President Lasso’s fight for survival

President Guillermo Lasso could be impeached over corruption allegations. Ecuadorian politics face uncertainty as the National Assembly weighs in.

In a nutshell

- Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso faces impeachment

- Crime, corruption and a failed referendum have eroded his approval ratings

- If he survives, the leader will find it near impossible to govern

Ecuadorian politics is once again steeped in uncertainty. On March 29, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court approved a motion of impeachment submitted against President Guillermo Lasso by deputies from ex-president Rafael Correa’s Union for Hope coalition (UNES). Mr. Lasso is accused of having been aware that his close associates were involved in a corruption scheme embezzling funds from state companies. The opposition-dominated National Assembly now has up to 45 days to complete the impeachment process against the president. Removing him will require the votes of at least two-thirds of the chamber, or 92 of the 137 legislators.

Whether President Lasso survives the impeachment vote, is removed by the National Assembly or dissolves the government and calls for snap elections, the Ecuadorian government will continue to struggle with rampant insecurity and social opposition.

Lasso’s weak mandate

The right-wing Guillermo Lasso entered office with a weak mandate. He earned only 19.7 percent of the first-round vote in the 2021 elections, the lowest share of first-round support for an eventual winner in Ecuadorian history and just 0.3 percentage points ahead of the third-place finisher. Moreover, he defeated Andres Arauz of UNES in the runoff election with fewer votes than he earned while losing the 2017 race – suggesting that his victory was partly due to anti-Correa sentiment. Finally, his Creating Opportunities (CREO) party earned only 12 seats in the 137-member National Assembly, meaning that governance would be predicated on the president’s ability to forge and maintain legislative coalitions with parties across the ideological spectrum.

