Argentina: Again on the brink of default

Under President Macri, Argentina has fallen into the economic crisis once again. Last month, Argentines elected a new president, Alberto Fernandez, with former President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner as his running mate. To end the downward spiral, Fernandez will have to deftly navigate a political scene and economic challenges.

In a nutshell

- Mauricio Macri was unable to stop Argentina’s slide into crisis

- Argentines have again elected Peronists into power

- A moderate path could work to alleviate the country’s problems

- The radical Peronists could make the situation much worse

Argentina has pitched itself into crisis for the second time this century, and again faces a default on its national debt. This time the country owes only slightly less than it did prior to its default in 2001, the largest in Latin American history.

The debt includes $57 billion from the International Monetary Fund, the largest bailout package the organization has ever provided. The Argentine peso has lost more than 50 percent of its value since the crisis began a year ago. The flight of capital is complicating the central bank’s efforts to maintain its hard currency reserves and is virtually dollarizing the economy (see factbox).

Facts & figures

Dollarization

- Dollarization occurs when the U.S. dollar is used in addition to or instead of the domestic currency of another country. Dollarization usually happens when a country’s own currency loses its usefulness as a medium of exchange, due to hyperinflation or instability.

Source: Investopedia

At the end of October, Argentines voted President Mauricio Macri out of power. Peronist candidate Alberto Fernandez won the election, running with former President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (no relation), as his vice-presidential candidate. Ms. Kirchner is under investigation in 11 corruption cases involving the alleged theft of hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars during her presidency, as well as that of her late husband, Nestor Kirchner.

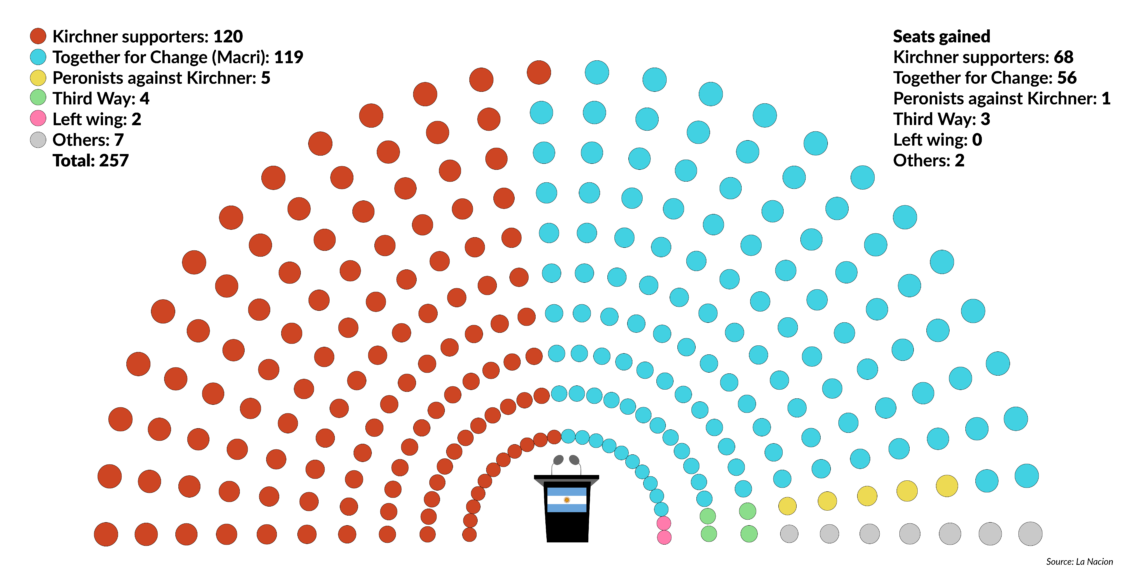

Mr. Macri’s coalition, called Together for Change (Juntos por el Cambio), retained political control of the federal capital, Buenos Aires, and several important provinces. However, it lost Buenos Aires Province (separate from the city of Buenos Aires) and many of the municipalities in the capital’s metropolitan area. The Peronist allies of Mr. Fernandez and Ms. Kirchner won a majority in the Senate, though they fell a few seats short of a majority in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the National Congress.

