War in the North? Israel, Lebanon, Syria and Iran

Israel is girding for another war in southern Lebanon. But this time Hezbollah can pound northern and central Israel with up to 1,500 missiles a day – 10 times as many as it launched in the entire 2006 Lebanon war. And the conflict could well spread to Syria and Gaza, and perhaps even to Iraq and the Mediterranean offshore gas fields.

In a nutshell

- Both Hezbollah and Israel are far better armed than before the 2006 Lebanon War

- Neither want war, but the potential for an accidental confrontation is quite high

- Militarily, Israel must decide whether to fight a protracted, limited war or escalate

- Despite official Israeli denials, a preemptive strike cannot be wholly ruled out

At the end of February, the United States sent more than 2,500 air defense troops, including Marines and naval personnel, to Israel’s Hatzor Air Force Base, 40 kilometers south of Tel Aviv.

Their job was to practice joint operations with the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) in the event of a missile attack by regional foes, especially Iran and Hezbollah. “Once we get word, we can get here in days,” said Lt. General Richard M. Clark, commander of the U.S. Third Air Force, based at Ramstein Air Base, Germany. “I could be on the ground in one day. The fighting forces can be here within 72 hours.”

Similar joint drills have been held since 2001, but Juniper Cobra 18 was the biggest to date and almost twice the size of the previous exercise in 2016. This time, the troops seemed to be preparing for the real thing. Units were deployed to deal with “more accurate, precise, multidirectional fire” coming from the south, north or east, according to the head of the Israeli Air Defense Command, Brigadier General Zvika Haimovich. The U.S. Navy’s Aegis Combat System played an integral part in the exercise, as the USS Mount Whitney, a command and control ship, sailed to Haifa to provide additional guidance.

Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas went virtually unmentioned during the exercises, but the simulated battles left no doubt about the potential adversary. Both militaries got a chance to test out their first-line air defense weapons – for Israel, the Iron Dome, David’s Sling, Patriot and Arrow; and for the U.S., the Aegis, Patriot, TPY-2 radar and Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems. Most of the drills were computer simulations, but American Marines also practiced beach landings with IDF infantrymen, along with urban combat and tunnel fighting. Medical personnel from the two militaries also simulated a mass casualty event.

The Israeli defense establishment is more worried about Hezbollah than at any time since 2006.

Signs are accumulating that the Israeli defense establishment is more worried about Hezbollah than at any time since 2006. “The chances of war in 2018 are growing,” a senior IDF officer told Israel National News in late February. The question is what strategy to adopt when war comes, which depends on how one defines the objective. “If we succeed in eliminating Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, this will be a deciding factor,” the officer said.

Even if one doubts whether bumping off Mr. Nasrallah would amount to a meaningful victory for Israel, there is no mistaking the IDF’s deep concern. The army’s chief of staff, Lieutenant General Gadi Eizenkot, who is scheduled to step down at the end of this year, told a newspaper interviewer at the end of March that “it is possible that I shall have to command our army in war.”

