Real economies and financial markets: Outlook for 2019

The future of the world economy depends on three sets of variables: policymakers’ ability to adjust to the end of generous monetary policies, their willingness to recognize the need to engage in structural reforms, and the possibility that significant shocks occur.

In a nutshell

- Financial markets are hesitant as sources of concern pile up, including the possibility of a trade war or crash in China

- The future condition of the world economy also hinges on how governments will respond to the near end of cheap financing

- Yet, unless major shocks occur, a crash is not in sight

Fear and prudence prevail in most financial markets. Observers point to several sources of concern. The markets believe that two of the world’s largest economies – the United States and China – cannot expand any faster: in 2018, they are expected to grow at 2.9 percent and 6.7 percent, respectively, and to slow down in the future. The eurozone, meanwhile, has already reduced its gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate from 2.6 percent in 2017 to about 2.0 percent in 2018.

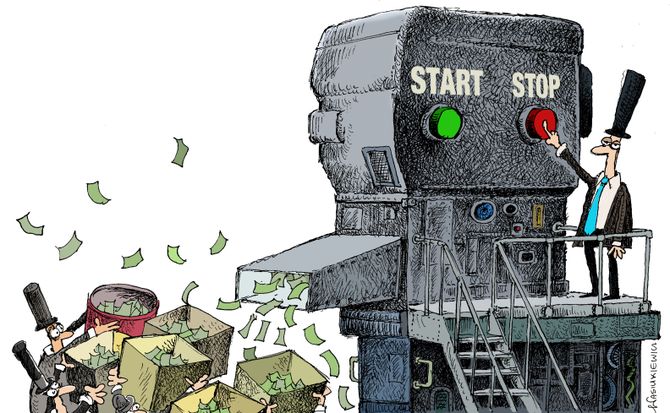

Monetary policy in the dollar and the euro areas may further rein in growth. U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell seems happy to let the monetary tightening continue. During the past year, the interest rate on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds has increased from about 2.37 percent to about 3.20 percent and might increase further.

To U.S. President Donald Trump’s dismay, this will have a negative impact on debt-financed consumption and investments, and will also lead to a rise in the dollar and a widening of the trade deficit.

Big uncertainty

Moreover, nobody knows to what extent the end of quantitative easing (QE) will affect interest rates on euro-denominated securities, so business might cool off until the picture becomes clearer.

The overall climate between the U.S. and China has improved, but investors realize that this is not the saga’s end.

The third source of concern stems from the public-debt situation in a number of European Union economies, including Italy. Should the public-finance context in these countries deteriorate significantly, a domino effect might follow and sap confidence on a much broader scale. Finally, one should not forget about the future of the trade tug-of-war started by President Trump at the beginning of 2018. The overall climate between the U.S. and China has improved over the past few weeks and could brighten up in the coming weeks, but investors realize that an end to this saga is not yet in sight. Even if November brings good news, 2019 is still fraught with uncertainty.

Cautionary moves

Financial markets have moved accordingly. The U.S. stock exchange is more or less where it was at the beginning of 2018, but the Japanese and German indices are about 5 percent and 12 percent lower, respectively. The index for the Chinese market is also in the red territory (about minus 20 percent). This is both good and bad news.

The good news is that, by now, all potentially untoward events are already factored into the current prices. Unless the trade war breaks out or the euro area disintegrates, 2018 can turn out to be a year of transition, during which financial markets have experienced relatively high volatility. Furthermore, investors have observed that corporate profits have not risen as fast as in the past, as they reflect the new global growth and money market conditions. The bad news is that this correction could be just the beginning of the story and that more substantial shake-ups may lurk down the road.

Indeed, one could argue that much of the drop that has characterized 2018 took place in the eight weeks of September and October and that if interest rates keep rising, investors will likely adjust their portfolios by selling stocks and flocking back to bonds. “Sell before the crash” would replace “buy on the dip.”

