Scenarios for the airline industry after Covid-19

While the airline industry was booming throughout the 2010s, the Covid-19 outbreak left it reeling. Governments around the world are bailing out flag carriers, leading to potential market distortions.

In a nutshell

- Airlines will recover more slowly than expected

- Government aid could create market distortion

- Aviation companies will look for new business models

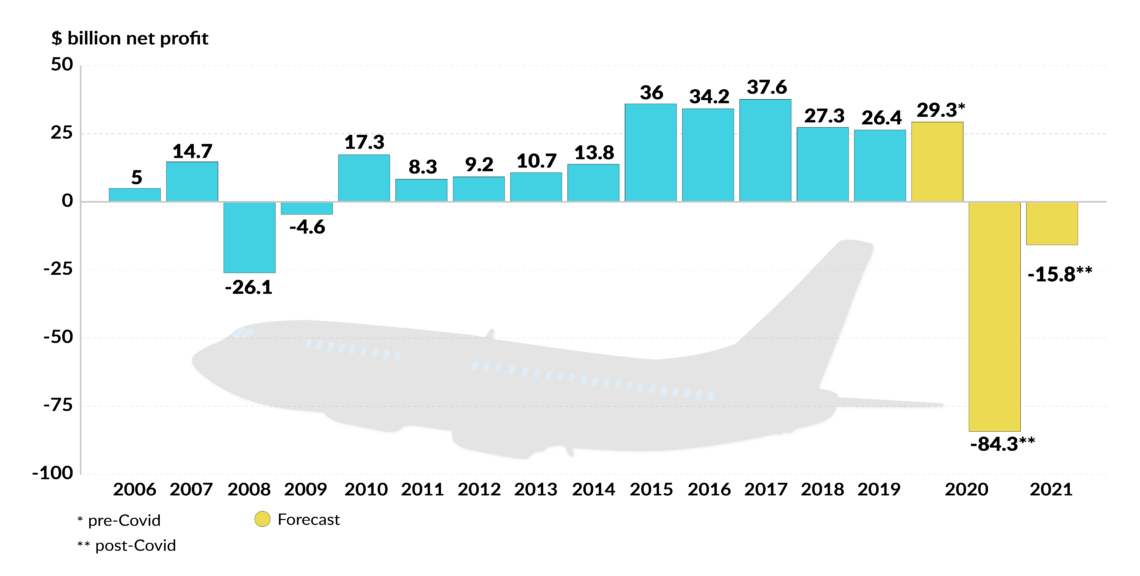

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, the number of flights was steadily increasing. In 2019, numerous airports hit new traffic records. Now, the aviation industry is considered one of the main economic casualties of the coronavirus crisis.

Global air traffic has come to a near-complete standstill in recent months. The little activity that remained consisted mostly of passenger planes transporting cargo. While flights across Europe saw a modest increase in May 2020 compared to April 2020, the number of flights operating daily in European airspace declined by up to 90 percent compared to May 2019.

European aircraft manufacturer Airbus said it is cutting production of some of its best-selling aircraft by a third, while others have suspended production entirely. There is consensus in the industry that aviation will not return to pre-pandemic numbers before 2022.

To avoid bankruptcy, airline operators are seeking ways to reset the supply chain and create sustainable business models.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Changes aboard the aircraft. Airlines will need to adjust to new health and safety guidelines. Middle seats may have to be left empty to reduce transmission risks.

The European Commission left the drafting of new requirements to the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). On May 21, 2020, EASA put forward its initial guidelines, which stipulate that physical distancing rules should be observed to the extent allowed by the passenger load and cabin configuration.

Quick recovery unlikely. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) recently estimated that commercial airlines worldwide would lose approximately $314 billion in revenues in 2020. Their initial scenario, based on severe and lengthy travel restrictions, predicted losses of $252 billion. The new figures reflect a crisis that runs deeper than originally expected. A V-shaped recovery is improbable; realistically, uptake will be U-shaped.

Competition issues. The pandemic has pushed many airlines to the brink of bankruptcy. According to CAPA (Centre for Aviation), by the end of May 2020, most airlines in the world would have been bankrupt without government intervention. While such handouts have been welcomed by the aviation industry, they pose challenges too.

Airline operators are seeking ways to create sustainable business models.

On March 19, 2020, The European Commission adopted a temporary framework for state aid to give its member states more flexibility in supporting their economies during the Covid-19 outbreak. Recognizing the gravity of the threat, the EU allowed national grants, selective tax advantages, advance payments, loans and other similar measures. The commission has declared that bailouts would be subject to controls to limit possible distortions to competition. However, so far a patchwork of bailouts has been carried out without foresight or strategy.

The commission has already approved state aid for numerous European airlines, including Paris’s 7 billion euros in urgent liquidity to support Air France, Denmark’s public guarantee of up to 137 million euros to compensate SAS, and Sweden’s half-billion-euro support package for SAS and other Swedish airlines. Furthermore, on May 29, 2020, European Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager announced the EU would not oppose Germany’s 9 billion-euro bailout of Lufthansa, the biggest airline bailout resulting from the pandemic so far.

