President Fernandez tries to take control

Just eight months into his tenure, the new president of Argentina, Alberto Fernandez, has been thrown a trio of challenges. In the coming months, he must deal with the public health crisis, revive a deeply damaged economy, and consolidate power in his own fractured coalition.

In a nutshell

- A strict quarantine saved lives, but the economy has suffered

- President Fernandez now faces challenges concerning the country’s finances

- An intraparty faction led by a popular predecessor is a threat

It has been only eight months since the government of Alberto Fernandez assumed office in Argentina, and in that time, his program has already been thrown off-kilter by pandemic-related challenges. Today, Fernandez faces three challenges in the weeks and months ahead: to deal with the public health crisis; to prepare for an economic recovery following the abrupt decline in economic activity during the shutdown, which began under the previous government and which has brought the country to the brink of default; and, last but not least, to resolve the political fissures in his own party that are compromising his ability to govern.

Alberto Fernandez won the October 2019 elections with 48 percent of the vote against 41 percent for his opponent, the incumbent Mauricio Macri. The relative split between the two political forces is reflected in the chamber of deputies, where neither has a majority. This balance reflects the realignment of political forces that began in 2015 in which two coalitions organized into the parties’ struggle for power.

These two are the Justicialist Party, a Peronist party; and Together for Change, an alliance of the conservative Republican Proposal, the left-leaning Radical Party, and the Civic Coalition, which brings together a small group of personalist leaders of the left and right. Relative party stability has allowed the channeling of political, economic and social conflicts through institutions, in contrast to many of the country’s neighbors, which experienced unsettling social upheavals even before the pandemic hit.

Although there is significant polarization in the current debate, there are no significant anti-system forces, and the political conflicts (however marked) have not threatened the democratic regime installed 37 years ago after decades of military dictatorship and instability.

Facts & figures

We have a deal

Details of the August 4 debt deal between the Argentine government and its creditors:

- $65 billion in private foreign bonds will be restructured after months of talks

- Three creditor groups, led by the U.S. investment firm BlackRock, banded together for the negotiations

- Terms of the deal indicate a recovery value of around 55 cents per dollar

- Argentina still owes another $44 billion to the International Monetary Fund, with new talks pending

Pandemic trade-off

Confronted by the same dilemma facing every government to balance human life against economic activity, Argentina chose human life, and decreed a strict national quarantine – 90 points on the Oxford University Stringency Index. One month later, the quarantine was relaxed in most of the country but remained stringent in the federal capital of Buenos Aires and the surrounding metropolitan area, which produces 75 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The swift and clear action by the government won broad public approval and, in a country not known for its social discipline, widespread acceptance. The early response also bought time to restore the country’s public and private health sectors, which had been underfunded for years. Fortunately, compared to other countries in the region, Argentina has excellent human resources in the medical system and has its own pharmaceutical industry, which allowed for a better pandemic response.