Economic crisis

Several factors have combined to make for a dire economic picture in Argentina. Inflation is now higher than 50 percent on an annual basis. The government has made big cuts in public spending, part of its deal with the IMF to obtain the bailout. Prices for public services have risen sharply. All of this has led to an increase in the rate of poverty from around 25 percent, the level it had held for more than a decade, to 35 percent in October 2019, with a corresponding rise in extreme poverty. The unemployment rate exceeds 10 percent, the highest level in 12 years, and underemployment is soaring.

Facts & figures

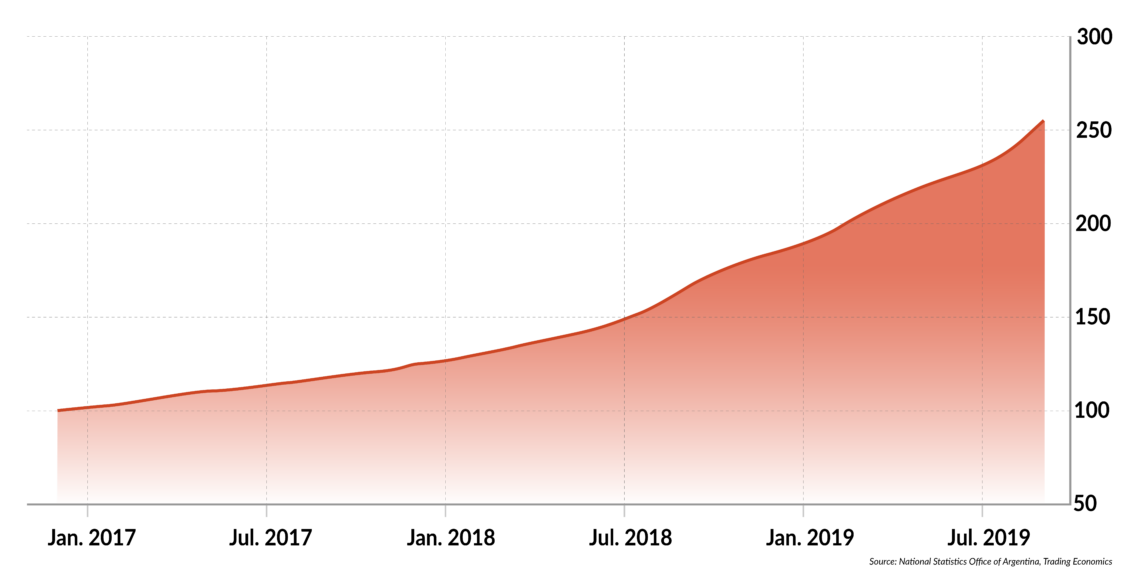

Argentina, Consumer Price Index

(index points, 2017-2019)

In what seemed like the ultimate gesture of defeat, the Macri government reimposed foreign-exchange controls. At the beginning of his term, President Macri lifted the restrictions that Ms. Kirchner had implemented and declared that he would never reimpose them. Consumer spending has fallen, in real terms, each month for the past 14 months. In September 2019, the decline was more than 7 percent from the previous month. Inflation has eroded the middle class’s purchasing power and the crisis has made consumers spend more cautiously.

Analysts predict that the Argentine economy will contract by at least 2 percent in 2019 and probably between 1 and 2 percent in 2020. Economic activity fell 3.8 percent in August, the last month for which official data are available. Manufacturing activity fell by more than 6 percent in October on an annual basis.

Macri’s fall

Confidence in the Macri government began to wane in the first quarter of 2018. The country’s slow economic growth and the lack of investment convinced holders of Argentine debt (many of whom had bought it in anticipation of the reforms that Macri promised) to hedge their bets. That led to a run on the peso – the Argentine exchange market is very thin and easily destabilized. The Macri government was spooked and asked the IMF for a bailout. As we predicted in an earlier report, President Macri’s political fate would be determined by how fast the economy rebounded.