New menace

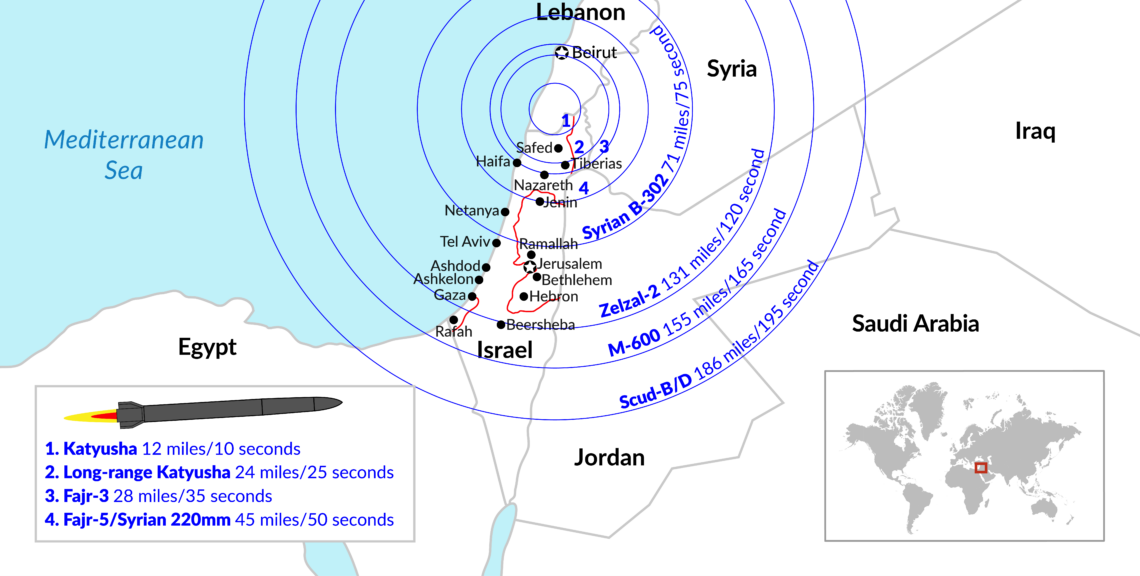

The war, if it comes, will be different. Israel no longer faces the threat of World War II-style mass assaults by enemy armored divisions and air forces, as was the case from the 1940s through the 1970s. Yet the 150,000 rockets and missiles deployed by Hezbollah in southern and central Lebanon are menacing in their own way.

To this total, we should add the Syrian government’s arsenal of surface-to-surface missiles. An aerial barrage of this scale – even if the projectiles are not very accurate – would probably overwhelm even the most sophisticated defenses and reach central Israel and perhaps farther south.

According to an assessment by the IDF’s chief of operations, Major General Nitzan Alon, Israel could be hit by between 1,000 and 1,500 rockets daily in the next conflict. This is ten times bigger than Hezbollah’s bombardment in 2006. A recent exercise by Israel’s Northern Command assumed this would result in approximately 130 civilian deaths and 400 wounded. While the exercise did not deal with infrastructure, one could expect attacks on key installations such as Ben Gurion International Airport and freight terminals – perhaps involving brief paralysis or interruptions of service.

Neither Israel nor Hezbollah want an armed conflict, yet there are many reasons why one could erupt.

On the other side of the ledger, Israeli capabilities have also improved. The IDF’s target attack capability is seven times better than in 2006, according to General Eizenkot, while ground troop maneuverability is also far better.

Flash points

Neither Israel nor Hezbollah and the Lebanese government have given any indication of wishing to break the cease-fire. And yet there are quite a few reasons why an armed conflict could erupt. Its scope could extend beyond southern Lebanon to involve Syria and the Iranian bases there, the Hamas forces in Gaza, and possibly Iraq as well. For this reason, Israeli Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman and some Israeli generals have referred to this possible confrontation as “the Northern War.”

First, Hezbollah is prodding the Lebanese government over three unresolved territorial disputes with Israel. One involves a border wall the IDF is building between the two countries. Another is the Shebaa Farms, a strip of territory seven miles long and two miles wide along the southwestern slope of Mt. Hermon. The third concerns offshore oil and gas drilling rights to the southern portion of Block 9, which Lebanon sold to an international consortium in December 2017. Minister Lieberman denounced the tender as “provocative,” while Hezbollah’s Hassan Nasrallah responded that any attempt to harm gas and oil platforms in Lebanese economic waters would bring reprisals against Israeli installations. U.S. attempts to mediate the dispute continue but have so far been fruitless.

There are also purely military considerations of an even more pressing nature. At the Munich Security Conference in February, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned that Iran is trying to build a factory in Lebanon to assemble “precision-guided missiles” with an accuracy of 10 meters. He said Israel could not allow the facility to be completed. Likewise, Iran would not be permitted to establish military bases in Syria, and certainly not south of Damascus.

The latter objective has sometimes been expressed vaguely enough to leave some doubt about what Israel would do if the Iranians set up large military facilities in more remote parts of Syria. (Although the mysterious predawn attack on Syria’s largest air base near Homs, also used by Iran, on April 9 seems to clarify this issue.) But the IDF already has clearance to attack convoys and logistical centers anywhere in the country involved in delivering sophisticated Iranian weapons – mainly long-range guided missiles – to Hezbollah. Israel has made it quite clear that the export or manufacture of such munitions in Lebanon will be regarded as a red line – and underlined the message with several bombing attacks over the past few years.

