What does the rise of Javier Milei mean for Argentina?

The upstart right-wing populist is the presidential front-runner. He appeals to young, alienated voters weary of the Latin American nation’s chronic economic woes.

In a nutshell

- Three presidential candidates will vie in the October 22 elections

- Voters will also choose a new congress in the same contest

- No single party is likely to emerge with a legislative majority

Amid ongoing economic and security problems, far-right political outsider Javier Milei won the most votes in Argentina’s open presidential primaries on August 13. The libertarian who pledged to dollarize the economy, close the central bank, radically cut government spending and privatize state-run companies is now the front-runner in the October 22 elections. Whether he or a candidate from one of the country’s traditional political coalitions ultimately wins, the new leader will face a series of challenges to resolve an economic crisis.

Unexpected primary results

The libertarian Mr. Milei earned 30 percent of the vote in the country’s compulsory open primaries, with his political party Freedom Advances (La Libertad Avanza or LLA) also securing the highest number of votes. He and his party shocked many pollsters by outperforming the country’s two traditional political coalitions. The center-right opposition coalition Together for Change (Juntos por el Cambio or JxC), earned 28.3 percent, while the ruling center-left Union for the Homeland (Union por la Patria or UxP), came in third at 27.3 percent. Mr. Milei claimed victory in 16 of Argentina’s 24 provinces, defeating traditional Peronist strongholds.

All parties must participate in the primaries, with winners advancing to the general election. In this way, they offer a chance to measure party strengths ahead of the general elections while simultaneously resolving internal battles.

The ideological right dominated all tickets. Not only was Mr. Milei successful, but hardline former security minister Patricia Bullrich defeated the more moderate Buenos Aires Mayor Horacio Rodriguez Larreta on the JxC ticket (17 percent to 11.3 percent), while Economy Minister Sergio Massa defeated labor activist Juan Grabois on the UxP list (21.4 percent to 5.9 percent). The results mean the presidential election will be a three-way race among Mr. Milei, Ms. Bullrich and Mr. Massa.

Facts & figures

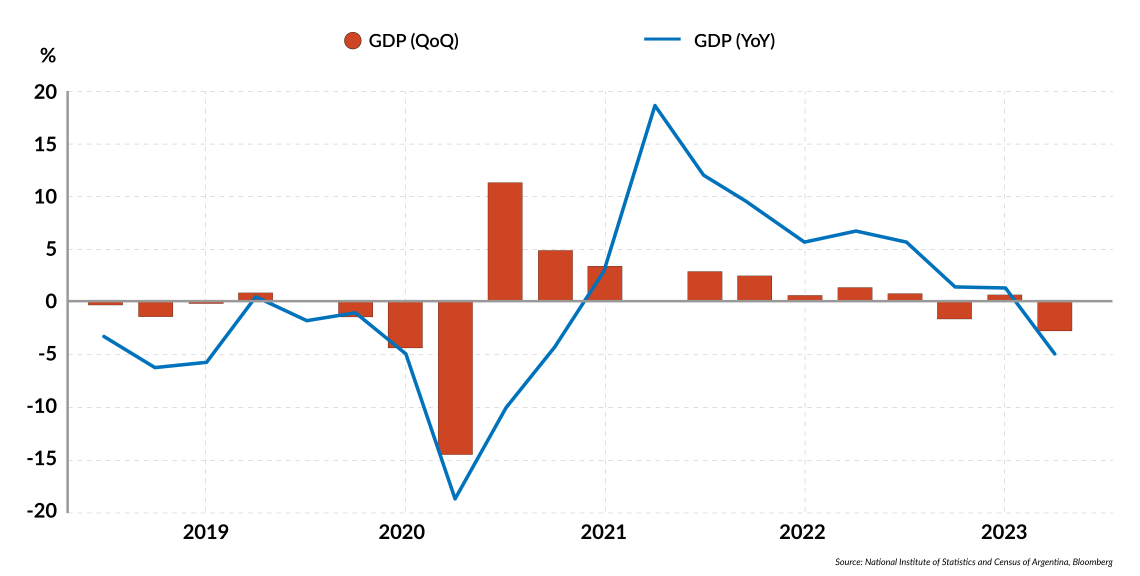

Argentina’s economy heading for recession

A country facing predicaments

The primary election campaign focused on economic and security issues. Inflation in Argentina, a country of 46 million people and a gross domestic product expected to top $600 billion in 2023, has soared to triple digits. Amid the hardship, violent crime has increased, prompting security concerns, while the government of Alberto Fernandez has done little to confront public sector corruption.

