Trying to end Venezuela’s never-ending crisis

The crisis in Venezuela deepens relentlessly. Negotiations between the desperate government of Nicolas Maduro and the opposition were interrupted. With international involvement, free and fair elections could occur, but before that happens, the question over President Maduro and his cronies will have to be resolved.

In a nutshell

- Venezuela’s deepening crisis shows no signs of abating

- Negotiations with the opposition have broken down

- The Maduro government is backed into a corner

Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis and the exodus from the country have become so bad that foreign observers have been convinced for months that they could not go on. But they do, month after month. Each report from the country, whether by journalists or foreign diplomats or representatives of international organizations, adds more detail to the record on Venezuelans’ suffering.

Data pours in on how many children are malnourished and how many people are dying of infectious diseases for which there are no drugs available. We hear how widespread and increasingly frequent are power outages in the cities. There are harrowing accounts about how the hospitals are frequently overwhelmed by patients who have no other access to healthcare.

At the same time, more and more people are leaving the country. According to United Nations estimates, more than four million people have fled the misery, rising crime and authoritarian repression – the government’s response to pressure that it cede power to the opposition. Although it seems incredible, there are now predictions that in the coming year that exodus could double. If that were to happen, it would mean more than a quarter of the country’s population will have left by the end of 2020. It is difficult to overstate the negative consequences of this exodus throughout South America. Absorbing that many refugees is a daunting task, as Europeans recently learned.

Presidents Maduro and Trump announced that the U.S. was in secret negotiations with members of Mr. Maduro’s inner circle.

Last month, the United States imposed another round of sanctions on members of President Nicolas Maduro’s government. Until that point, the most promising solution to the standoff between Mr. Maduro and the opposition, led by National Assembly President Juan Guaido, had been negotiations brokered by the Norwegian government. Oslo had convinced both sides to allow humanitarian aid into the country and had put new, supervised elections on the table for discussion.

Those negotiations were interrupted in August, when the U.S. announced a new round of sanctions, but were renewed in September with different participants. Then, on September 15, Mr. Guaido announced that the process had been “exhausted.” To confuse matters further, President Maduro countered by reaching out to some parts of the opposition that were not under Mr. Guaido’s control.

The sanctions regime was ratcheted up to an embargo on August 5, blocking all Venezuelan state assets in U.S. territory and threatening secondary sanctions against third parties trading with Venezuela. At the same time, President Donald Trump said he was considering a naval blockade to prevent any goods from entering or leaving Venezuela.

On the other hand, on August 23, Presidents Maduro and Trump both announced that the U.S. was in secret negotiations with members of Mr. Maduro’s inner circle. Diosdado Cabello, the head of the so-called Constituent Assembly, a pseudo-legislative body consisting exclusively of President Maduro’s supporters, was mentioned as the contact person. The U.S. has said that the talks were about how to get rid of Mr. Maduro. No one in Venezuela, however, has revealed their subject.

After President Trump fired John Bolton as his National Security Advisor, there was speculation that the U.S. would become more sympathetic to a negotiated solution to the Venezuelan drama. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, the former president of Chile whose report in July condemned the Maduro government for numerous violations of human rights, has urged all parties to support a negotiated settlement.

Meanwhile, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that Russia would stand with Venezuela and defend its right to independence and sovereignty. What that might entail has not been made clear.

Shrinking oil production

Aside from the Maduro government’s inability to ameliorate the humanitarian crisis, its central problem is its broad incompetence. The lifeblood of the government and the country is oil. More than 90 percent of the government’s revenue comes from the sale of petroleum. Following the purge over a decade ago of the national petroleum firm PVDSA’s technocratic leadership, the company is slowly dying.