Accidental confrontation

The problem with enforcing these red lines is twofold. First, over Lebanon, Israeli jets are operating uncomfortably close to Russia’s Khmeimin air base near the Syrian port of Latakia. The Russian air defense radars allow them to track Israeli aircraft over long distances, even while they are forming up over northern Israel, and there is every reason to believe this information is passed on to the Syrians. In the days of the USSR, the Russians were in the habit of keeping their own advisors on the ground with the Syrian ground-to-air missile batteries, and that still seems to be the case today.

Consequently, any suppression of Syrian air defenses risks hitting Russian personnel. In a recent speech, Russian President Vladimir Putin warned Israel against just this possibility. While the IDF will take care to avoid any incidents, an accidental confrontation cannot be ruled out. There is also the possibility of a Russian radar locking on to an Israeli aircraft or a close encounter between Israeli and Russian warplanes.

Israel is adamant about its red lines, while Iran is equally determined to keep pushing the envelope.

No less risky are the repeated Israeli air strikes in Syria, although these attacks are usually at Hezbollah or Iranian targets. Even so, they are a challenge to President Bashar al-Assad’s prestige. Most dangerous was a direct exchange of fire on February 10, 2018, when Israeli jets struck at Syria’s air defense system – including its main command center and at least three missile batteries – after an F-16 fighter was downed by ground-to-air missiles. The incident started when an Iranian drone was discovered and shot down over Israel after taking off from a Syrian airbase.

This neatly shows the trigger mechanism for a major confrontation. Israel is adamant about its red lines, which it sees as existential. Iran is equally determined to keep pushing the envelope, as part of its effort to create a strategic sphere of influence stretching from Baghdad to Beirut. The danger of retaliation and escalation is greater from the Syrian side, too, now that Israel’s government has publicly disclosed its 2007 operation to destroy the Iranian-funded and North Korean-built nuclear reactor at Deir Ezzor. Mr. Assad’s finely honed sense of honor is being tested as never before.

‘Everything scenario’

A key question is how far the conflict could spread. Previous confrontations have generally been contained to a limited area, such as Lebanon in 2006 or 2014, or Syria in February 2018. But any serious fighting in Syria must inevitably involve Iranian personnel and pro-Iranian militias, including Iraqi formations. Two senior commanders of Iraqi militias were recently spotted on the Lebanese-Israeli border, and later made a public announcement pledging their support for Hezbollah in case of war. That declaration may well have upset Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, but even though his government is paying the militias’ salaries and providing much of their equipment, most answer only to Tehran.

In military exercises, the Israeli general staff often challenges its commanders with a worst case called “mikreh hakol,” or the “everything scenario.” While it is always possible that a confrontation will be limited to Lebanon or Syria, the greater probability is that it will spread quickly if it achieves a critical mass. That means Hezbollah, the Lebanese army, Syrian forces, Iraqi and Afghan militias, Hamas in the Gaza Strip, and perhaps even Palestinian Arabs on the West Bank and inside Israel might join the fray.

Of Hezbollah’s 150,000 rockets and missiles, only a few thousand can reach deep into central Israel. That makes the first day or two of fighting crucial, as each side does its utmost to inflict a knockout blow. The Israeli air force and long-range artillery will go all-out to destroy Hezbollah’s limited stock of long-range missiles before they can be used. As in 2006, Hezbollah will start by lobbing vast numbers of inaccurate, short-range rockets at large civilian targets close to the border, including the city of Haifa. The idea will be to kill as many civilians as possible and cause panic.

Managing missiles

Hezbollah will be highly selective in its use of long-range missiles, however. Mainly, they will be targeted at Israel’s air and naval bases. Given sufficient time and opportunity, the organization’s military arm may also hope to hit the IDF General Staff headquarters and Ben Gurion International Airport in Tel Aviv (which Hamas managed to close down briefly in 2014), along with other parts of Israel’s strategic infrastructure.

One tempting target would be industrial plants that process toxic materials. For several years, Hezbollah leader Nasrallah suggested that a 12,000-ton ammonia storage tank operated by Haifa Chemicals Ltd. would be a suitable target. (Following a final court order in May 2017, the facility near downtown Haifa has been emptied.) Hezbollah’s main hope is that after a day or two of intensive bombardment, the Israeli air defense will run out of missiles. Mr. Nasrallah has also promised that his followers will seize Israeli kibbutzim and other agricultural settlements close to the Lebanese border, and the IDF is taking this threat seriously.

Experience shows that after the traumatic mass casualties of the Iraq-Iran War, Iranians prefer to fight to the last Arab.

