Middle East regimes challenge religious order, move toward modernization

In Egypt, Tunisia, and Saudi Arabia, leaders are chipping away at religious traditionalism to make way for the economic and social reforms peoples demand. Usually, the vehement backlash to such attempts has thwarted any momentum toward modernization in the Arab states.

In a nutshell

- Religious traditionalism has blocked modernization for centuries in Arab states

- Now, globalization is aiding leaders determined to bring reforms

- Religious institutions are likely to put up only moderate resistance

Generations of Muslim clerics, scholars and jurists have tried in vain to adapt the rigorous demands of Islam to the realities of the modern world. Now, the proverbial winds of change are sweeping through the Middle East. No country is immune to the impact of globalization: easier travel, the availability of information and worldwide social networks. From Egypt to Tunisia to Saudi Arabia, economic and social needs are challenging the old religious order. This time they just might prevail, because those spearheading the fight are leaders who believe reform requires a moderate interpretation of Islam.

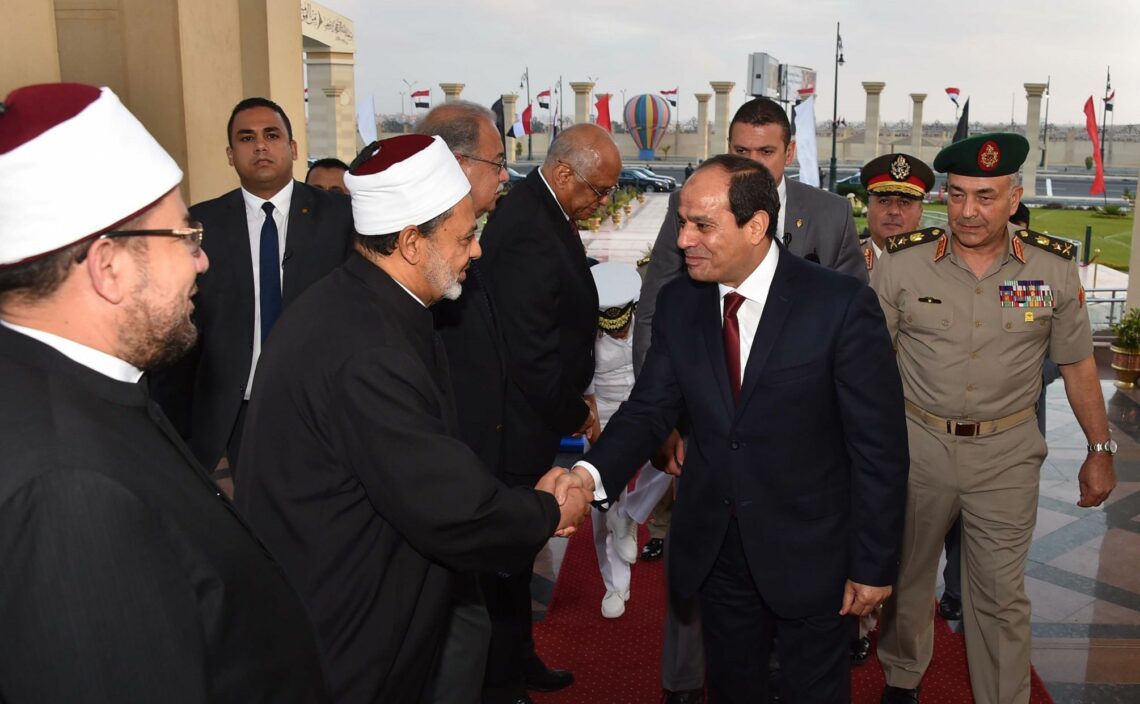

President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi in Egypt, President Mohamed Beji Caid Essebsi of Tunisia and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia are the most visible promoters of the trend, but it is being felt throughout the Arab world. The idea that fundamental change was needed – and wanted by the population – first gained traction during the so-called Arab Spring, a revolt largely fueled by the frustration of young university graduates and simple folk unable to find work. They demanded greater freedom and prosperity, and were the first to put into words Arabs’ yearning for a better life, free from the chains of tradition which made poverty, unemployment and illiteracy almost impossible to tackle.

