Angola’s oil comeback: Cautious optimism

After experiencing a meteoric rise following the end of the civil war in 2002, the oil industry in Angola came tumbling down with the 2008 oil price crash and never recovered. Several recent developments indicate that a partial return to health could be on the horizon.

In a nutshell

- In 2008, Angola appeared set to overtake Nigeria as Africa’s largest oil producer

- The oil price crash drastically reduced production, and the Angolan government failed to revive investment when prices rose again

- Reforms enacted under President Joao Lourenco could reverse this trend

A few years after the end of the civil war that ravaged the country for 27 years, Angola made world headlines. In the first postwar oil licensing round held in 2005-2006, the country, which is the second-largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, received a then record-breaking signature. Such an outcome would be inconceivable today. Both the Angolan oil sector and the economy have suffered since, even when oil prices were high. A combination of above-ground factors has diminished interest in Angola’s oil, with government policies and poor sector governance sharing the blame with fundamental changes in global oil markets.

Angolan President Joao Lourenco, elected in 2017, has vowed to reverse this situation and has announced sweeping reforms in the oil sector and the economy at large. There should be no doubt that much-needed reforms, if properly implemented, are good for the Angolan economy, which is one of the most oil-dependent in the world. However, they are unlikely to elevate Angola back to the prominent position it held a decade ago. The president’s commitment to the reforms will be tested.

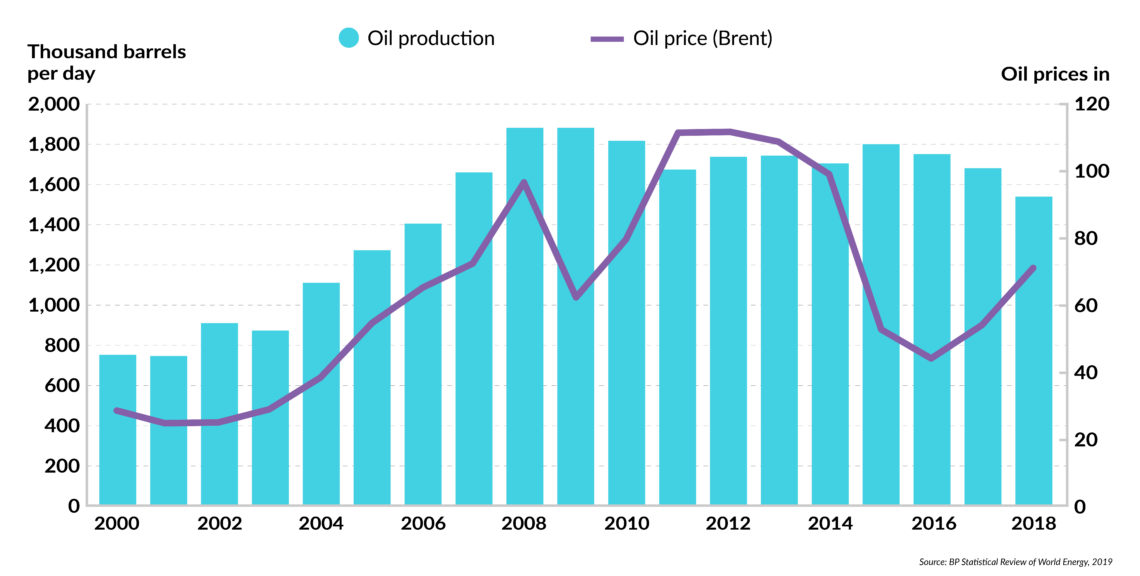

Heyday

Angola’s oil industry experienced a golden age as soon as the civil war ended in 2002. Oil production increased rapidly in the following six years and reached a peak of nearly 1.9 million barrels a day (mb/d) in 2008 – more than twice the production of 2002. Angola was billed as well on its way to becoming Africa’s biggest oil producer in the following decade, overtaking Nigeria. Confident about its future, Angola joined OPEC in 2007.

President Joao Lourenco has announced sweeping reforms in the oil sector.

International interest in this new African hot spot was equally impressive as international companies rushed to gain a foothold in the relatively unexplored country. In the licensing round of 2005-2006, the national oil company, Sonangol, invited companies to bid for seven offshore blocks. Competition was intense with over 50 companies qualifying; and the result of an aggressive bid-round was impressive. Italian Eni offered $902 million for a 35-40 percent-operating interest in one of the blocks. Two other blocks received what was then the highest signature bonus for a block in the history of the oil industry, with Sonangol and China’s Sinopec offering $1.1 billion for each block.

Then came the oil price crash of 2008. Although oil-producing nations the world over suffered, several managed to resuscitate their industry as oil prices recovered. Angola, however, lagged behind its peers. In 2018, oil production reached its lowest level since 2007.