Syrian involvement would bring in more surface-to-surface missiles. But even if Iranian targets are hit in Syria, it is unlikely that Iran will get involved directly. Experience shows that after the traumatic mass casualties of the Iraq-Iran War, Iranians prefer to fight to the last Arab. Still, if Tehran decides to jump in, it possesses the Middle East’s biggest arsenal of medium-range ballistic missiles, including several types (such as the Shahab-3 and solid-fuel Sejil series) that can reach Israel. The Syrian and Iranian air forces do not pose a significant military threat, but suicide missions are possible.

Israel’s dilemmas

This type of conflict presents Israel with several strategic dilemmas.

One regards the rules of engagement. To avoid outraging the international community, Israel could react with restraint even if Hezbollah launches a 2006-style total war, with deliberate bombardment of civilian populations. Such a “proportionate” response would stick to precision strikes against military targets. Human rights organizations and many governments would still be unhappy, but the international fallout could be acceptable. However, success is far from guaranteed given Hezbollah’s tactic of embedding military targets in residential areas of Beirut’s Dahiyeh district and in the Shia villages of southern Lebanon. It is virtually impossible to hit the rockets without killing civilians as well.

Such strictly limited fighting would also likely mean a very long war. The Israeli air force cannot be expected to take out all or even most of Hezbollah’s missile batteries, allowing the organization to sustain a protracted campaign without absorbing too much punishment. But the psychological and physical damage to Israel would be intolerable. Recently, three senior Israeli officials hinted that a more aggressive strategy is being contemplated.

Defense Minister Lieberman has warned that if civilians in Tel Aviv are forced to stay in shelters, so will civilians in Beirut. Brigadier General Ronen Manelis, the IDF spokesman, issued an even clearer warning to the Lebanese on January 28: “Beware of Iran’s game using Hezbollah to gamble on your security and your future. The choice is yours.” In mid-March, he added that one out of every three houses in southern Lebanon is a command post or weapons cache, and Israel “will know how to attack them.” He also mentioned the missile factories and “terror tourism” that Hezbollah is organizing on the Israeli border for Iraqi Shia militia commanders, saying they represent a “real and present danger to Lebanon and the region.”

The next step up the escalation ladder would be for the IDF to take out Lebanon’s key infrastructure.

The IDF chief of staff, General Eizenkot, was even more blunt in a March 30 interview with the Israeli daily Yedioth Aharonot:

Hezbollah will be punished all over Lebanon, especially in Beirut … There are Hezbollah positions in 240 Shia cities, towns and villages, and you can expect much destruction there. Everything that serves Hezbollah will be flattened. We will take down the high-rise buildings in Beirut where Hezbollah is sitting. This will be a picture of devastation that no one in the region will forget … Civilian neighborhoods will not have immunity.

Just how far Israel is prepared to go when it comes to civilian infrastructure is another question. Due to domestic political inhibitions and foreign policy considerations, premeditated carpet bombing of civilian areas in the World War II style of London, Berlin, Dresden or Tokyo is out of the question. Even if Israeli pilots were given such orders (and there is no chance of that happening) they would refuse to obey them. However, the IDF will certainly destroy Hezbollah positions in Beirut and southern Lebanon, no matter how hard it tries to limit civilian casualties.

Targeting Lebanon

The next step on the escalation ladder would be to take out Lebanon’s key infrastructure. If this happens, it would represent a quantum leap. The target list would include bridges, the power grid, civilian harbors, airports and the transport facilities all over Lebanon. This strategy has never been adopted by the government and the IDF, but is being advocated in the Israeli media by several independent analysts, of whom perhaps the most authoritative is the former head of Israel’s National Security Council, retired Major General Giora Eiland:

If the fire from Lebanon continues and we decide this calls for a broad Israeli response, it should be a declared war against Lebanon. Fortunately, no one wants to see Lebanon destroyed – neither Syria nor Iran nor Saudi Arabia, the United States and France, who have invested a lot in the country’s infrastructure. … The threat to destroy Lebanon will lead to a cease-fire within three days, rather than 33 days [as in the 2006 war].

More recently, Israeli Intelligence Minister Yisrael Katz said that all Lebanon would be a target if Hezbollah fired on Israel. Apparently, Mr. Katz based his suggestions on President Michel Aoun’s declaration that Hezbollah must arm itself to complement the Lebanese army’s ability to deal with Israel. In other words, as President Aoun sees it, Hezbollah has the same status as the Lebanese armed forces, and therefore its actions represent the state.