Facts & figures

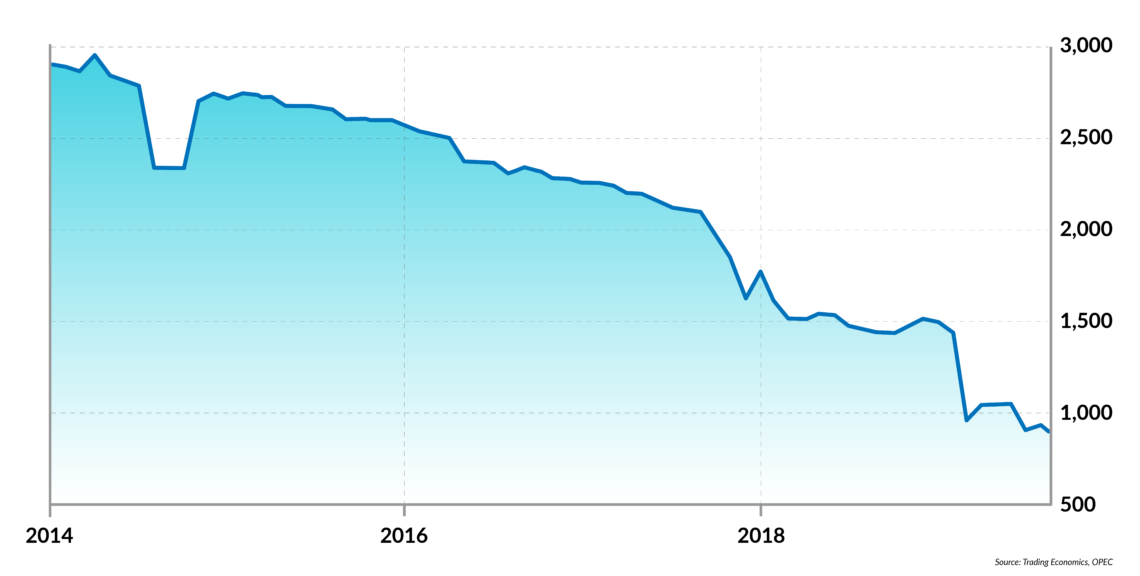

Venezuela oil production: 2014-2019

Thousands of barrels per day

Oil production has fallen below one million barrels per day (b/d) for the first time in 30 years. It currently stands at 800,000 b/d, half the output of just a year ago. Production is forecast to fall further, to below 500,000 b/d by next year. At that level, Venezuela cannot meet its obligations to China, its principal creditor; to Russia, which owns half of PDVSA’s U.S.-based cash cow, CITGO; or to any of its major customers. Over the past five years, the Venezuelan economy has shrunk by more than one half. Inflation is well above 1 million percent per year.

Through its inefficiency, the government is starving itself of hard currency, except what it earns through drug trafficking or other criminal enterprises. More immediately, half of PDVSA’s oil rigs are serviced by U.S.-based firms because the Venezuelan company does not have the expertise to manage them. Those U.S. firms continue to service the rigs under a waiver from the U.S. government that will expire in October. Under the new sanctions, it is unlikely that the U.S. Treasury will renew the exemption. In that case, the rigs would stop operating. There is a rumor that Chinese firms are prepared to step in to service the rigs. That leads us to the geopolitics.

Geopolitical factors

China is Venezuela’s principal creditor, holding just under half of the country’s sovereign debt. With a face value of about $60 billion, that debt has an open-market value of about 25 cents to the dollar. The Chinese have been unwilling to renegotiate the debt or step in to save the government with additional funds. Though they have an interest in propping up this weak and unreliable debtor, the Chinese want to avoid doing anything dramatic in support of Venezuela while they are engaged with Mr. Trump in an increasingly contentious dispute over trade and tariffs. There is no doubt that both sides in that debate are holding a Venezuela card that they will play if it becomes advantageous.

The Russians, who have spoken often and boldly in defense of the Maduro government, are in an even more vulnerable position. Russian oil firm Rosneft owns 49 percent of CITGO. Currently, this asset is tied in a series of court cases in the U.S. against the government of Venezuela. Canadian and American companies whose properties have been nationalized or rights otherwise violated are suing Venezuela for billions of dollars in compensation.

Venezuelan assets in the U.S. are an obvious target of creditors that have won cases in U.S. courts.