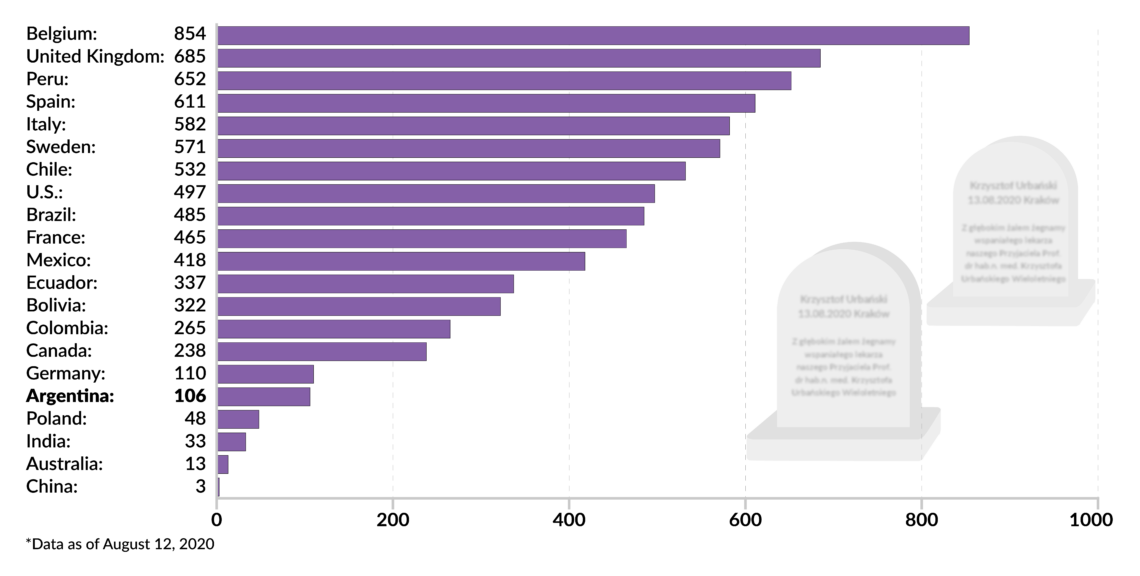

Early and effective action meant that the government could deal with pockets of poverty and vulnerability in the interior provinces. Although the total number of cases has been (and continues to be) high, the mortality rate has been very low. As the table below indicates, Argentina’s death rate has been better than many OECD countries as well as many of its neighbors in South America.

Facts & figures

This relative success, together with the country’s established professional medical core and its pharmaceutical industry, has led to it being chosen to participate in phase 3 testing of the vaccine being prepared by Pfizer and the German firm BioNtech. Argentina prioritized health over the economy, acting quickly and resolutely to contain the pandemic. But this emphasis on the public health dimensions of the crisis will complicate the country’s economic recovery.

In the face of the pandemic, the government put in place a series of compensatory payments to the most vulnerable. Over 9 million people received $150 per month (the active population of the country is nearly 21 million), and salaried workers received subsidiaries so that their employers could continue to employ them. Measures to promote the economy more broadly were delayed for several months.

Economic pressures

The Argentine economy was in a precarious situation before the pandemic; between 2011 and 2019, GDP fell 1.3 percent annually. Exports were mixed, primarily because prices for raw materials and manufactured agricultural goods were weak. This was compensated in part by an increase in manufactured industrial goods and energy exports. Still, exports lacked dynamism, coming in at $85 billion in 2011 and $65 billion in 2019.

The Argentine economy has long suffered from low productivity. Sectoral oligopolies are entrenched, and the high tax rate and rigid labor market do not generate incentives to increase private investment. Moreover, Argentina is a closed economy where a potential decline in tariffs would destroy a large segment of the small- and medium-sized businesses, the firms that provide the largest portion of employment in the private sector.

Sectoral oligopolies are entrenched, while high taxes and a rigid labor market do not encourage investment.

The damage to the economy soared during the strict April quarantine, with a nearly 26 percent decrease in economic activity. To get a sense of the severity of this decline, we can compare it to the severe depression of 2001 during which there was a cumulative decline of 21 percent. The preexisting weakness of the Argentine economy served to accentuate the economic damage caused by the pandemic, damage far greater than that suffered by any of its neighbors as a result of the pandemic. The World Bank estimates that the Argentine economy will shrink by 9.9 percent this year and rebound by 4.5 percent in 2021. In this scenario, unemployment will reach 10 percent (in a country where new dismissals have been prohibited in an attempt to keep the rate low) and poverty will reach 50 percent of the population.

To complicate matters further, Argentina has a history of high inflation. Over the years, it has chosen to print money to get out of short-term economic problems. As part of the high-wire act, to print enough money to govern without letting inflation get out of hand, the government maintains three different exchange rates, which it maintains through a complicated set of regulations, known locally as the Cepo.

With inflation running at about 50 percent on an annualized basis, the Argentine government has been renegotiating its international debt of about $323 billion – which is just under 90 percent of the country’s GDP. President Fernandez opened talks with the creditors as soon as he came into office, as his advisors judged that the country could not pay the interest on the debt in 2020 or 2021. About 40 percent of this debt ($66 billion) is held by private investors, 22 percent by international financial institutions, and the rest is owed to public institutions in Argentina.

The weakness of the Argentine economy accentuated the damage from the pandemic.