As the economic crisis grew through 2018 and into the early months of 2019, President Macri counted on the support of those who wanted to prevent Ms. Kirchner from returning to power. There was enough hostility toward her among the Peronists that Mr. Macri was confident he could defeat her no matter how badly the economy deteriorated.

In the 2019 general primaries, the Peronists trounced President Macri and his coalition.

Former President Kirchner announced in May that she would run as vice president and back her former ally, Alberto Fernandez, for president. In the August 2019 general primaries, the Peronists trounced President Macri and his coalition. It had become clear that Mr. Macri no longer had any chance of winning the presidential election.

Now the question is how the incoming government will deal with the crisis when it takes power in December. How will it approach the challenges of crushing debt and fiscal insolvency, while coming to the aid of the huge number of newly poor and indigent? How will it stimulate economic activity?

Closed and rigid

Before we analyze the new government’s policy agenda, it is worth examining some of the underlying problems that make sustained development in Argentina so difficult.

Though Argentina is a producer of primary products for export, those exports do not make up a significant share of its gross domestic product (GDP). In fact, it is a rather closed economy, with significant informal dollarization and very little liquidity. Exports make up only 14.4 percent of its GDP, according to the World Bank, in comparison to the Latin American average of 21 percent or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of 28.5 percent.

Argentina’s economy is, therefore, not well integrated into the world economy, making for a low level of competitiveness. The country was ranked 83 out of 141 countries in the recent World Economic Forum Competitiveness Index. Many of its small and medium-sized businesses, which provide the majority of employment, require a high level of protection to remain viable. Meanwhile, Argentina’s export economy is hindered by its increasing dependence on imported components.