Meanwhile, Dublin-based Ryanair found itself excluded from national state aid schemes. The company stated that the bailouts approved by the EU are distorting the market, and has already filed several complaints with the European Commission. According to Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary, the airline is working on taking the bailout approvals to court. The company hopes to have filed between 10 and 15 cases with the European Court of Justice by the end of the summer.

For example, Ryanair – the largest airline in Italy by passenger volume – could soon face disruptive competition from Alitalia, which stands to receive $3.3 billion from the Italian government. Subsidies that favor flag carriers to the exclusion of rival airlines will create an inherently uneven playing field if grants are approved with no preconditions or considerations, which seems to be the case of late.

The main concern is that government aid is not being given to maintain essential operations, but rather for geo-economic reasons. With this approach, states will be funding cheap tickets to compete with low-cost companies like Ryanair once air traffic resumes. Commissioner Vestager herself expressed concern about the significant discrepancies in coronavirus state aid among member states, saying there was a risk of distorting the EU single market.

If the EU Commission does not halt its recent practice of unconditional approvals, bailout disparities will pose a considerable threat to the market in the long run. A failure to coordinate measures will likely lead to less competition, creating dominant market players backed by governmental support. Moreover, state aid legal proceedings may not only become a costly affair, they also risk creating financial uncertainty for shareholders, substantially slowing economic recovery.

New business models

Nationalizations. Due to the economic impact of the pandemic and governments’ swift reactions, a renationalization is on the cards for many airlines. Several states have provided aid in exchange for ownership.

However, renationalizations would also considerably prolong the crisis due to the spike in debt that would be owed to governments. Moreover, from a corporate perspective, even with state aid, the shift in ownership could cause a dip in customer satisfaction levels and potentially create a ripple effect that would harm airlines long term.

Foreign stakeholders. Some troubled carriers are likely to continue struggling despite handouts. Their strategy to rectify the financial deficits, and governments’ response to market developments, will be paramount to the geopolitical state of play in aviation stocks.

Ryanair is working on taking EU bailout approvals to court.

While foreign investments are likely to be warmly welcomed by the EU, certain non-EU investments in European airlines could also pose a competitive risk. Even minority stakes could prove concerning for the European Commission if they allow non-EU countries to EU carriers and distort competition. If foreign stakes in European airlines spike, the commission will likely take a clear political stance against such practices and intervene.

Mergers. While airlines with substantial debt are searching for ways out of the crisis, consolidation could become a go-to choice for several companies – provided it does not distort competition.

Where struggling airlines have a strategically important market position, they could become absorbed by airlines that are quicker to recover from the financial downturn following regional air traffic uptake and better customer flow or viable state aid injections.

However, airlines that are interested in acquiring competitors should expect to face heavy political and regulatory scrutiny, as authorities are not likely to ease merger and antitrust procedures in light of the current crisis.

Aircraft lease. Airlines do not always own their planes. Leasing, where aircraft are bought by lessors and rented to airlines, is common. Now that the travel restrictions caused a surplus of aircraft, a growing number of airlines are searching for ways to terminate their lease contracts, leaving lessors exposed to economic hardship.

In April, Brussels Airlines scrapped its lease contract for numerous aircraft with CityJet, while budget carrier SpiceJet returned a number of leased aircraft to Turkey’s Corendon Airlines. However, aircraft leasing could become a viable option for many airlines in the longer term.

Inconsistencies with EU Green Deal. While the aviation industry adjusts to government bailouts and changes to its business models, the need for the industry to meet its environmental targets has not disappeared. Governments around the world are considering several exemption mechanisms, including the postponement of taxation measures to the aviation sector to relieve airlines, in response to the industry’s request that legislators halt green changes until the industry is back on its feet.

However, the EU seems headed in the opposite direction. Certain EU countries want to fast-track green initiatives, including a tax on jet fuel. While companies like Air France-KLM requested that plans to impose green taxes be postponed, France nonetheless introduced a tax on flights earlier this year, while the Dutch government voted to move ahead with a green tax on flights at the end of March.

Certain EU countries want to fast-track green initiatives, including a tax on jet fuel.

The two countries insist on an EU-wide approach, advocating an exceptional derogation to the EU bloc’s requirement of unanimity on taxation matters, on the grounds that the issue is an environmental concern. This has recently led to an EU evaluation on energy taxation, paving the way for the French-Dutch ambitions.

In parallel, the European Commission plans to reboot the economy with a 750 billion-euro rescue package. The EU plans to finance this massive recovery fund by extending its emissions trading system to the aviation industry. Some parties within the bloc would also like to see any future bailout for European airlines to come with green requirements – among others the Austrian government, which has recently approved a 600 million-euro aid package for Austrian Airlines on the condition that several environmental changes be carried out.

This string of mixed signals is creating uncertainty in the sector, hindering recovery. Should the EU move forward with these measures while the rest of the world gives aviation companies a much-needed break, European carriers would be at serious risk of a competitive disadvantage.