Uzbekistan emerging from isolation

The rise of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev to power in Uzbekistan has brought economic reforms and new investments. The country desperately needs foreign partners to diversify its economy and strengthen its military. China and Russia, respectively, have stepped in to play these roles.

In a nutshell

- Uzbekistan’s new president quickly implemented economic reforms

- China has gained the most economic influence, offering billions in investment

- Russia retains significant sway due to military cooperation and cultural ties

- As the U.S. presence in the region wanes, Uzbekistan will carefully balance the two powers

Given its long track record of self-imposed isolation, Uzbekistan is an unlikely candidate for a success story. Recently, however, the country has received a lot of positive media coverage. It has received praise for its political stability and successful economic reforms, for striking multibillion-dollar deals with China, Russia and the United States, and for its foreign policy activism in Afghanistan.

There are good reasons to be skeptical. Landlocked in the middle of Central Asia, Uzbekistan does not border either Russia or China. Nor does it have access to the increasingly important Caspian Sea. Its long-sluggish economy is dominated by resources, mainly cotton but also gas and gold. Its security situation is marked by protracted conflicts with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan over borders that straddle the roads to China, and by the dangers inherent in sharing a frontier with Afghanistan.

The main impetus behind the current wave of positive news is the election of a new president. Following the death in September 2016 of Uzbekistan’s strongman President Islam Karimov, who had held power since 1989, many feared that a transition struggle could ensue, destabilizing the country and perhaps even leading to an Islamist takeover.

Economic reforms

The winner of the December 2016 presidential elections, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, quickly dispelled such fears. Having served as prime minister for 13 years, he was the ultimate insider. After early moves to consolidate his power, Mr. Mirziyoyev launched a bold program to extricate his country from the legacies of the Karimov era. In early 2017, he unveiled a national development strategy that focused on macroeconomic stability, free trade zones, enhanced competitiveness, agricultural development and a smaller role for the state.

The World Bank expressed satisfaction with the country’s ‘bold and ambitious reforms’.

By November 2018, there had been significant progress. The World Bank expressed satisfaction with the country’s “bold and ambitious reforms.” The country’s currency, the so‘m, had been removed from its peg to the U.S. dollar. In September 2017, the currency was devalued by 50 percent and in 2019 it will be made fully convertible. Ties with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), severed a decade ago, have also been reinstated, promising improved economic indicators and a better credit rating. This month, the country hired advisors for a debut sovereign Eurobond issue.

Looking forward, there are reasons for optimism. One positive legacy from the Karimov era is Uzbekistan’s low external debt – according to the World Bank, it averaged about 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) between 2006 and 2016. Due to increased borrowing in 2017, the debt ratio rose to a still very healthy 35 percent. With GDP per capita at $2,100 (on par with India’s and a quarter of Kazakhstan’s), the country is starting from a low base, giving it plenty of room for quick catch-up growth.

Potential dangers

That said, the caveats are numerous, ranging from endemic corruption and a shortage of human capital to a lack of established business networks. Most of all, however, Uzbekistan needs foreign partners and foreign markets to diversify its economy. The most obvious candidate here is China, which is not known for its benevolence.

Chinese interest in Uzbekistan has developed in two stages, beginning with a series of major deals on energy investments, such as the Central Asia-China gas pipeline, and culminating in President Xi Jinping’s announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The flagship of the latter program has been the 19.2-kilometer Kamchiq railway tunnel through the rugged Qurama mountains.

Built by the China Railway Tunnel Group Co., it is the longest railway tunnel in Central Asia and the first in Uzbekistan. Completed in February 2016, it was built in just 900 days (100 days ahead of schedule). Tenders by Western companies had suggested construction would take five years. The tunnel completes a key section of the Angren-Pap railway line, which connects Tashkent with the eastern Andijan region. Previously, travel by mountain roads between these two regions could take four to five days. Now the journey takes two hours.