Questions and answers

The upshot is that during the next several months we will be facing one of two scenarios, depending on the answer to one crucial question: Do we believe that financial markets follow the evolution of the real economy and that, as long as major shocks do not occur in global GDP, credit or inflation, the financial situation will also stabilize?

This would be the case, for example, if financial markets were currently discounting the probability that firms’ profits will grow at a relatively slow pace and that, therefore, shares are not as attractive as in the past.

We may also believe that financial markets are, in fact, anticipating what will happen over the next few months. In this case, and in contrast to what the official figures for 2019 predict, one should expect the present global slowdown to continue for some more time.

Let us follow up on the first answer, which posits that financial markets follow the real economy. As mentioned earlier, investors are edgy. They no longer trust forecasts, including those regarding the EU, where the deteriorating economic climate has been causing the leading institutions to revise their projections almost monthly. In this context, it is clear that alarming headlines have an impact and add to volatility. In turn, volatility and uncertainty scare investors away from stocks and push them into less-risky forms of investment – including liquidity and highly rated government bonds.

Of course, this trend, quite visible in the eurozone, is less pronounced in the U.S. and Asia. But things could worsen. For example, it is not clear how the Trump administration will react to the reportedly increasing U.S. budget deficit (in 2018 it rose 25 percent with respect to 2017 in nominal terms, from 3.4 percent (2017) to 4.0 percent of GDP), which is inflating public debt (105.2 percent of GDP) and pushing interest rates up into dangerous territory. Likewise, we lack clarity on whether or not Mr. Trump will accept the conciliatory trade proposals recently floated by the EU and China and choose other venues to accentuate his views on free trade.

The near future will probably be characterized by a stable real outlook and financial pessimism.

China also remains a source of uncertainty, both because observers doubt the quality of the growth figures the authorities release and because it is feared that the Chinese policymakers might engage in further expansionary policies – rather than structural reforms – to compensate for the declining trend in China’s GDP growth. If that were to happen, a soft landing could quickly turn into a crash and the reverberations on the global economy would be substantial.

Scenarios

To summarize: if one accepts the view that financial markets are going to be bullish or bearish depending on the level of uncertainty, the near future will probably be characterized by a stable real outlook and financial pessimism. We believe this is the most likely scenario.

Let us now turn to the second possible answer: Do markets anticipate the future rather than follow the real economy? If one thinks so, the logical conclusion would be that it will take some time before the world economy bottoms out. But enter the China variable: it is no mystery that problems keep piling up there. If they get out of control, a financial crisis would indeed turn into a strong blow to the entire economy, with consequences throughout the world.

As mentioned earlier, during the past months, prices of stocks and bonds have declined worldwide – more than data about the real economy would justify. Following this line of reasoning, one should expect some further deterioration of the economic climate. In our opinion, this view has merit, but only in a long-term perspective.

The Western world suffers from insufficient productivity growth, a problem that can be addressed only with significant reforms in the regulatory frameworks of many countries, as well as in their educational systems. It will take time before policymakers acknowledge the need for such changes, and before they act accordingly. In the meantime, the decline will be smooth. Deviations from the soft landing path could certainly occur, but only if the real economy finds it difficult to adjust to the end of the easy monetary policy or if a significant shock materializes (e.g., the Chinese collapse, the Italian crisis, or an all-out trade war). Since these are distant possibilities, financial markets have not accounted for them.

We are likely heading toward a period in which financial markets and the real economy will follow partially different paths. Financial markets will be driven by uncertainty. Yet, it will not be a question of uncertainty about the real economy, but rather about what policymakers will do. Since the financial community expects erratic responses, volatility and mild pessimism will follow.

By contrast, we believe that during the next quarter, the real economy will shed the monetary hangover, while policymakers will try to redress the damages caused by fiscal profligacy. In the long-term, however, reverting to healthy, productivity-friendly policies will be neither easy nor painless. It is tempting to read the structural problems of the Western world as if they were a cyclical issue. If policymakers adopted this perspective, radically different and very dark scenarios would unfold.