries. Less than 2 percent actually declare they would still avoid paying taxes anyway. Just like in other countries that implemented radical tax reforms, tax revenues could increase.

Tax simplicity

Lower taxation is not the only piece of the puzzle. Simplicity and transparency also matter. Taxation is about trusting the government. In the context of a low-trust society and a low administration capacity, tax regimes are often suboptimal. They rely on economically less efficient taxes such as levies on turnover, trade or inputs. Those are precisely chosen to avoid tax evasion that more efficient taxes, such as profit tax, can more easily allow. As recalled by economist Simeon Djankov and Ukrainian member of parliament Maryan Zablotskyy, such is the case of Ukraine.

They also add that Ukraine’s tax regime creates distortions since the tax code is not respected in practice. Of course, there is the shadow economy: it is estimated that 42 percent of Ukrainian companies operate unofficially. But it gets even trickier: the unofficial practices of tax collection amount to direct negotiations between companies and tax authorities, giving the governmental representatives vast discretionary powers. Not only does this lead to “negotiated” lower effective tax rates, but it also opens the door to corruption. Mr. Djankov and Mr. Zablotskyy advocate a simplification of the system with a uniform rate.

When it comes to tax transparency, Estonia, once part of the Soviet Union, is probably the best example. For nine years it has been ranked as the best tax system by the U.S.-based Tax Foundation. The Baltic country, which introduced a flat tax in 1994 (but which has become slightly more progressive since 2018 with the introduction of new brackets) has a very transparent, predictable and easy-to-use tax system. No wonder it reduces the cost of paying taxes as well as economic inefficiencies, but also generates more civic trust – a precondition for a well-functioning democracy that will then manage its public spending wisely.

Scenarios

Scenarios depend on both internal and external inertias.

First, the war can crystalize a sense of national feeling of equality and accountability, and thus less tolerance for corruption and acceptance of reforms, but it can also trigger more corruption as recent scandals seem to confirm.

Second, inertia in the tax administration itself could prove an obstacle as old habits die hard, despite new incentives. Vested interests could slow down the reform process.

Third, given the level of international aid, foreign entities would probably have a say, or have some kind of lobbying leverage. Entities such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development are not big fans of flat tax or tax competition. International lending agencies also have an interest in maintaining some kind of dependence on them with public debt. Lower and more transparent taxes in Ukraine, however, must not contribute to growing public debt after the war. This is a part of the internal war in which Ukraine needs to prevail, just as it must defeat invading Russian forces.