Facts & figures

Oil in Angola

- Oil production in Angola started in 1955

- Angola’s civil war erupted after the country gained independence from Portugal in 1975

- Angola is Africa’s second-largest oil producer after Nigeria and third-largest economy after Nigeria and South Africa

- Angola is the third-largest economy and second-largest oil exporter in sub-Saharan Africa

- Angola is the 10th biggest gas-flaring nation in the world after Russia, Iraq, Iran, U.S., Algeria, Venezuela, Nigeria, Libya and Mexico (World Bank, 2019)

- Sonangol typically holds a 20% stake in Angolan oil blocks through its subsidiary Sonangol P&P

- In December 2018, Angola received a $ 3.7 billion financing program from the IMF

- Angola’s proven crude oil and natural gas reserves stood at 8.16 billion barrels and 383 billion cubic meters respectively in 2018 (BP, 2019)

- Angola’s proven crude oil reserves rank 16th in the world and third in Africa after Libya and Nigeria

- Sonangol ranks 29th out of 74 on the Natural Resource Governance Institutes’ Resource Governance Index, performing worse than the Ivory Coast’s Societe Nationale d’Operations Petrolieres de la Cote d’Ivoire and Venezuela’s Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. (NRGI, 2017).

Drastic turn

Angola struggled to sustain production growth because investment could not be maintained. As a result, not enough discoveries were made to offset the decline in maturing fields. After reaching 9.5 billion barrels in 2008 compared to 4 billion barrels in 1998 (a nearly 140 percent increase), Angola’s proven oil reserves shrank to 8.4 billion barrels. Under existing conditions, the country’s reserves to production ratio is only 15 years.

The oil price collapse in 2008 provides some explanation for Angola’s weak production performance. The country, however, failed to revive interest even when prices recovered between 2010 and 2014, when they hovered around $ 110 per barrel. Other factors are to blame.

Oil production in Angola is largely concentrated in deep waters, where investment and operating costs are significant. In addition, contractual terms are relatively tough, meaning the total government share out of an oil project can exceed 90 percent – a share that is typically found in countries that sit on much bigger and lower-cost reserves like Iraq. As a result, several discoveries have remained undeveloped in Angolan waters because of poor economics – the so-called marginal fields.

Oil production is largely concentrated in deep waters, where investment and operating costs are significant.

More broadly, Angola suffers from endemic corruption. Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (2018) ranks Angola 165th out of 180 countries, with the remaining 15 countries largely considered failed states. It also performs poorly in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ranking, placing 173rd out of 190 countries in 2019.

In addition to Angola’s challenging domestic business environment, changing external conditions exacerbated the situation. The shale revolution in North America, which commenced in earnest around 2010, fundamentally changed oil markets, putting downward pressure on prices. It also significantly boosted the status of the U.S. as a major oil supplier. Most relevantly, tight oil is of the “light” variety, thereby directly competing with West African oil in its key export markets. In fact, the first barrels replaced by the shale revolution were exports from West Africa to the U.S.

Furthermore, the peak oil supply fears that dominated most of the last decade and largely supported the perception of dwindling opportunities for investment around the world have simply vanished post-shale. Today, the overriding perception is that supplies are plentiful, demand is weak and attitudes toward international capital are more welcoming around the world.

