Why Angola left OPEC

As OPEC strived to prop up oil prices with production limits for its members, Angola was caught between the organization’s policies and its own interests.

In a nutshell

- Angola joined OPEC mostly for prestige

- Soon after, the oil industry’s golden years ended

- Faced with OPEC’s persisting production limits, Luanda bailed out

In December 2023, Angola made the surprise announcement that it was leaving the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) effective January 1, 2024, severing a 16-year-long relationship. When the African oil exporter joined the producers’ group in 2007, it was the first country to do so since 1975. The relationship between Angola and OPEC changed drastically over that period.

The oil marriage deteriorates

Ahead of assuming OPEC membership, Angola’s then oil minister, Desiderio Costa, exclaimed, “We’ve been wanting this for a long time.” In sharp contrast, when announcing the country’s departure from the group, Mineral Resources and Petroleum Minister Diamantino Azevedo stated, “We feel that at this moment Angola gains nothing by remaining in the organization and, in defense of its interests, it decided to leave.”

This is the same minister who, in 2021, praised the producers’ group for its “astonishing success” in stabilizing oil markets following the collapse in oil demand and prices at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, and who described the cooperation between OPEC members and their allies, including Russia, in what is known as OPEC+, as a “trusted and proven relationship.”

The cracks had already started to appear in 2020 when OPEC+ announced historic production cuts of nearly 10 percent of global supplies to salvage oil prices. Not all members delivered on their promises, with Angola being one of the laggards, along with important players like Nigeria, Iraq and Kazakhstan.

By the summer of that year, faced with mounting pressure from Saudi Arabia and Russia in particular, Angola relented: it implemented the cuts and agreed to compensate for the delay. In the subsequent years, oil production from Angola struggled to regain pace. In June 2023, along with Nigeria and Congo, the African nation was given a lower production baseline – the level from which each member’s output quota is calculated. That riled Angola’s envoy: other members like the United Arab Emirates had their baselines increased. He walked out of the meeting. However, peace was quickly restored – the parties agreed to revisit the baselines three months later.

Yet, at the November 2023 meeting, Angola was still given a lower production quota for the coming year, reflecting its diminished production capabilities. Once again, the African producer rejected the ruling. “We will produce above the quota determined by OPEC,” Angola’s OPEC Governor Estevao Pedro declared. Angola said it would produce 1.18 million barrels per day from January 2024, around 70,000 above the 1.11 million barrels per day quota set out in the OPEC agreement. Shortly after, Angola announced it was leaving the group.

Many believed that the sharp increase in oil prices early in the 21st century was driven not only by demand but also because the world was running out of hydrocarbons.

Such a major strategic decision is unlikely to be solely driven by that squabble, considering Angola’s history of non-compliance. However, it seemed to be the straw that broke the camel’s back, leaving many questioning what the real drivers of the exit were and what it means both for the future of Angola’s oil industry and for OPEC.