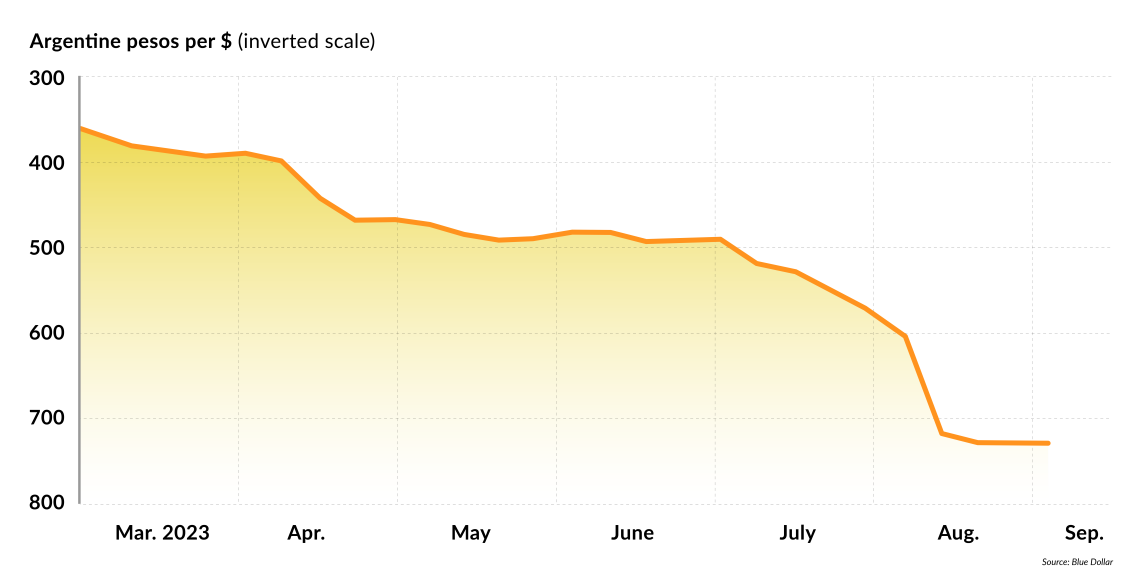

Most worrying for the next president is the state of the economy. The monthly inflation rate climbed to 12.4 percent in August 2023, the highest monthly figure since 1991, bringing the annual rate to 124 percent. Depreciation has also caused the peso’s black-market value against the dollar to fall by half this year, from roughly 350 to the dollar to 700, as Argentines hoard dollars or quickly spend their pesos. The surge in the cost of living has also pushed poverty past 40 percent, while a severe drought has further damaged the economy. At the same time, the Fernandez government battled to salvage a $44 billion deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) amid these problems and evaporating international reserves.

Security concerns are also rising. Although Argentina remains one of the safest countries in Latin America, violence tied to narcotics trafficking has increased visibly in some places, including the city of Rosario and some parts of Buenos Aires, and several high-profile murders have exacerbated citizens’ fears. Understandably, voters are in a sour mood – and hungry for a political outsider.

Facts & figures

Argentine peso craters against U.S. dollar on the country’s black market

Who is Javier Milei?

Mr. Milei is an outspoken libertarian economist and self-described “anarcho-capitalist” who portrays himself as an outsider uniquely positioned to solve Argentina’s problems. Like former presidents Donald Trump in the United States and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, he combines social conservatism with anti-system populism; his anti-political rhetoric is calculated to both entertain and shock voters. Among other positions, he maintains that selling human organs should be legal, climate change is a “socialist lie” and sex education a ploy to destroy the family. In economic policy, he hopes to officially adopt the U.S. dollar for Argentina’s economy and dramatically cut government spending besides abolishing the central bank.

Like presidents Trump and Bolsonaro, Mr. Milei has successfully articulated societal dissatisfaction with traditional politicians and nimbly used social media to amplify his message. In this sense, his primary success reflects a protest vote against the political establishment. His radical ideas appeal primarily to young, alienated Argentines who believe that only profound upheaval can lead the nation to better times. Indeed, his attractiveness to voters may have less to do with specific policy proposals than the anti-system figure that he cuts. Worryingly for Argentina, he also has an authoritarian streak: the candidate suggested that a former presidential aide should be beheaded and has pushed electoral conspiracy theories.