Facts & figures

Angola oil production and oil price, 2000-2018

Economic stress

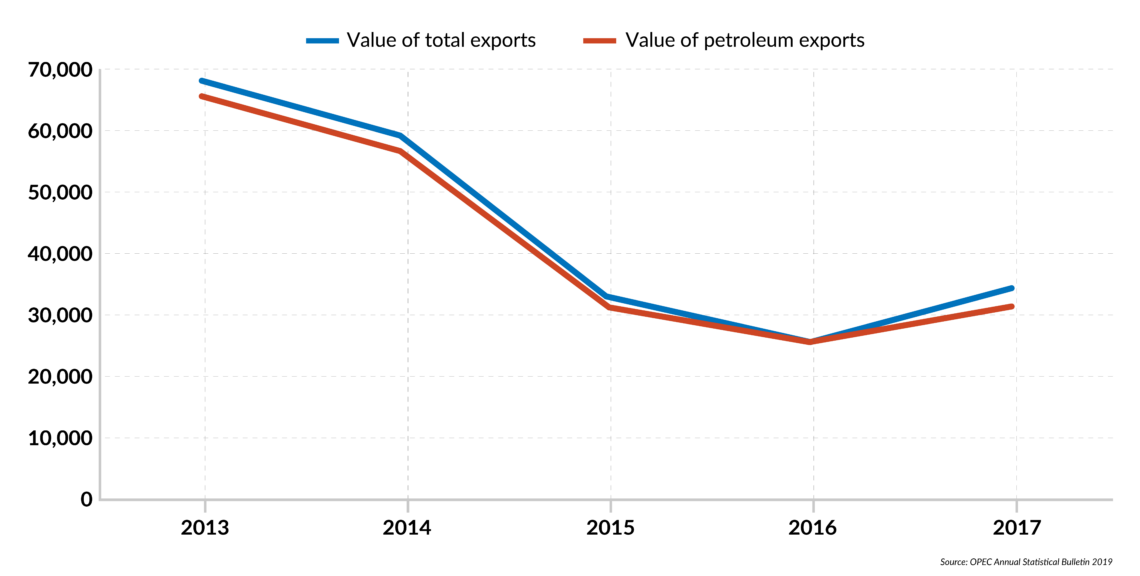

The combination of lower oil prices, declining production and unsustainable policies has put the Angolan economy under stress, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Angola is one of the world’s least diversified economies. Oil provides 50 percent of GDP, over 70 percent of government revenue and more than 95 percent of exports. The economy is therefore fully exposed to developments in the oil sector, both domestically and globally.

World Bank data shows that Angola’s economy remained in recession in 2018, with growth falling sharply as oil production stayed weak due to maturing oil fields. Following the oil price collapse in the summer of 2014, Angola’s fiscal revenues declined by 51 percent between 2014 and 2017, while public infrastructure spending was down 55 percent, according to the United Nations.

The sovereign wealth fund, Fundo Soberano de Angola (FSDEA), established in 2012, was supposed to support “Angola’s socioeconomic development by creating wealth for the Angolan people,” using oil revenues. The fund’s poor management, however, clearly counterbalanced its purpose.

Facts & figures

Angola total exports and petroleum exports 2013-2017

New chapter

Recognizing the challenges facing his country, President Joao Lourenco has enacted several reforms, including some targeting the oil sector, as soon as he assumed office in 2017. His election marked the start of a new chapter in the history of Angola after the 38-year reign of former president Jose Eduardo dos Santos (from 1979 to 2017).

The new president has clearly set out his priorities: diversify the economy, improve the business climate, fight corruption and boost investment in oil and gas. Speaking at the 74th session of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2019, he declared that Angola was now open to the world and to foreign investment in all areas of its economy. An anti-corruption unit was created in March 2018 and high-profile officials believed to be involved in wrongdoing were dismissed and/or prosecuted, including Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of the last president and former Sonangol head, as well as his son, Jose Filomeno de Sousa dos Santos, who chaired the country’s sovereign wealth fund.

Sonangol will be required to sell its stakes in several non-core ventures. Its role will also be confined to an exploration and production company after wearing the double and conflicting hats of being the government commercial entity and the sector’s regulator for years. Under the latest reforms, a new agency – the Angolan Petroleum, Gas and Biofuels Agency (ANPG) – was set up to regulate, supervise and promote the execution of oil activities, a mandate which was formerly held by Sonangol. The ANPG will manage oil and gas contracts, execute government policies and promote investments in the sector. It is also responsible for the licensing rounds and allocation of blocks. The separation of the operator and regulator roles is an important step in establishing better governance of the oil sector.

The government announced a plan to auction off more than 50 oil and gas blocks between 2019 and 2025.

After more than eight years of licensing round suspension, the government announced a plan to auction off more than 50 oil and gas blocks between 2019 and 2025, hoping that this will lead to new discoveries, thereby halting the production decline. In order to whet investors’ appetites, the government introduced several regulatory and fiscal changes, including halving tax rates on small and marginal fields. Similar changes were also applied to encourage investment in natural gas, which was mostly flared for years because of a lack of infrastructure for the exploitation of associated gas (a by-product of oil production).

Scenarios

Recent developments in Angola’s oil industry indicate that the sector’s reforms are already having some positive impact, though expectations should remain sensible.

Eni attributed the five discoveries it made in 2018/19 to the new regime, stating it certifies “the concrete validity of the recent legislation.” Eni’s discoveries will boost potential investors’ appetites at forthcoming licensing rounds.

Other factors, however, will be factored in when assessing the attractiveness of the investment proposition in Angola, including the effective implementation of the announced reforms and the continuous dedication of the current administration to such reforms. Equally important is the sentiment in global oil markets, particularly price expectations. Under existing market conditions, Angola will have to acknowledge that the last decade’s fat signature bonuses are a thing of the past.

All in all, it seems that Angola is on the right path to improve the status of its oil and gas industry and subsequently its economy. However, unless large discoveries are made, Angola is unlikely to see its recent production trends reversed. Even if such finds materialize, it will be several years before reserves turn into production.

Furthermore, it will be interesting to see the extent to which Angola will tolerate the loss in revenues as a result of the latest fiscal changes, especially if they don’t result in discoveries and increase in production. Recent experience in countries like Mexico indicates how governments’ expectations, which are generally short term, often fail to match the industry’s realities: oil and gas projects are by nature long-term with extensive lead times between investment and production, which is even truer for deepwater projects. When the industry fails to deliver in the short time span that fits a government’s schedule, the outcome can be a more aggressive attitude toward investors and even an unraveling of the reforms under shortsighted administrations. Perhaps Angola’s new president will prove more pragmatic.