Angola oil’s bygone golden years

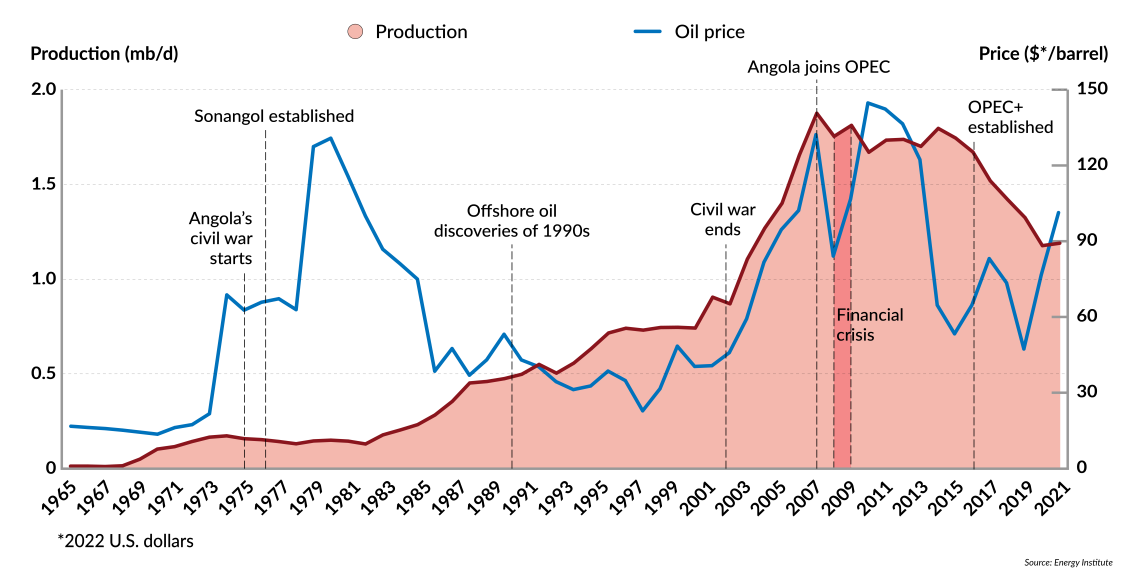

When Angola decided to join OPEC, its oil industry was experiencing a golden post-war era of rapid expansion that coincided with fast-rising oil prices in the first decade of this century.

After gaining independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola plunged into a devastating civil war that continued until 2002. Oil discoveries in the country had already been made in the 1990s, but the war constrained their exploitation and further exploration.

When the war ended, international oil companies were scrambling to find promising investment opportunities. Many believed that the sharp increase in oil prices early in the 21st century was driven not only by rapidly growing demand but also because the world was running out of hydrocarbons. Supply was struggling to keep up. Chinese national oil companies, in particular, were pursuing an aggressive strategy to secure oil and gas acreage, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Facts & figures

Angola’s crude oil production and oil prices

In 2005, Angola announced its first postwar licensing round to award oil blocks. Competition was fierce. The leading oil and gas companies battled to gain and expand their foothold in what was then Africa’s hottest investment destination. The fiscal terms imposed by the Angolan government were stiff: it would get more than 90 percent of all proceeds from oil projects. The consortium of Angola’s national oil company Sonangol and China’s Sinopec International offered the most generous signature bonus in the history of the oil industry: $2.2 billion for two oil prospecting rights in two of the blocks. That was an upfront payment made to the Angolan government before any activity started.

The financial crisis of 2008 forced OPEC to introduce several cuts, which were estimated to have limited Angola’s production by 10-15 percent in 2009 when Angola chaired the group.

Luanda wanted to capitalize on the energy sector’s popularity and expand its international standing by pursuing membership in OPEC, which controlled around 42 percent of world supplies. The Angolan oil ministry spokesman at the time, Bastos de Almeida, stated that joining OPEC would generate “deep advantages financially.”

In reality, the prestige of gaining a seat at the OPEC table and the desire to have a more notable influence on global oil markets lured Angola in, despite the dangers: its oil output would be constrained by production cuts and membership could disincentivize international investors. As one study put it, “OPEC’s perceived market power is a useful fiction that generates political benefits for its members with domestic and international audiences.”

Read more on Africa’s energy sector

- The curse of being stuck between oil and debt

- Africa’s energy hopes and fears

- Europe’s energy switch may boost African producers

For the Angolan government, however, that was a benefit well worth the small sacrifice of selling fewer barrels of oil should the need arise. Back then, production cuts were not seriously contemplated, as hardly anyone foresaw what was coming next.

Angola’s oil production slides

One year after Angola joined OPEC, oil markets changed, which had significant implications for both Angola and the organization. The financial crisis of 2008 triggered a crash in oil prices. It forced OPEC to introduce several cuts, which were estimated to have limited Angola’s production by 10-15 percent in 2009 when Angola chaired the group. Production has failed to recover since. In the subsequent years, the government consistently formulated overly optimistic production forecasts, according to the IMF, that were not aligned with the reality of an increasingly struggling sector.

Angola’s oil production hit a peak of 1.88 million barrels per day in 2008. Hopes for a licensing round in 2008 akin to the successful 2005-2006 round were dashed following dim interest from investors amid falling oil prices. When interest improved, it was a far cry from what Angola experienced pre-2008. Even though oil prices were above $100 per barrel, the 2010-2011 round saw limited bidding, with the highest signature bonus reaching $500 million. The reduction in investment exacerbated the decline in output, which translated into Angola’s shrinking exports and government revenues.

