Zimbabwe: Dashed hopes for meaningful change

After the 2017 coup d’etat ended the rule of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, his successor Emmerson Mnangagwa promised to conduct reforms in the bankrupt country. But the new president has ties to the old regime and maintains some of its worst practices.

In a nutshell

- Zimbabwe is again on the brink of economic collapse

- Corruption and instability have driven investors away

- The new leader has not altered the way the country is governed

The policies of the late Zimbabwe ruler Robert Mugabe (1980-2017) – which included the Fast Track Land Reform (FTLR), compensation for war veterans, “indigenization” practices and systematic violence during electoral periods – were guided by his urge to secure power at any cost. Not surprisingly, when a 2017 palace coup ended his rule, Zimbabweans felt they were finally entering a new era. And while his successor President Emmerson Mnangagwa was part of the ancient regime, he appeared committed to economic transformation, reengagement with the West and political reform. Two years later, Zimbabwe is again on the brink of collapse.

Signs of change

The year that followed Mr. Mnangagwa’s November 24 inauguration, 2018, proved promising. A high growth rate of 6.15 percent – driven by overall stabilization, higher agricultural production and increasing consumer and investor confidence – was accompanied by improvements in the country’s fiscal and external debt position. Also, the interim government adopted measures signaling a break with the past.

Restrictions imposed by the 2008 Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Act – namely, the 51 percent local shareholding requirement – were reverted, with exceptions for the mining sector and 12 additional “reserved” sectors. The latter are now reserved not for “indigenous Zimbabweans” but for “citizens of Zimbabwe.”

Citizens also suffer from fuel shortages, frequent power cuts, empty shelves in the supermarkets, rising food insecurity.

Furthermore, a more conciliatory approach was adopted toward the white farmers whose lands had been expropriated during the FTLR. As part of this reform drive, Mr. Mnangagwa also signed into law the Corporate Governance Act, which aims to improve the management of Zimbabwe’s 107 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and parastatals, and announced a series of privatization deals.

Back to 2008

Today, however, Zimbabwe’s situation is disturbingly similar to 2008. It features a valueless currency (following the end of a multicurrency regime) and an inflation rate that hit 300 percent in October 2018, the highest in the world after Venezuela. Citizens also suffer from fuel shortages, frequent power cuts (lasting up to 18 hours a day), empty shelves in the supermarkets, rising food insecurity (7.7 million people are now food insecure, according to the World Food Program). The number of Zimbabweans living in extreme poverty surged by 5.7 million between 2018 and 2019, an increase of one million.

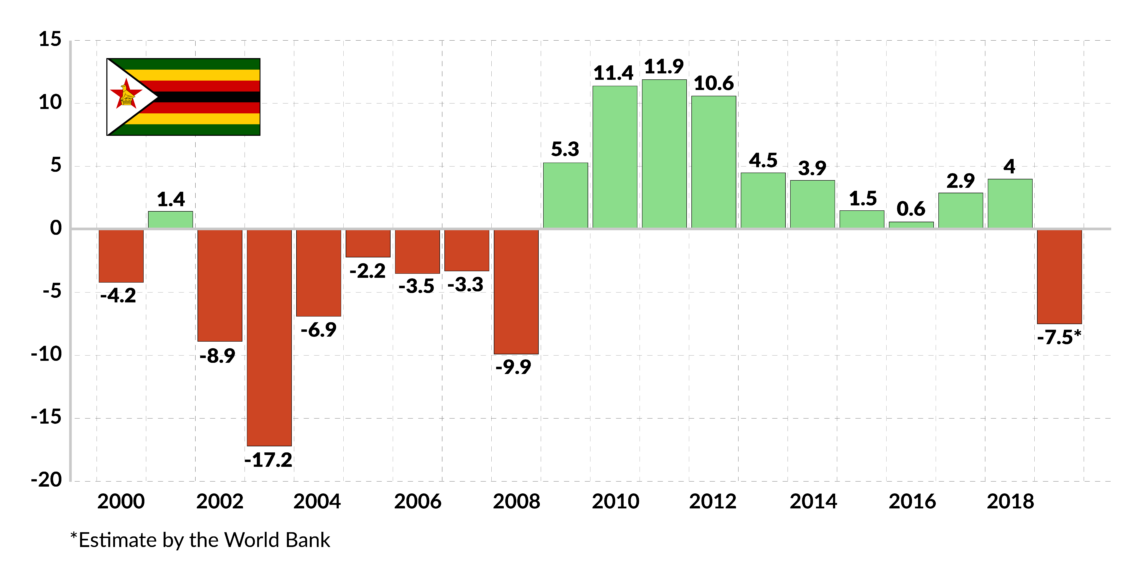

Severe drought and the Idai, one of the worst tropical cyclones on record (which made landfall on March 14, 2019), harmed food production and mining activity. However, Zimbabwe’s near economic collapse is due primarily to years of inadequate planning and erratic policy implementation. In addition, rampant corruption triggered chronic macroeconomic instability and drove away investors in droves. The country’s lack of economic resilience became obvious in 2019, when the gross domestic product contracted by 7.5 percent following a brief spurt of growth in 2018.

Facts & figures

Old habits die hard

Even with adequate policies, the road to recovery would be long and tortuous. A closer look at the country’s political dynamics reveals that the end of Mr. Mugabe’s rule has not altered the strong-arm style of Zimbabwean politics.