Lacking experience or unity, these people allowed themselves to be swept aside by the long-entrenched and better-organized Muslim Brotherhood. In Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Morocco, parties linked to the organization won elections and, except in Morocco, established Islamist regimes. But people’s recently awakened desire for change was strong, and those regimes were toppled one by one. Nevertheless, the two conflicting trends – the dream of an Islamic revival and the hope of a brighter, unfettered future – are at the heart of today’s dilemma. The heads of state trying to implement reforms are devout Muslims, convinced change is necessary for their countries to succeed.

Bridging the gap

Toward the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the first attempts at bridging the gap between modernity and traditional Islam were made. It happened as Western culture began to penetrate into the Islamic sphere, with the French occupation of Tunisia in 1881, the British takeover of Egypt in 1882 and the establishment of Arab nation-states by France and the United Kingdom after World War I. (Some say it started much earlier in Egypt, with Napoleon’s conquest.) The result was a clash of civilizations in which the nascent Westernization had the religious establishment up in arms.

Attempts at modernization were met with near-universal resistance, but scholars kept trying.

The threat was not only political, military and scientific, it was almost a question of survival. Some of the greatest Arab scholars of the 19th century understood that a middle way had to be found. Such were Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, considered one of the founders of Islamic Modernism, and his disciple Muhammad Abduh, who later became the Grand Mufti of Egypt. They studied the fundamental texts of Islam – the Koran and Hadith – to determine how they could be interpreted in a way that would make it possible to accommodate some Western laws concerning the form of government and the status of women.

What made this task particularly difficult is that Muslims believe the Koran is the word of Allah, while the Hadith is a record of the words of the Prophet Muhammad. The endeavor was met with near-universal resistance, led by Al-Azhar, an institution that includes a mosque and the Sunni world’s most prestigious university. Still, other scholars kept trying. Their writings may have played a part in the decision of Kemal Ataturk, father of modern Turkey (Muslim though not Arab), to abolish the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924.

The Muslim Brotherhood was created in 1928 to combat these trends. Its aim was to block the penetration of Western values and to restore the Caliphate on the basis of Sharia law. Hassan al-Banna, who founded the movement, wanted Islam to return to the authenticity of the early days – those of the Prophet and of the four “rightly guided” caliphs who succeeded him. In his writings, he described Islam as encompassing politics, economy, science, sport and society – dominating all aspects of the life of man, society and nation.

Sayyid Qutb, the movement’s theologian, went one step further, making it legitimate to stigmatize “corrupt” Arab societies as infidels and forcibly bring them back to the “true” way. It was based on those teachings that all jihadi organizations, from al-Qaeda to Islamic State to al-Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria, were born. These movements pitted Sunni Muslims against other Sunnis, as well as against Shia Muslims led by Iranian Ayatollahs aspiring to impose their brand of caliphate on the Middle East. Hence the present turbulence in the region and its impact on the economy.

Egypt

In Egypt, Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi, elected president in 2014 after the ouster of Mohammed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, found himself battling an Islamic insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula while trying to implement far-reaching economic reforms. One of his first steps was to visit Al-Azhar, where he made a speech calling for radical Islamic rhetoric to be toned down. Convinced that education was the key to reform, President El-Sisi also ordered Egypt’s Ministry of Education to expunge passages encouraging violence and calling for jihad from elementary and secondary schoolbooks.

Some of these texts were gruesome tales of massacres and destruction, such as the campaigns of Egyptian Sultan Salah ad-Din and Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi, who conquered North Africa. Of the many disparaging references to the Jews, a few were taken out. Al-Azhar remains reluctant to follow suit, and tensions between the president and the institution still run very high. However, Al-Azhar’s recent pronouncement condemning sexual harassment of women, something not explicitly addressed in the Koran, offers tacit support for the president’s attempts to liberalize attitudes on women’s issues. President El-Sisi has appointed women to the head of several governorates, including, for the first time ever, a Copt.