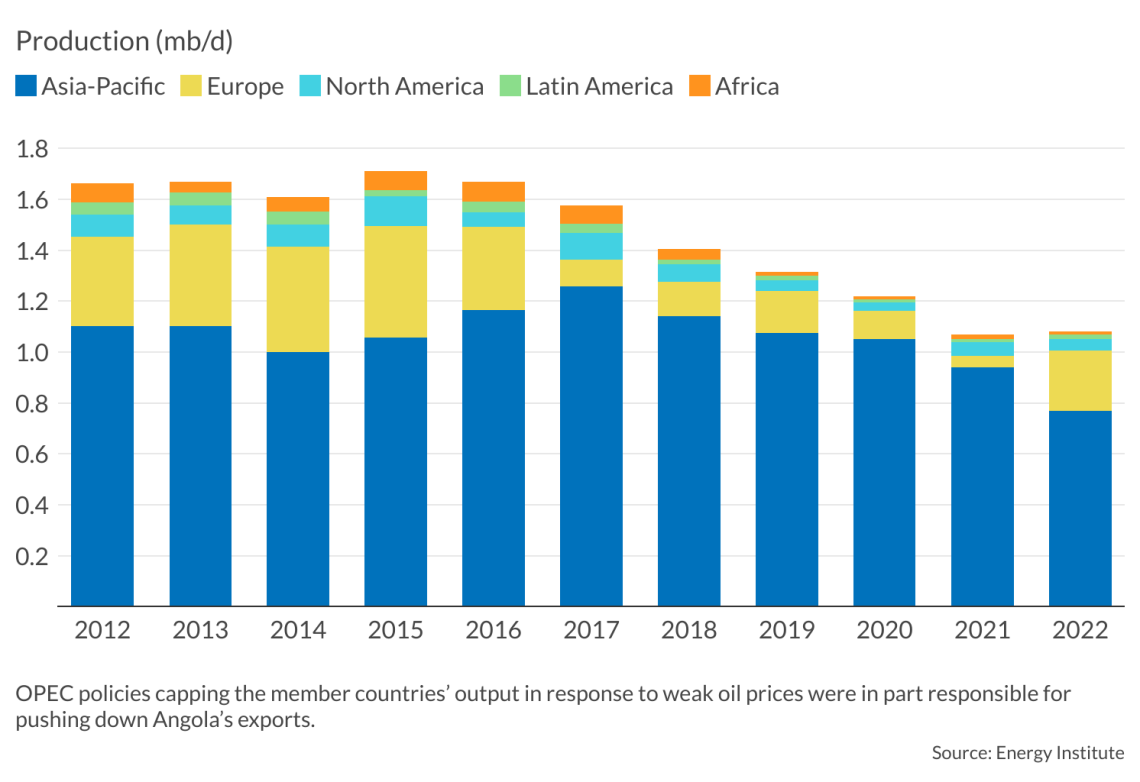

Meanwhile, the shale revolution in the United States, which started in 2008, created direct competition for West African producers, given the similarities in quality between shale oil and West Africa’s variety of oil. That caused Angola to lose market share in some of its key regions, especially in North America. The U.S., which was once its top buyer, turned into a strong competitor.

Facts & figures

Oil industry governance and policy changes

In 2017, Angola witnessed a leadership change. Joao Lourenco, former defense minister, succeeded Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who stepped down after ruling the country from 1979 to 2017. Mr. Dos Santos faced accusations of high-level corruption, especially in the oil sector, where he had appointed his daughter Isabel dos Santos as head of Sonangol. She was said to have become Africa’s richest woman.

The reforms appear to be paying off. The government hopes that the exploration opportunities it is promoting will represent half of the country’s future production.

Upon assuming office, the new leader ordered a 30-day review of the nation’s oil industry to address its challenges. He subsequently introduced several regulatory and fiscal changes, including the creation of the National Agency for Oil, Gas, and Biofuels, which would take over the responsibilities of overseeing, regulating and promoting activities within the oil and gas sector from Sonangol. It has been reported that President Lourenco wants to privatize the company by 2026. The president further announced lowering the fiscal charges, particularly on less productive fields, to appeal to investors, and launched the 2019-2025 hydrocarbon exploration strategy to boost discoveries. The government hopes that the exploration opportunities it is promoting will represent half of the country’s future production.