Mr. Milei’s primary success has not resulted in rhetorical moderation. In early September, he verbally assailed Pope Francis, calling him an “imbecile who defends social justice,” a “son of a bitch preaching communism” and “the representative of the evil one on Earth” on social media. He then reiterated these attacks in a wide-ranging interview with conservative U.S. talk show host Tucker Carlson the following week, in which he also praised Mr. Trump, denounced “gender ideology” and the legalization of abortion. He also repeated his claim that climate change is a socialist hoax.

Mr. Milei’s vice presidential running mate, Victoria Villarruel, held an event that paid tribute to the “victims of terrorism” during Argentina’s dictatorship (1976-1983) – meaning the victims of left-wing guerrillas who fought the military junta rather than the far greater number of civilian victims of the junta itself. Ms. Villarruel is a former lawyer for soldiers accused of atrocities during the dictatorship and has a long history of publicly defending military officers charged with crimes against humanity.

These spectacles only raised Mr. Milei’s numbers in the polls.

More by John Polga-Hecimovich

Central America’s dysfunction grinds on

President Lasso’s fight for survival

Peru’s cycle of instability continues

Facts & figures

Argentina's economic debacle is long in the making

Argentina has suffered decades of economic mismanagement and repeated economic crises. It has also defaulted on its sovereign debt nine times in its history, most recently in 2020 as it faced economic contraction, runaway inflation, and a hard-currency squeeze during the coronavirus pandemic.

Things are somehow worse today. The country faces triple-digit inflation rates and is the world’s largest debtor to the International Monetary Fund, with $46 billion in outstanding debt.

These problems are the consequence of structural limitations as well as populist policy choices aimed at short-term political gains at the expense of long-term economic stability. Chief among these is unsustainable government spending, a historical legacy from the mid-20th century. Argentina has a large public sector and deeply subsidized healthcare, energy, universities and public transportation, all of which the government can only afford to fund through deficit spending or the printing of more pesos. This, in turn, exacerbates inflation.

Because of this reality, Argentines have long bought and saved dollars to counteract the loss of the peso’s purchase power. Moreover, government currency controls which limit citizens to purchases of just $200 per month create a thriving black market for dollars at a less preferential floating exchange rate. Multiple exchange rates and a currency nobody wants to buy or save thus create macroeconomic hurdles for savings, investment and growth.

Lastly, the country’s weak export sector has been hurt by the effect of drought on agricultural commodities. To boost exports, the leftist government of Alberto Fernandez has devalued the peso, then attempted to offset its effect through a raft of new economic measures, including an increase in pension payments. Of course, these measures will only further contribute to the pernicious cycle.

Congressional and presidential elections combined

The country’s congressional and presidential elections will be held on October 22. To win in the two-round system, presidential contenders need 45 percent of the vote, or a minimum of 40 percent with a 10-percentage point lead over the runner-up. If no one reaches these thresholds, a second-round runoff will take place on November 19. Given the vote breakdown of the three main coalitions in the primaries, the country’s future leader will likely be decided in the second round.

Almost any run-off combination is possible. Based solely on the August results, there is a high probability that Mr. Milei will win the most votes in October and end up contesting the runoff with Ms. Bullrich. However, there is no guarantee that Ms. Bullrich will be able to make inroads among centrist voters within and beyond her JxC coalition, potentially helping Mr. Massa reach the second round. Moreover, post-primary public opinion polls indicate that Mr. Milei has gained support at Ms. Bullrich’s expense.

Whoever advances, the second round will spotlight the candidates’ significant warts. Now that Mr. Milei has shown he is a serious contender, voters alarmed by his extremist positions and rhetoric may turn out in higher numbers than in the primaries. Voters would also be more likely to coalesce around his opponent, either informally or via a cross-party alliance. At the same time, polls indicate that Mr. Massa also possesses an upper limit of backing, with many voters expressing an unwillingness to ever vote for him based on his leadership as economy minister during the country’s worst inflationary crisis in decades.

Scenarios

No candidate will find it easy to govern as president. Projections from La Nacion suggest that no coalition is close to fielding a congressional majority. The newspaper puts Ms. Bullrich’s JxC at 107 out of 257 seats in the Chamber of Deputies (41.6 percent) and 26 out of 72 seats in the Senate (36.1 percent), Mr. Massa’s UxP at 94 (36.6 percent) and 33 (45.8 percent), and Mr. Milei’s LLA at a mere 40 (15.6 percent) and 6 (8.3 percent).