The first sign of trouble surfaced during the 2018 general elections, when security forces resorted to violence to contain the supporters of opposition parties agitated by accusations of electoral fraud. The two pillars that sustained Mr. Mugabe’s power for decades – the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party and the military – are still neutralizing the political and civil opposition through repression and co-optation. Restrictive regulations remain in place and so does the habit of resorting to violent measures and unconventional mechanisms such as arbitrary arrests and abductions, and internet and social media shutdowns. In January 2019, more than 17 people were killed by security forces while protesting against higher fuel prices.

Conscious of the consequences of repression at a time when Zimbabwe desperately needs to engage with international donors and investors, President Mnangagwa is trying to co-opt the opposition, as reflected by the creation of the Political Actors Dialogue (POLAD) – a platform joining opposition parties and the ZANU-PF. This platform has no significant power and does not include the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), the main opposition party (in 2005 split into two) and sole political force that can effectively challenge the ruling coalition.

There have been other episodes further eroding hope for change. In a display of continuity with the old order, the government recently announced that major roads and buildings would be renamed after national heroes, including 10 streets named after Mr. Mnangagwa himself. The president also adopted his predecessor’s blame-shifting narrative, claiming that the economic collapse of Zimbabwe is the direct result of sanctions imposed by the United States. Also, he continues to tighten his grip on power through legal engineering, such as a recent constitutional amendment that allows the president to appoint and promote judges.

Possible game changers

In 2017, mounting social unrest, Mr. Mugabe’s frailty and division among the ZANU-PF created the perfect conditions for a political shift. However, because of the undemocratic and militarized nature of power in Zimbabwe, change was designed and controlled by an alliance between two old political actors: a faction of ZANU-PF led by Mr. Mnangagwa (opposed to then-President Mugabe), and the Zimbabwe Defense Forces under the command of General Constantino Chiwenga.

President Mnangagwa’s power may be under threat from South Africa.

The changes that followed the coup have been perfunctory. However, as in 2017, the power balance within the ZANU-PF and between the president and the military remains fragile. While the opposition’s room for maneuver is extremely reduced now that its 2017 momentum has vanished, President Mnangagwa’s grip on power may be less solid than it appears on the surface.

Events following the 2018 elections suggested tensions between the president and Vice President Chiwenga, who is said to have presidential ambitions. The fact that Mr. Mnangagwa managed to secure the ZANU-PF endorsement as the presidential candidate in the 2023 elections was an important sign of force vis-a-vis the general. The sitting president is also consolidating his position in institutional terms. The recent Constitutional Amendment Bill repeals the joint election of the president and two running mates. Instead, vice presidents will be directly appointed by the president, who has the power to dismiss them. It is important to note, however, that Mr. Mnangagwa has benefited from Mr. Chiwenga’s prolonged absence. The general spent several months in China to receive medical treatment (high-level defense ministry sources alleged polonium-210 poisoning, but this should be taken with a grain of salt, as physical sickness is perceived as weakness in Zimbabwe).

The inevitable repressions may lead to further isolation of the regime and new international sanctions.

An important sign that President Mnangagwa’s power may be under threat comes from South Africa. Pretoria’s “quiet diplomacy” in Zimbabwe was helpful to the ZANU-PF and Robert Mugabe, especially during the negotiations of the Global Political Agreement, which followed the controversial 2008 elections. However, as evidenced by recent xenophobic attacks against immigrants, many from Zimbabwe, in South Africa, the Zimbabwean economic crisis has a destabilizing effect on its neighbor.

Former South African president Thabo Mbeki (1999-2008) has acknowledged Zimbabwe’s crisis, a fact that has regional ramifications, both economic and political. Mr. Mbeki, whose “quiet diplomacy” in Zimbabwe has been blamed for extending the survival of Robert Mugabe’s regime, recently went to Harare to hold a private meeting with MDC leader Nelson Chamisa. This move by Pretoria suggests that President Mnangagwa may be pressured to enter into an agreement with the real opposition to his regime.

Scenarios

Considering Zimbabwe’s current economic and political situation, three scenarios should be considered.

Most likely: power consolidation

The first and most likely one posits further power consolidation combined with deepening economic deterioration in the short term. President Mnangagwa will maintain the support of the ZANU-PF and part of the opposition owing to patronage and co-optation. With an increasingly alienated Gen. Chiwenga, he may also benefit from the support of the security forces, which would deter Pretoria from taking active measures against Mr. Mnangagwa. However, under this scenario, his power remains likely to be challenged in the medium term. As the economic situation is expected to further deteriorate in 2020 – amid higher unemployment, salary cuts and a possible decrease in remittances from the diaspora – Zimbabweans may take to the streets in protest, feeling they have little left to lose. As a result, the inevitable repressions may lead to further isolation of the regime and new international sanctions.

Less likely: economic collapse

The second, less likely, script is one of economic collapse combined with political destabilization and subsequent militarization in 2020. This scenario could occur if the government loses its capacity to pay the salaries of the security forces. Unable to fall back the military in the face of violent protests triggered by rising poverty, famine and the collapse of the health and education sectors, Mr. Mnangagwa would find himself cornered. In such a case, the Zimbabwean armed forces could remain loyal to Vice President Chiwenga and senior officers could engineer a process of leadership change.

Least likely: mediated solution

The third and least likely scenario is that of a mediated solution driven by international pressure and intervention from Pretoria. In theory, such outside actors could pave the way for another government of national unity. (The precedent was set in February 2009, when a coalition consisting of President Mugabe’s ZANU-PF, Morgan Tsvangirai’s MDC-T and Mutambara’s MDC formed a government that lasted until 2013.) Like a decade ago, such a coalition could help improve the country’s economic condition. However, MDC leader Nelson Chamisa is not expected to accept a similar deal: the previous unity government gave more power to Mr. Mugabe and the ZANU-PF and weakened the MDC.