If Israel declares Lebanon and Hezbollah as one entity even before war breaks out, this would infuriate the international community, but also prepare it for a conflict in which all of Lebanon is a legitimate target. In the 2006 Lebanese war, the Israelis did not go that far. They destroyed a few bridges in southern Lebanon but went no further. In a new war where Hezbollah launches 10 times more rockets, Israel may decide that escalation into strategic bombing (of Syria, too, if it gets involved) makes sense, if only because it is the fastest way to end the war.

That might explain the oblique references to Lebanon’s responsibility by the IDF’s spokesman, General Manellis, and Ministers Katz and Lieberman. Besides preparing global public opinion, the warnings could also deter Israel’s neighbors by indicating the high price of starting a war.

Invasion and Iran

Israel’s other big strategic dilemma is whether to involve the IDF in a ground war against Hezbollah in southern Lebanon. Hezbollah hopes Israel will be deterred by a combination of difficult terrain and sophisticated anti-tank missiles.

However, according to Israeli military analyst Alex Fishman’s interpretation of Minister Lieberman’s comments, Israel might still decide on a land invasion to breach the “wall of fire” that Iran and Hezbollah have erected along its northern borders. In the 2006 war, thanks to Israeli caution and the clumsy deployment of ground troops, Hezbollah kept launching its rockets until the last minute of the war. General Eizenkot’s comments on the improved maneuverability of IDF units may also indicate the intention to send in ground troops.

Israel must also consider whether to spare Iran if fighting erupts with its militia proxies and Iranian forces based in Syria. Assuming that Iran is ready to fight Israel until the last Shia Arab and Afghan, should Israel allow the Iranians to get away with it?

Attack or wait?

Lastly, Israel must make a strategic decision. Will it land the first blow or wait for its neighbors to strike? The history of the country’s wars shows an almost even split between these two options. A preemptive strike was chosen in October 1956, June 1967 and June 1982 – but Israel waited to be attacked in November 1947, May 1948, October 1973 and July 2006.

The main argument for Israel to attack first is that the inventory of advanced missiles in Lebanon and Syria is growing, despite the IDF’s efforts. This situation will get much worse if Hezbollah manages to complete Iranian missile factories in Lebanon. Furthermore, Iran will likely become a nuclear power within the next decade. It will then be able to hang a nuclear Damocles Sword over Israel’s head, with the aim of preventing any strategic move against Hezbollah. Before the 2006 war, Israeli generals believed that Hezbollah could be effectively deterred, allowing its thousands of rockets and missiles “to rust in their positions.” As it happened, they did not rust.

For now, a first strike does not seem imminent, but the Israelis may change their minds.

For now, a first strike does not seem imminent. “We are making an effort to keep the next war as far off as possible,” is how IDF spokesman Ronen Manelis put it in mid-March. General Eizenkot recently expressed hope that the cease-fire could last “for the next 30 years.” Yet, the Israelis may change their minds. At the very least, it seems they are keeping their options open in case the situation becomes unacceptably risky.

Thus, at the Herzliya Forum in June 2017, the Israeli air force commander, Major General Amir Eshel, explained that “a preventive strike at the [missile] factories … will decrease Hezbollah’s ability to launch [missiles] by 50 percent. … But such a decision will set the whole region on fire, and this needs to be taken into consideration.”

This was a strange disclosure. Presumably, he was thinking of a preventive strike against Hezbollah’s missile batteries, not just the factories. Otherwise, how would half the missiles already deployed be destroyed? But General Eshel did not elaborate.

The Israeli government’s official position is that it is determined to avoid war unless Israel is attacked first. But a few months or years from now, when the long-range precision missiles in Lebanon and Syria become an existential threat, this policy may be questioned. Hezbollah and Iran are not interested in war now, either, but once they are stronger, their calculations may be different.

Finally, what about Gaza and the West Bank? On March 30 of every year since 1976, the Palestinian Arabs of Israel have demonstrated against land confiscations by the state. Since 2001, these Land Day protests have spread to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, too. The anniversary of Israel’s founding on May 15 has also been the subject of very widespread demonstrations. If, during such domestic unrest, a spark is provided on the northern border, then the “everything scenario” cannot be ruled out – even if it now seems a very distant prospect.