As a result, whoever wins the presidency will find themselves in the unenviable position of engaging in legislative horse-trading to build a working governing coalition – a particularly tough proposition amid the country’s polarized politics. Mr. Milei, a political neophyte with radical views and what will likely be the weakest legislative backing of the three candidates, would fare the worst and would be the most likely to attempt to govern through executive decrees and plebiscites.

This suggests that Argentina’s next leader will be hard-pressed to drag the country out of its crises without significant political and social pushback.

Scenario 1: Milei discards the status quo

Mr. Milei’s success in the primary has already upended Argentine politics, the partisan establishment and the logic of the two-party system. For a country whose politics have been dominated by two competing ideologies, Peronism and Radicalism, a victory in November by a political outsider would cause a shock wave.

All three candidates have promised economic reforms, but Mr. Milei’s proposals are the most radical and the least likely to be successfully implemented. These include drastic cuts in government spending, the privatization of public companies that are a burden on the state, increased private investment, an overhaul of the public healthcare system, cuts in labor taxes and the elimination of tariffs on imports of strategic inputs and capital goods, all with the promise that Argentina would not default on its debt to the IMF.

More radical proposals would still be harder to achieve – and potentially much more damaging. On the one hand, dollarization would temper inflation and end exchange-rate swings so damaging to foreign trade. At the same time, Argentine banks and households would need a float of dollars to get up and running, which the government cannot provide. Indeed, Argentina even finds it difficult to service its debts to the IMF.

Beyond economics, Mr. Milei’s security policy would incorporate elements of the mano dura (iron fist) policies that have proven popular in El Salvador under Nayib Bukele. In fact, the candidate has already said he would place his hardline vice president, Ms. Villarruel, in charge of the police and armed forces.

Internationally, a Milei administration would align itself with the West – especially the U.S. and Israel – although it remains to be seen how a Joe Biden government would receive Mr. Milei. Pushing back against China, as the candidate suggests, would be harder: Argentina’s precarious financial situation makes the currency swap line with China indispensable for Argentina’s economic survival, and China also represents Argentina’s largest export market. Nonetheless, Mr. Milei could distance Argentine geopolitically from China by withdrawing its candidacy from the BRICS group. In the rest of Latin America, Mr. Milei would not currently enjoy the company of any like-minded governments, blunting his regional ambitions.

Scenario 2: A law-and-order Bullrich government

A Bullrich presidency would adhere to a center-right program. As ex-President Mauricio Macri’s security minister (2015-2019), Ms. Bullrich defended strict law-and-order policies and adhered to right-wing economic talking points on the campaign trail. She would retain the peso, introduce a unified and free exchange rate and renegotiate Argentina’s existing agreement with the IMF. She has already named the economically orthodox Carlos Melconian as her economy minister should she win the election. While her government would pursue reduced public spending, it would fall short of Mr. Milei’s extreme cuts. Ms. Bullrich has also pledged to improve healthcare and education and crack down on the drug trafficking that contributes to the country’s violence.

Given her coalition’s ideological position between the far-right LLA and the Peronist UxP, her government would have the easiest time building a working legislative coalition. It would also be an ally of the U.S. and the West, and would be likely to withdraw from BRICS consideration. Ms. Bullrich is a neoliberal and would continue Argentina’s role in the regional trade bloc MERCOSUR while also attempting to pursue bilateral free trade agreements with other countries.

Scenario 3: Continuation of Peronism under Massa

A Massa-led government would have to defy the odds to reach power: most Argentines blame the Peronist Party for the country’s economic situation, and President Fernandez is an unpopular incumbent. The UxP list finished third in the primaries.

However, Mr. Massa also possesses some advantages. While Mr. Milei and Ms. Bullrich both compete for votes on the right, Mr. Massa is alone on the left. Moreover, he should be able to count on the Peronist party machinery to deliver votes. As economy minister, he also controls economic levers that may help him. Although the IMF called for “expenditure controls” following the disbursement of a $7.5 billion loan tranche on August 23, Mr. Massa announced new economic measures aimed at mitigating the impact of the country’s crisis on August 27, declaring that “the main objective is for every economic sector to somehow receive support from the state.”

Nonetheless, and somewhat paradoxically, Mr. Massa maintains a good relationship with the IMF and Washington and is seen by markets as the most economically pragmatic of the three candidates. Although he is a centrist Peronist, his government is the least likely of the three possible to cut public spending and, despite declarations to the contrary, the most likely to default on the country’s significant debt. His government would also be the most pro-China of the three candidates, with foreign policy largely representing a continuation of the current government’s.