By early August, the president achieved that goal, and must now turn his focus to the economic recovery. In addition to the arduous economic negotiations, international politics slipped into the mix. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) had been supportive of Argentina in its efforts to renegotiate its debt, even going so far as to approve an offer made by the government of Argentina to the private creditors.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government – whose support Mr. Fernandez requested given that it is the largest voter in the IMF – tried to win concessions in return for its cooperation. It demanded that Argentina support the Americans’ hard line against Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro and work to limit Chinese influence in the region, specifically by rejecting a 5G proposal by Chinese companies. These were not requests that the Fernandez government found attractive, and he managed to avoid conceding them.

Political fractures

Argentina has a long tradition of fragmented political parties. For example, the Peronist Party, which is Mr. Fernandez’s party and which consistently wins more votes than any other party, has not governed in a unified manner for nearly 50 years.

The current coalition began when former President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who firmly holds the electoral support of about 25 percent of the vote but is hated by another 25 percent or more of the electorate, selected Alberto Fernandez to be the next president while she would serve as vice president. (Mr. Fernandez had been chief of cabinet during Ms. Kirchner’s presidency.) He is more moderate and pluralist than her, and is considered more pragmatic. She, on the other hand, holds tight to her support among the poor and the populist youth groups of her movement within the party.

Ms. Kirchner has since lowered her profile, but she and her followers (who include the governor of the province of Buenos Aires) hold key levers of power within the executive and legislature. For each decision, President Fernandez deals with two challenges: not only does he need to justify his actions to the political opposition, but must first run it by his own party members to avoid a breakdown in the government.

Fernandez faces the challenges that his rule is not yet consolidated.

Ms. Kirchner’s role for the moment has been focused on the judiciary, where she has succeeded in derailing cases of corruption brought against her and members of her entourage. She even got some convicted felons released from jail. She also is interested in anti-market strategies and works to undermine journalists who would write unflattering things about her.

For example, the vice president is behind the recent efforts to expropriate Vicentin, one of the country’s largest grain exporters. Vicentin was in financial difficulty and had begun bankruptcy procedures. A judge blocked the government’s efforts to take over the firm, but in the following weeks, the government backed down. All of this was in keeping with Ms. Kirchner’s belief that state interventions can be used as an economic tool to help the government get through a crisis.

However, President Fernandez appears to be in control of other sectors of the government. During the pandemic, the congress met rarely, and only virtually. He has proven willing to seek points of consensus with the opposition on how to deal with the pandemic and to win their support for what might be called a “Keynesian plan” to spend his way out of the current crisis.

At the beginning of his mandate, Mr. Fernandez enjoyed extremely high approval ratings (84 percent in April). They have since fallen a bit as the public has disapproved of the efforts to expropriate private firms and of the release from jail of members of Ms. Kirchner’s entourage who had been convicted of corruption. In this situation, Fernandez faces the challenges that his rule not yet consolidated, which robs his policy initiatives, few as they are, of their effectiveness. This unstable equilibrium will confront Argentina in the months ahead.

Scenarios

There are two scenarios likely in Argentina and which of them will unfold will depend on whether President Fernandez can consolidate his leadership within the government and deal with the challenges.

Now that Argentina has renegotiated its debt, we can expect that the Argentine economy will rebound from its period of weakness and that the economic or productive capacity of the country will return to normal levels – although it may take a year or more. President Fernandez, with a reputation for pragmatism and an avuncular personality, will likely succeed in keeping Ms. Kirchner operating in pockets or segments of the government that do not upset either national governance or the economy. She might concentrate her activities in the province of Buenos Aires where her protege, Axel Kicillof, is governor.

The less likely scenario is that, in facing these challenges, Mr. Fernandez will not be able to hold his government together to accept the painful terms of the debt renegotiation, caving into the populist left, led by his vice president, which would like to cancel the debt. That will make paying for the economic recovery after the pandemic more difficult and almost certainly drive up inflation. At the same time, Ms. Kirchner will exert her power within the government, with her allies in the province of Buenos Aires and in the national legislature, making it difficult for the president to govern. This will lead to a period of populist policies that endanger Argentina’s position in the global community.