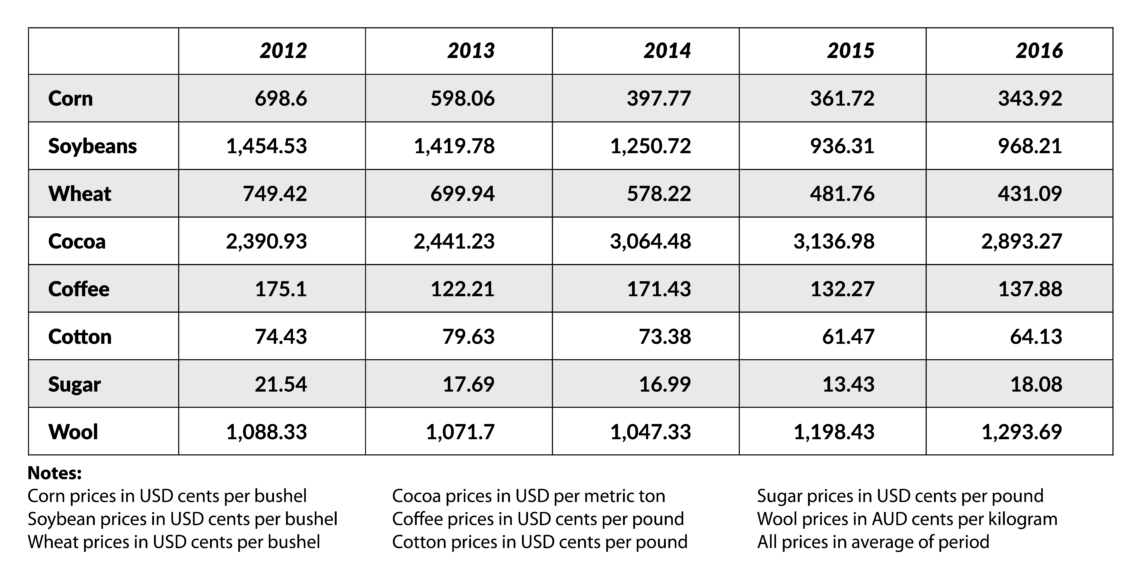

Facts & figures

Historical price data, agricultural products

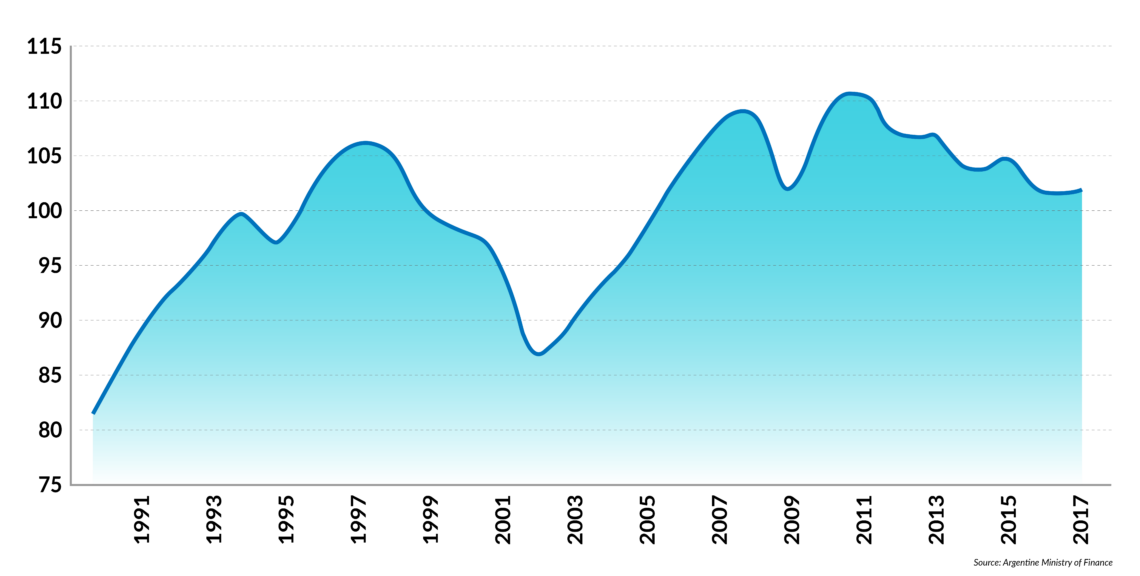

One of the Argentine economy’s biggest defects is its lack of productivity, as measured by total factor productivity (TFP). Argentina’s TFP has fallen over the past few years, even under the business-friendly Macri government, putting the country even further behind the United States and Asia. Without productivity increases, Argentina will find it virtually impossible to sustain GDP growth, even if the prices of its main exports returned to the high levels of the first decade of this century – and there is no indication that will happen, at least not soon.

Facts & figures

Argentina, Total Factor Productivity (TFP), 1990-2017

(1990-2017 average=100)

Rigidity in Argentina’s market structure makes changing this situation difficult, no matter what the government does. Small oligopolies dominate their sectors, inhibit competition and severely limit innovation. Making this last problem worse, Argentina invests less in research and development that any other OECD country.

The country’s tax structure also inhibits investment and innovation. While the tax burden is heavy compared to other developing countries and the state is accustomed to high levels of spending, the lion’s share of that spending is in the form of subsidies and welfare payments – spending that is political in its purpose, not economic. There is comparatively little spending on basic infrastructure, so that the costs of transportation, storage and other transaction costs are high in a region where they are already higher, on average, than in more developed European and Asian countries.

Finally, Argentina’s labor market is highly inflexible. The federal government is engaged in labor negotiations with well-organized unions. These organizations tend to put up hurdles for innovation, new technologies and new methods for organizing work.

Challenges for Fernandez

The new government has two major issues on its plate. The first is the economy, for all the reasons mentioned above. President-elect Fernandez will have to strike a deal with the IMF to, at the very least, extend Argentina’s debt-payment schedule. Meanwhile, it will have to convince the private-sector holders of the country’s debt to extend repayment schedules or, more likely, to insist that they take a haircut. The haircut might be painful, but it will be only a trim compared to what would happen if the country defaults.