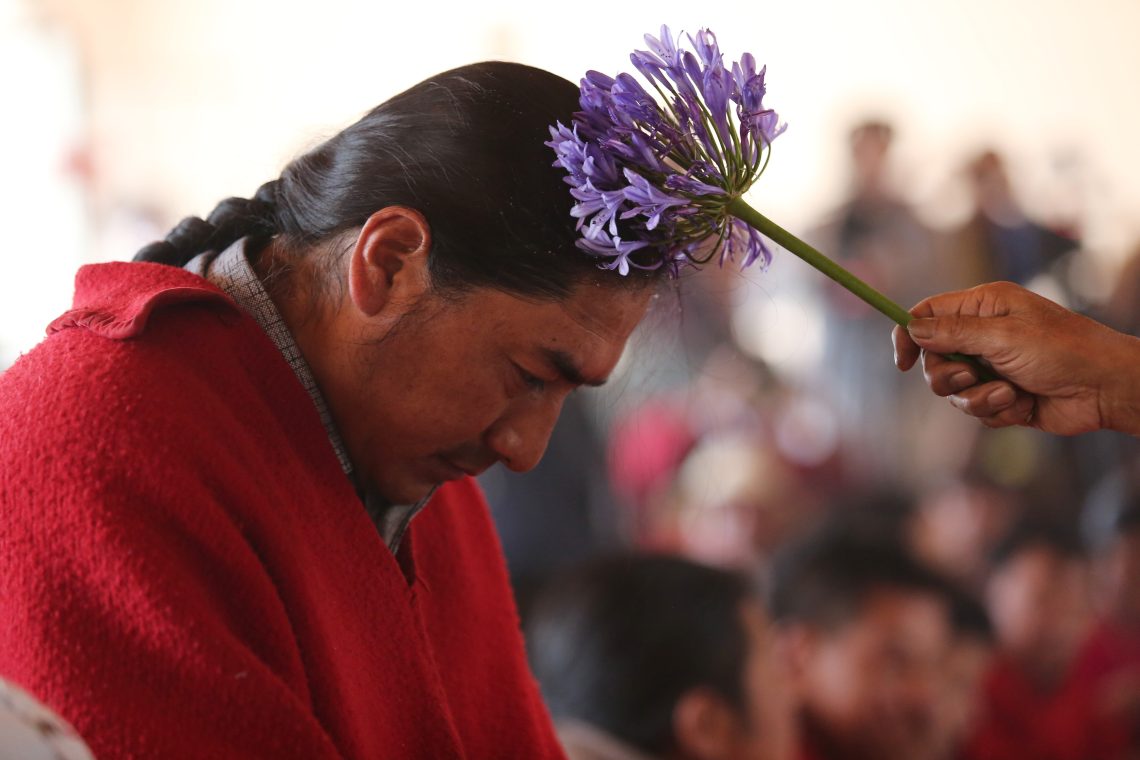

Predictably, he faced threats to his survival almost immediately. In December 2021, just six months after taking office, the president comfortably survived a first impeachment motion related to offshore accounts revealed in the Pandora Papers. However, amid countrywide protests spearheaded by Leonidas Iza and the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) against a rise in the cost of living as well as the country’s dependence on extractive industries, the National Assembly debated another impeachment motion which moved to a floor vote in June 2022. This time, the president survived with only 12 votes to spare, with 80 deputies voting for his removal, 48 voting against, and nine abstentions. The indigenous Pachakutik party, which held the balance of power in the assembly and had been aligned with the government, voted almost unanimously against Mr. Lasso.

The two biggest thorns in the president’s side have been the CONAIE, a well-organized and influential group with a long history of influencing politics from the streets, and pro-Correa political elites, including Correa’s left-wing Citizens’ Revolution (RC) party. Both CONAIE leadership and pro-Correa politicians in the National Assembly have called for Mr. Lasso’s removal, with RC presenting the impeachment motions.

Crime, corruption and a failed referendum

President Lasso has among the lowest approval ratings of any Latin American president, driven in part by food and fuel price inflation, which triggered the June 2022 protests led by the CONAIE. However, a drastic rise in crime as well as corruption allegations against those close to the president have further weakened him.

More by John Polga-Hecimovich

Peru’s cycle of instability continues

Postelection Brazil: The house is still divided

China’s evolving economic footprint in Latin America

The security situation has been especially troublesome. Since late 2020, the fragmentation of criminal gangs and competition over valuable narcotrafficking routes have resulted in a rise in crime and prison and street violence. Since 2022, there have been bombings in Guayaquil, the country’s main exit point for cocaine trafficking, and kidnapping and homicide rates have increased dramatically across the entire country. The government has few resources to stop drug trafficking organizations’ increasingly sophisticated and aggressive tactics. Although the president has repeatedly authorized emergency decrees and states of exception in Guayas Province and elsewhere, there is little evidence that these measures have made a noticeable difference. Moreover, given that improving security was one of Mr. Lasso’s campaign promises, the rise in homicide and criminality is particularly damaging to his approval.

Compounding the president’s problems, Mr. Lasso has faced two corruption scandals, both of which served as fodder for and precipitated the impeachment vote. In the so-called Caso Encuentro (“Encounter Case”), the president’s brother-in-law, Danilo Carrera Drouet, was accused by the digital media outlet La Posta of involvement in a corruption racket at state companies. Although the president initially denied the existence of money skimming in state enterprises, he later backtracked and fired the CEOs of 13 state companies to restore public trust. In addition to this investigation, the attorney general’s office is also carrying out a second probe into state oil company Petroecuador, which resulted in a prosecutorial raid of the CEO’s house and his subsequent resignation. While President Lasso himself has not been accused of direct involvement in these cases, the attorney general’s report claims that he obstructed investigations into his government.

Facts & figures

Muerte cruzada

Muerte cruzada, or “crossed death,” is a political mechanism in Ecuador’s constitution that allows the president to dissolve the National Assembly and call for new legislative elections under specific circumstances. Conversely, the National Assembly can also dismiss the president under certain conditions. This mechanism was designed to resolve situations of severe political deadlock or crisis between the executive and legislative branches. The term “crossed death” refers to the mutual ability of both branches to dissolve each other, prompting new elections and a potential reshuffling of power.

Faced with legislative gridlock and this series of setbacks, the president called for an eight-question national referendum to pursue major changes to the role of the armed forces in public security, the size of the national assembly, and the appointment of public officials via constitutional amendments. Like his predecessors Rafael Correa and Lenin Moreno, he hoped that public discontent with the legislature would result in victories for his policies which would in turn act as a vote of confidence and boost his sagging fortunes. However, this gambit failed: voters struck down all eight proposals, and in the concurrent local elections, candidates backed by Mr. Correa won mayoral races in Quito and Guayaquil, the country’s two most populous cities. These results further reduced the president’s political capital and legitimacy.

Scenarios

Regardless of what happens in the short term, ex-president Correa’s RC is poised to return to power, either through early elections as a result of muerte cruzada or scheduled elections in 2025.