Just in the past few months, cases deciding more than $10 billion in claims have been handed down, with Venezuelan assets in the U.S. an obvious target of the winning creditors. If the U.S. government supports these claims in the new round of sanctions, Rosneft’s investment could be frozen or compromised. As if this were not enough, Russia also holds a chunk of Venezuelan sovereign debt, although it is a smaller share than China’s.

The new sanctions, which threaten third parties doing business with Venezuela, have hit India especially hard. Until this year, PDVSA was sending 300,000 b/d to India at favorable prices. The Indian government has told the Trump administration that it will cancel its contracts on condition that the U.S. can supply the oil it needs. With a soft international market for oil, even considering the recent attacks on Saudi oil facilities, the U.S. is more than willing to export some of its new shale production to India.

Until his death, former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez used the vast petroleum wealth his country produced as the largesse for an anti-U.S. alliance called ALBA. Specifically, he provided cheap oil to Cuba and Nicaragua, both regimes now on the U.S. blacklist. Cuba continues to get some fuel as it gives full value in return in the form of doctors, teachers and military intelligence support for Venezuela.

President Maduro does not dare end the shipments to Cuba because he cannot maintain his healthcare system, however underfunded it may be at the moment, nor can he keep his paramilitary groups or his intelligence apparatus without Cuban support. Ending the Cuban role in Venezuela is one of the Trump administration’s primary goals, given that its policy is driven by Republican Senator Marco Rubio and the Cuban-American lobby. In Mr. Trump’s opinion, the hardline policy guarantees him Florida’s electoral votes in the 2020 election.

Drug trade and the military

The final complicating piece in the Venezuelan puzzle is that President Maduro’s crowd is deeply involved in drug trafficking. Most of the cocaine moving out of South America to Europe now flows through Venezuela. That trade is making some Maduro loyalists (including, it is said, Diosdado Cabello, the interlocutor in the new secret talks with Washington) very rich. One bag man for the group was arrested in Florida with over $1 billion in money they wanted to launder.

Mr. Maduro and his close circle need assurance they will not be put in jail.

Since the military’s support is crucial to President Maduro’s power, most generals are either in the drug trade or have been given control over special import funds to bring in food and medicine. They have become rich using these dollars and selling a portion of the goods for their personal accounts. Junior and middle-rank officers fight for access to jobs in the economic sector so that they too can get rich.

This system makes the exit costs for Mr. Maduro and his close circle much higher than losing an election. This group does not need to negotiate a simple political transition. They need safe passage and the assurance they will not be put in jail when they leave Venezuela. The Trump administration’s Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams has hinted that this might be possible if President Maduro were to leave power voluntarily.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario, at least for the coming three to six months, is that the stalemate will continue. The disorder within the opposition and Washington’s unilateralism will help President Maduro hold on. Sooner or later (it will take months) the Norwegians, together with the Lima Group – 14 Latin American countries that are trying to push for a peaceful political transition without U.S. intervention, due to meet next in October – will get the negotiations started again. Those negotiations will go only in one direction: free, open and internationally supervised elections for the presidency.

President Maduro has offered to hold such elections within three months. The international community cannot organize elections in such a short time. The best solution for the opposition is a supervised campaign and elections in about six months. That supervision will be tricky, as the official UN report, prepared by Ms. Bachelet and her staff, has made plain. President Maduro, with Cuban support, can wreak havoc with an electoral campaign, as he did in the last national elections. How the international community can keep him from doing so again is the crux of the dilemma.

Less likely is that the Lima Group will offer Mr. Maduro and his closest cronies safe harbor somewhere and get him to leave with his booty, laundered or unlaundered. In that case, the elections can be held in a benign environment and the country can focus on a transition to democratic governance and set to the hard work of alleviating the humanitarian crisis.

One additional scenario, possible but unlikely, is that the Trump administration succeeds in forcing President Maduro and his cronies to flee, with their bags packed with greenbacks. How that will be orchestrated is unclear, but President Trump, with Senator Rubio at his back, has the military force to make it happen if he makes that decision. Such an intervention would infuriate the vast majority of governments in Latin America. That is a cost that President Trump may be willing to bear. For the moment, he is focused on other matters.