The reforms appear to be paying off. Italian firm Eni, a significant player in Angola, attributed a series of discoveries made between 2018 and 2019 to the government’s reforms. The licensing round launched in 2023 received considerable interest, with more than 50 bids offered.

Facts & figures

Angola oil facts

- Angola holds the 18th-largest proven oil reserves in the world (7.8 billion barrels or 0.4% of the global total) and the fourth-biggest in Africa, accounting for 6.2% of the continent’s proven reserves, after Libya (38.7%), Nigeria (29.5%) and Algeria (9.8%) – all of which are OPEC members

- Oil production in Angola started in 1955 from the Benfica onshore field

- Angola has a small domestic oil market, accounting for around 11% of the country’s oil production; the rest is exported primarily to the Asia-Pacific (71%) and Europe (22%) as of 2022

- Crude oil and oil products have accounted for approximately 96% of Angola’s total exports, 56% of fiscal revenues and 34% of Angola’s total real gross domestic product (IMF)

- Angola’s departure leaves OPEC with 12 members

- At current production levels, Angola’s oil reserves are expected to last only 16 years, the shortest predicted duration in Africa and in OPEC

Angola becomes more pro-Western

Those domestic changes coincided with structural changes within OPEC, whose share of the global market shrank to 36 percent by 2022. In 2016, the group announced its Declaration of Cooperation: several non-OPEC countries, led by Russia, would coordinate production to support OPEC in its mission, giving birth to OPEC+. This has been the organization’s response to the shale revolution and the growing competition from the U.S.

The involvement of Russia proved controversial, in part because of Moscow’s perceived influence on OPEC+’s decisions, which has caused discontent among some of the more established members (mainly smaller producers), and partly because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused unease among members who have stronger ties with the West.

Despite its historical links to the Soviet Union, Angola has grown closer to the U.S. in recent years. On November 30, 2023 (which coincided with the last OPEC+ meeting for that year), President Lourenco met U.S. President Joe Biden in Washington, D.C. The U.S. leader described the diplomatic event as taking place “at a historic moment. Simply put, a partnership between Angola and America is more important and more impactful than ever.”

OPEC’s membership has changed since its formation in 1960, but departures have become more frequent in recent years, especially following the establishment of OPEC+.

The U.S. government is backing American private sector players who participate in significant economic projects across Africa, including the 1,300-kilometer-long east-to-west transportation corridor to connect Angola’s Lobito port on the Atlantic Ocean with Tanzania’s and Kenya’s ports on the Indian Ocean. President Lourenco described Mr. Biden as “the first U.S. president to change the cooperation paradigm between the U.S. and the African continent.”

Scenarios

Divergent forecasts

It is unlikely that Angola’s oil and gas output will suddenly boom in the next few years. Recent new projects have helped soften the production decline but have not been enough to reverse it. Experts differ in their longer-term forecasts. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects Angola’s crude oil capacity to fall by 0.35 million barrels per day to 0.82 million barrels per day by 2028 as operational and technical issues plague its high-cost, deepwater oil fields.

The agency adds that Angola’s declining performance will be one of the top factors behind the downturn in oil production between 2023 and 2028.

The Energy Information Administration (EIA), however, expects that many of the country’s larger projects will begin to bear fruit in the latter half of this decade and substantially increase the country’s production. Angola’s long-term production outlook will depend on companies’ ability to tackle technical challenges, and on market dynamics, price trends and government policies.

Most likely: OPEC+ faces more headwinds

Once outside the producers’ organization, Angola is free to pursue production plans without quota constraints. Even without being a member, Angola can still benefit from OPEC’s actions as the group seeks to prop up oil prices.

OPEC’s membership has changed since its formation in 1960, but departures have become more frequent in recent years, especially following the establishment of OPEC+. Indonesia left in 2016, Qatar in 2017 and Ecuador in 2020. Indonesia’s and Ecuador’s departures were linked to declining production, whereas Qatar wanted to focus on its more lucrative gas business. A diplomatic row with its Gulf Cooperation Council neighbors also played a role.

Shortly after Angola left, several African producers announced their commitment to OPEC. The reputational damage has therefore been contained as long as no other country follows suit, at least anytime soon. The unity among OPEC+ members and their discipline will be crucial to its ability to influence market conditions.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.