Tunisia

Mohamed Beji Caid Essebsi, founder of the secular Nidaa Tounes party, in 2014 became the first Tunisian president to take office after free elections. His country has been at the forefront of a battle for women’s equality, begun by former President Habib Ben Ali Bourguiba (1957-1987), who had forbidden polygamy, a practice accepted in Islam. In August 2017, the Tunisian parliament passed a law condemning violence against women. Egypt, Morocco, Lebanon and Jordan then passed similar laws, which among other things did away with the practice of acquitting rapists who were ready to marry their victims.

Later that year, President Essebsi proposed amendments to the country’s inheritance law that would give women equal rights to men. The move was immediately condemned by Al-Azhar, which claimed that family matters, including inheritance, had been set down in the Koran and could in no way be subject to interpretation or amendments. Undeterred, the Tunisian president declared on August 13, 2018 – Tunisian women’s day – that he stood behind the amendments, which the parliament has begun examining. His government has also overturned a law banning Muslim women from marrying non-Muslims, though plenty of resistance to such unions remains.

In 2017, he appointed an “Individual Freedoms and Equality Committee” to prepare a reform project “in accordance with the requirements of the Tunisian Constitution of 2014 and international human rights standards.” One of the committee’s first recommendations was to decriminalize homosexuality, or at least treat it with greater leniency. Al-Azhar regularly condemns similar suggestions.

Saudi Arabia

Many eyebrows were raised in Arab countries and in the world at large when the winds of change touched Saudi Arabia, home of Islam’s two holiest sites, in Mecca and Medina. Wahhabism, perhaps the most stringent form of Islam, is strictly enforced in the kingdom. The tradition goes back to the 18th-century pact between Muhammad bin Saud (considered the founder of modern Saudi Arabia) and Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a preacher bent on purging Islam of impurities.

MbS let women attend concerts in stadiums, then decided to reopen cinemas, which had been closed for decades.

Here, too, the first reforms concerned the condition of women, traditionally treated as second-class citizens and often needing the permission of a male relative to engage in various activities. The late King Abdullah (2005-2015) allowed women to participate in local elections and to take part in the Olympics. Both moves were harshly criticized by the religious establishment. He also tried to curb the religious police (often called the morality police), replacing its head with a more moderate cleric.

King Abdullah’s nephew, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (known as MbS), has set in motion far-reaching reforms. MbS let women attend concerts in stadiums, then decided to reopen cinemas, which had been closed for decades, also allowing women to attend. His most talked-about decision was allowing women to drive.

He further reduced the powers of the religious police, fired several extremist clerics and made it clear that he would not tolerate opposition to his reforms. In presenting his “Vision 2030” program, he pledged a return to moderate Islam. His plans include establishing a huge futuristic city called Neom, on the Red Sea, in the northwestern part of the country, with its own judicial system and where women will be allowed to wear bikinis at the beach.

The religious establishment is seething, but so far has refrained from open conflict with the political leadership.

In the past, far milder measures – such as allowing pictures of women in the press – led to violent protests from local members of the Muslim Brotherhood. In 1979, armed extremists burst into the sacred Grand Mosque in Mecca and took hostages. Hundreds of militants and many members of the Saudi security forces were killed in the repression that followed. Publishing pictures of women was banned and cinemas were closed. Today, the religious establishment is seething again, but so far has refrained from open conflict with the political leadership.

Slow progress

All Arab leaders are grappling with the same problem: They know that the future of their countries hinges on successfully carrying out economic and social reforms. They also know that they need Western expertise and investment. Often, their countries’ poor human rights records, especially the restriction of women’s rights, is a stumbling block to achieving these goals. These leaders have great respect for the faith of their fathers, but want to do away with the archaic rules that hinder progress. It has been done in the past. Banking systems based on levying interest on loans directly contradict Sharia law as it is usually interpreted. Yet all Arab states take part in the global finance system, even though most of them have constitutions that declare Sharia as the main source of legislation.

The most probable scenario is that progress will be steady but slow. Leaders will proceed cautiously, reform after reform, law after law, chipping away at restrictions. Overall, they will meet only moderate resistance from religious institutions.

Al-Azhar will be the main exception. This venerable institution, which sees itself as the sacred keeper of tradition, will closely watch developments and will not tolerate attempts to find new interpretations of Sharia and its sources, which have been faithfully transmitted through generations since they were handed to the people 1,400 years ago. However, necessary reforms will be quietly condoned.