Even more difficult, Mr. Fernandez will have to find a compromise between shoring up the pensions that are being eaten away by inflation and a stimulus package to increase economic activity. Any recovery program, however, will lean heavily on protecting state-owned companies and on subsidies, thereby exacerbating inefficiencies.

Mr. Fernandez is known for his pragmatism and his lack of ideological drive.

President-elect Fernandez’s second big challenge will be deciding who wields power in the new administration – the president or the vice president. Ms. Kirchner speaks for the radical, ideological wing of the Peronist movement. Through her favorite economist, Axel Kicillof, who was just elected governor of Buenos Aires Province, and her son, Maximo Kirchner, who will lead at least part of the Peronist block in congress, she can count on a strong base of support.

However, the new president is known for his pragmatism and his lack of ideological drive. He is said to be a master dealmaker, a career politician who prides himself on his skills at bargaining and bringing people together. Argentina’s federal system works to his advantage: the majority of provincial governors do not support Ms. Kirchner. While the national executive wields influence over the governors through negotiations on tax-revenue sharing, it cannot bulldoze them by executive action.

The wing of the Peronist movement that gains greater influence in government will take the lead in setting foreign policy, not a subject close to Mr. Fernandez’s heart. That faction will also shape the government’s energy policy, especially its position on developing the extensive shale deposits in the Vaca Muerta region, in Neuquen Province in Patagonia, as well as the level of government protection for domestic industry and the promotion of foreign trade.

Although foreign policy is not President-elect Fernandez’s strong suit, he has made several comments critical of Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro and in favor of former President Lula da Silva’s return to power. These statements suggest he is ready to accept a high level of tension in the relationship with Brazil.

Facts & figures

Argentine Chamber of Deputies

Results after the October 27, 2019 election

The Peronists are more likely to use the Chinese as a strategic economic ally. China holds a little less than $20 billion of Argentina’s $284 billion total sovereign debt. Chinese banks and state-controlled companies are ready to finance the development of Vaca Muerta and to embark on the most ambitious infrastructure project now on the drawing board: the transformation of the Parana-La Plata river system into an efficient waterway for the export of soybeans and soy by-products.

President Macri had pulled back from cooperation with the Chinese, in part to please the Trump administration. When Ms. Kirchner held power, she saw cooperation with the Chinese as a means of stimulating growth and buttressing her foreign policy, which sought greater autonomy from the United States and U.S.-dominated international financial markets. President-elect Fernandez is likely to share her view.

The opposition itself is in something approaching disarray. President Macri wants to remain as its titular leader. That will be complicated by the advances of the Radical Party, part of Mr. Macri’s coalition, in several important provinces. It will want a larger role in the months ahead. At the same time, Buenos Aires City Mayor Horacio Rodriguez Larreta wants to play a larger role in the national coalition.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that President-elect Fernandez will find a way for the two major Peronist factions to share power. The resulting cabinet will have mixed loyalties and a chorus of voices on major policy questions. Given the depth of Argentina’s economic crisis, it is likely that Mr. Fernandez will take a moderate line in dealing with the IMF and moving toward fiscal equilibrium. Ironically, this will look a lot like the gradualism that President Macri adopted at the beginning of his administration. The economy will probably begin to grow by the second half of 2020.

President-elect Fernandez’s dealmaking will be more effective in political matters. He will be able to control the Peronists in congress, since most of them are moderates. His bargaining skills will help him work with other factions, and it is therefore reasonable to expect that the legislature will not get bound up in gridlock. In this scenario, the immunity that comes with Ms. Kirchner’s office will protect her from the multiple corruption investigations into her dealings. She will leave the leadership of the Peronists’ radical wing to her son Maximo and to Governor Kicilloff.

It is less likely that Ms. Kirchner will gain the upper hand over Mr. Fernandez and that her faction will control the government by putting loyalists in key positions of power. In this scenario, the radical wing will also strong-arm its Peronist colleagues in the congress and get its way with legislation. Such a scenario would prolong the crisis, lead the country to a full default and bring a period of several years in which the government can meet its commitments only by printing money.