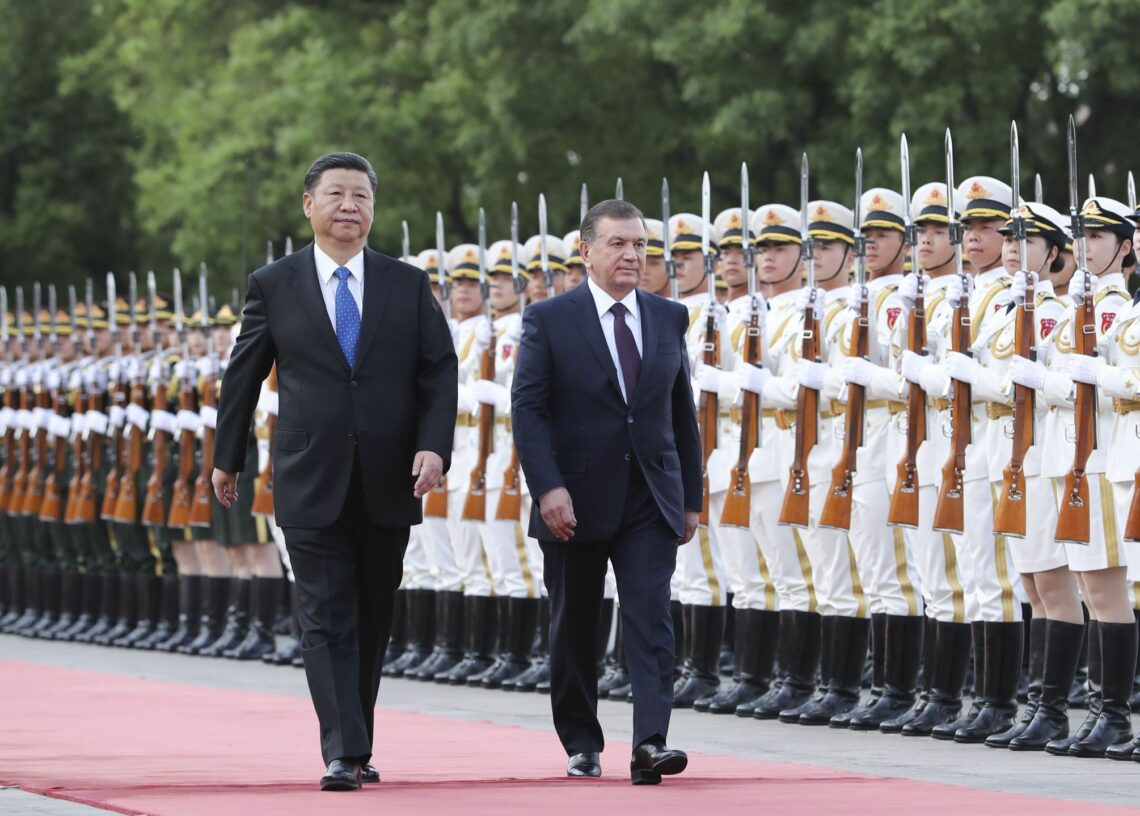

The Middle Kingdom has become Uzbekistan’s biggest foreign investor, and its ambitions for the future are running high. During a visit to China in May 2017, President Mirziyoyev landed $23 billion in investment contracts. At an October 2018 Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meeting in Tajikistan’s capital, Dushanbe, Uzbek Prime Minister Abdulla Aripov and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang agreed on broad cooperation in industry and energy, and on promoting the Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan-China railway, which could emerge as a serious rival to the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Mounting fears across the region of being caught in a Chinese “debt trap” could still thwart these plans. In sharp contrast to the European Union and the U.S., China offers loans and investment with no political strings attached. The downside is that Beijing’s predatory lending allows local leaders to accept large development loans that can prove hard to service.

Sri Lanka offers a case in point. Having accepted a major loan to develop the strategic port of Hambantota, the country was quickly overwhelmed by debt service costs; in July 2017, the port was taken over on a 99-year lease by China Merchant Port Holdings. Malaysia has asked China to cancel three infrastructure projects it cannot afford, lambasting Beijing’s “new colonialism.” Tajikistan has even ceded territory to pay off debt.

These experiences have created a window of opportunity for Russia to push back against growing Chinese influence, in what it still regards as its own backyard.

Russia returns

Having been displaced as energy hegemon in Central Asia, Russia insists it will retain its role as a security provider. Uzbekistan forms a key component in this ambition. Its population of 32 million is nearly twice that of Kazakhstan, and it has the largest military in the region.

During a visit to Tashkent in December 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced he would write off $865 million of Uzbekistan’s $890 million debt, making room for new loans to finance arms purchases. The obvious hope was that the country would rejoin the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which it had left in 2012. But President Karimov remained unimpressed, preferring to diversify his country’s defense relationships.

In January 2015, he announced that Uzbekistan would not be joining the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). At about the same time he accepted – as a donation from the U.S. – a consignment of 308 Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) armored vehicles worth about $300 million. In February that same year, China supplied eight medium- to long-range HQ-9 air defense systems which replaced outdated Russian S-200 surface-to-air missiles.

The death of President Karimov was followed by a substantial warming of relations with Russia.

The death of President Karimov was followed by a substantial warming of relations, entailing a visit by newly elected President Mirziyoyev to Moscow in April 2017. Economic concessions were offered to Uzbekistan that are normally only available to members of the EEU, such as an opening of Russian borders to Uzbekistan’s agricultural products.