Ecuadorians appear nostalgic for correismo, just two years after rejecting Correa-backed Andres Arauz in the 2021 elections. The February local election results showed a resurgence of RC, a key pillar in UNES, and suggest a public tired of Mr. Lasso’s brand of neoliberalism. If an RC candidate comes to occupy the presidency, the goal would be to upend the status quo. Mr. Correa has already said that he would like to pursue the installation of a constituent assembly that would avoid overcoming the controls of the Constitutional Court judges.

Whoever emerges victorious from this protracted legislative-executive struggle will have to contend with a restive indigenous movement as well as challenging public security concerns.

Lasso falls and Borrero muddles along

After the May 9 vote in which 88 deputies voted in favor of moving ahead with the impeachment process – just four short of the 92-vote threshold – the most likely scenario is Mr. Lasso’s removal through impeachment or non-reelection via muerte cruzada. If the president opts for the latter, it is an indication he cannot muster enough willing deputies to stave off the legislative vote and is turning to the only tool that he retains. Given Mr. Lasso’s low public approval, the move would almost certainly fail, and the country’s politics would be likely to swing back to the left. This is because, at present, Mr. Correa’s RC is in the most beneficial position to enlarge its legislative plurality and perhaps even achieve a majority, while center-right parties bear the brunt of public disapproval for President Lasso.

If the president leaves office via impeachment, the constitutional successor would be Vice President Alfredo Borrero, a neurosurgeon and political independent. This is the least damaging and most advantageous option for the Democratic Left (ID), The Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement (MUPP), and Social Christian Party (PSC), all of whom would see their legislative benches shrink under new elections. As with the interim presidencies of Fabian Alarcon (1997-1998), Gustavo Noboa (2000-2003), and Alfredo Palacio (2005-2007), Mr. Borrero lacks a mandate and a legislative bloc and would most likely focus on muddling along until the 2024 elections. Nonetheless, the PSC has a relationship with him, and government priorities would be likely to reflect this right or center-right orientation.

It is also possible that both the president and vice president are removed, in which case the presidential successor would be National Assembly President Virgilio Saquisela, an ambitious legislator who has switched parties several times and was elected as part of a small regional political movement. He would likely govern with some combination of RC and PSC deputies.

Lasso survives but governability declines

The second-most likely outcome is that President Lasso will be able to cobble together sufficient support to survive the impeachment attempt. His team has been busy constructing a legislative shield through the distribution of pork and public appointments, such as provincial governorships, and he seems to have placed a bet on finding the 46 votes among a combination of legislators from his own party as well as others from across the ideological spectrum. He also retains the support of the military high command, an important institutional ally in past governability crises, even without direct participation. Sufficient legislative support would also obviate the need for muerte cruzada, a risky electoral option for someone with such low popularity and recent losses at the polls.

However, regardless of whether Mr. Lasso resists the temptation to invoke muerte cruzada and survives this impeachment vote, the president’s medium-term political future is not encouraging. His unpopularity with the voting public, contentious relationship with the CONAIE and fierce opposition in congress raise serious questions about his ability to govern – and to finish the final two years of his term. This will be especially true if the impeachment vote results in the president’s narrow survival. The National Assembly has only passed three executive proposed bills in President Lasso’s two years in office, and he will be hard-pressed to build any type of workable legislative majority and improve upon that tepid output. Instead, he will have to temper his ambitions and operate on the margins largely through his unilateral powers.

Furthermore, stiff resistance to the president’s policies shows little sign of abating. The vultures will circle in the form of judicial investigations into corruption allegations and most likely, more street protests led by the CONAIE, suggesting the strong possibility of yet another attempt at removing him from power.

Lasso survives and governability improves

The least likely scenario is that Mr. Lasso survives and leverages the impeachment process or a successful reelection after muerte cruzada into a renewed mandate to pursue an ambitious policy agenda. This optimistic situation would only occur if voters were swayed by President Lasso’s mano dura (firm hand) policies, such as the recent decree authorizing civilians to carry and use firearms in self-defense and believe that he is a better alternative than his vice president or another leader. This seems improbable. Even if Mr. Lasso is successful at building legislative support, this outcome will not reflect a rise in his political capital but the instrumental nature of executive-legislative negotiations in times of crisis. Most presidents who survive impeachment processes in Latin America find their positions weakened vis-a-vis opposition parties and their agendas beholden to their new legislative allies. There is little evidence to suggest that President Lasso will fare differently.