Bilateral trade jumped by a third during 2017, reaching $3.7 billion, and grew by another 30 percent in 2018. Last year, a 12-year pause in military cooperation ended as the two sides held a joint exercise.

The warming of relations culminated in a state visit by President Putin in October 2018. He arrived in Tashkent at the head of a 1,000-person business delegation, the largest ever to visit the country. Headlines proclaimed that 785 business deals had been concluded, with a total value of $27 billion, outstripping the $23 billion negotiated with China the previous year.

The flagship item was an $11 billion agreement to build a nuclear power plant. Representing the first such venture in Central Asia, it will be financed by a soft loan from Russia and is expected to be completed in 2028. The first stage will involve two blocks with a combined capacity of 2.4 gigawatts, covering 20 percent of the country’s power needs.

When the plant comes online, it will free up domestic gas supplies for other purposes. Using gas turbines to produce an equivalent volume of power would require around 3.5 billion cubic meters of gas. That gas may now instead be used as feedstock for a petrochemical plant producing half a million tons of polymers.

The shopping list also included arms purchases, ranging from small arms to Su-30SM fighter aircraft. One deal included the sale of 12 Mi-35M helicopters. More is likely to follow, cementing Russian military influence

Common interests

President Putin’s visit also brought home that Russia retains an edge over China in language and cultural exchange, facilitating Russian connections with formal and informal power brokers. Building on this, President Putin brought with him 82 Russian university presidents. They concluded about 100 cooperation agreements with their Uzbek counterparts.

Perhaps the most important field of cooperation is a common interest in securing stability in Afghanistan. Given the oft-proclaimed Russian fears that a U.S. drawdown would lead to a Taliban resurgence, it has come as a surprise to many that Russia is (allegedly) supplying weapons to the Islamic fundamentalist organization.

The reason for Moscow’s support, however, is simple: The defeat of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh) in Iraq and Syria has caused its fighters to filter back into other regions. In Afghanistan, this has meant rivalry with the Taliban, recently exacerbated by al-Qaeda’s concern to show that rumors of its demise have been exaggerated.

The Kremlin has found it expedient to support the Taliban as the lesser evil, and Uzbekistan agrees. Hundreds of ISIS fighters are former members of the radical Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a terror group held responsible for some of the more horrific ISIS attacks in Afghanistan.

Following a visit by the Afghan president in 2017, and an offer by President Mirziyoyev to help broker peace in Afghanistan, in early August 2018 the Taliban arrived in Tashkent for four days of talks on subjects ranging from the withdrawal of international troops to Uzbek funding for key development projects, such as the 260-kilometer high-voltage power line from Surkhan, Uzbekistan to Puli Khumri, Afghanistan. The project would enable electrification of the railway from Hairatan, Afghanistan to Mazar-i-Sharif, at the border with Uzbekistan.

During his October 2018 visit to Tashkent, President Putin noted that “It is in our common interest to normalize the situation in Afghanistan.” In November, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov hosted the Taliban and the Afghan government for a conference in Moscow, bolstering the Kremlin’s credentials as an international peace broker after it took up the role in Syria.

U.S. presence fading

Meanwhile, the days of Western influence in Central Asia are numbered. It was significant that President Mirziyoyev’s visit to the U.S. in May 2018 resulted in no more than 20 business deals for a total of $4.8 billion – peanuts compared with those concluded by China and Russia.

Though it would be advantageous for the U.S. to take a more active role in Uzbekistan, this is not likely to happen.

While pundits make long lists of reasons why it would be advantageous for the U.S. to take a more active role in Uzbekistan, this is not likely to happen. The drawdown of troops in Afghanistan has reduced its interest in maintaining regional security, while encouraging investment from the private sector is problematic due to human rights concerns.

The outlook is also marred by the risk that Uzbekistan could fall into a “sanctions trap.” If Uzbek companies partner with Russian firms under sanctions, they run the risk of being targeted by secondary sanctions, pushing them into even deeper dependence on Russia. It must be remembered that most of the potential Russian partner companies for Uzbek firms are close to the Kremlin.

Although Russia may seem to have gained significant momentum in developing its relations with Uzbekistan, it lacks the economic muscle that China brings to the table. As one of my Russian colleagues said (with typically Russian cynicism): “What do you expect? We can offer millions. They offer billions!”

The outlook is that of a continued separation of roles, with Russia in charge of providing security and China providing finance. Seeking to balance his two main partners, President Mirziyoyev will remain wary of the downside of accepting Chinese credit and investment, and of getting too close to Russia. Domestic institutional reform may still free up some potential for economic development, but that is not an outcome on which one should bet too much.