Between two trade agreements, Asia-Pacific seeks balance

The Asia-Pacific region is trying to balance its interests with two trade agreements. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership replaces the defunct TPP agreement. Meanwhile, in Asia, the ASEAN members are negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership with six regional economies.

In a nutshell

- Two regional trade agreements are bringing different kinds of benefits to the Indo-Pacific

- The CPTPP replaces the aborted TPP following the withdrawal of the US, liberalizing trade in a host of areas

- The RCEP is a more modest agreement, but by virtue of China’s involvement, represents 30 percent of the global economy

- Several countries in the region are pursuing both deals, recognizing their distinct opportunities

On December 30, 2018, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) went into effect. Led by Japan and comprising seven economies, with four more left to ratify it, the CPTPP is what remains of the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) after the withdrawal of the United States.

Meanwhile, several of the CPTPP member countries – including Japan, Australia, Singapore and Vietnam – are also part of a second, broader arrangement, the ASEAN-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Beyond the clear economic benefits of these agreements, what their common members and aspirants hope to achieve is a balance of influence in the region.

Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership

The CPTPP has been variously described as “cutting edge,” “state of the art” and a 21st-century agreement.” It eliminates 98 percent of tariffs on goods, addresses behind-the-border constraints on trade, and liberalizes domestic investment regimes. Beyond tariff cuts, the highlights include a prohibition on the forced localization of digital data; treatment of foreign investment as equal to domestic treatment; recourse to arbitration, i.e. investment-state dispute settlement; rules of origin that facilitate intra-regional trade; and a negative list for liberalization of the service industry. The last item means that service sectors are open unless specifically singled out – which is important in fast-evolving areas like information technology and financial services. There are also binding commitments on extraneous issues, like labor and the environment.

The CPTPP represents approximately 13 percent of global GDP, down from what would have been 60 percent in the TPP, which included the U.S. For the nations that are part of it, the CPTPP represents real opportunities for growth. According to modeling by Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Southeast Asian signatories and New Zealand stand to gain 1-2 percent in GDP growth, and Japan and Australia somewhat less.

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

The RCEP is an initiative of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), not China, as is commonly assumed. As such, it takes a classically ASEAN “lowest common denominator” approach to trade negotiations. This is not entirely bad; ASEAN’s low-grade economic integration is the organization’s greatest success. That has also been its approach to bilateral trade agreements with partners from outside Southeast Asia, including China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand.

In now its seventh year and 25th round of negotiation, the RCEP seeks to deepen economic ties among six Asia-Pacific economies and the 10 members of ASEAN, mostly by harmonizing current trade and investment regimes. By all accounts, it will achieve significantly less market liberalization than the CPTPP, whether through the removal of tariff and nontariff barriers or services liberalization and disciplines on state-owned enterprises. It will have no labor or environmental protections.

The RCEP takes a classically ASEAN lowest common denominator approach to trade negotiations.

But by virtue of China’s involvement, the RCEP represents 30 percent of the global economy. Along with the fact that its economies have higher barriers generally than those in the CPTPP, that means its benefits to participating countries are greater. The same RSIS study cited above predicts significantly greater levels of GDP growth for CPTPP signatories also signing on to the RCEP. Those countries in the region which have not yet signed the CPTPP would gain more by simply joining the RCEP.

China’s economic position

Still, the RCEP should be kept in perspective, as it faces a great many substantive disagreements to overcome. Only seven of its 20 chapters have been finalized – and none in the most contentious, significant areas, involving investment, goods and services. At the same time, there are new governments to contend with. Recent elections in India, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia will require negotiators to take political stock and recalibrate positions.

In a best-case scenario, negotiators will come to an agreement by the end of the year but will have to lower the liberalization bar even further to get there, reducing the RCEP’s benefits. In the worst case, they will miss yet another deadline. Six years is not too long to negotiate such a massive agreement that includes the second and third largest economies in the world (China and Japan), and India. Both of the former have agreements with ASEAN, but not with each other.

Yet even without the RCEP, China’s economic position in the region is strengthening. China is the largest export market for 11 of the 15 other countries negotiating the RCEP, and since 2015, it has become the leading export destination for the Philippines and Indonesia. With regard to investment, since 2000, China has gone from nowhere among ASEAN’s international investors to more than 6 percent of the market. In terms of flows of investment, it ranks fourth, behind only intra-ASEAN investment, the European Union and Japan. For some countries – such as Cambodia, Laos and even Malaysia – more investment is now coming from China than anywhere else.

That said, the idea that China’s economic dominance of the region is imminent would be an overstatement. Numbers on trade and investment reported by ASEAN show steady gains by China and persistent diversification. In terms of investment inflows, Japan leads in Indonesia and Thailand, for instance, and South Korea now leads in Myanmar and Vietnam. Other ASEAN countries, the EU and the U.S. remain the largest investors in the region cumulatively, as well as major trading partners.

Facts & figures

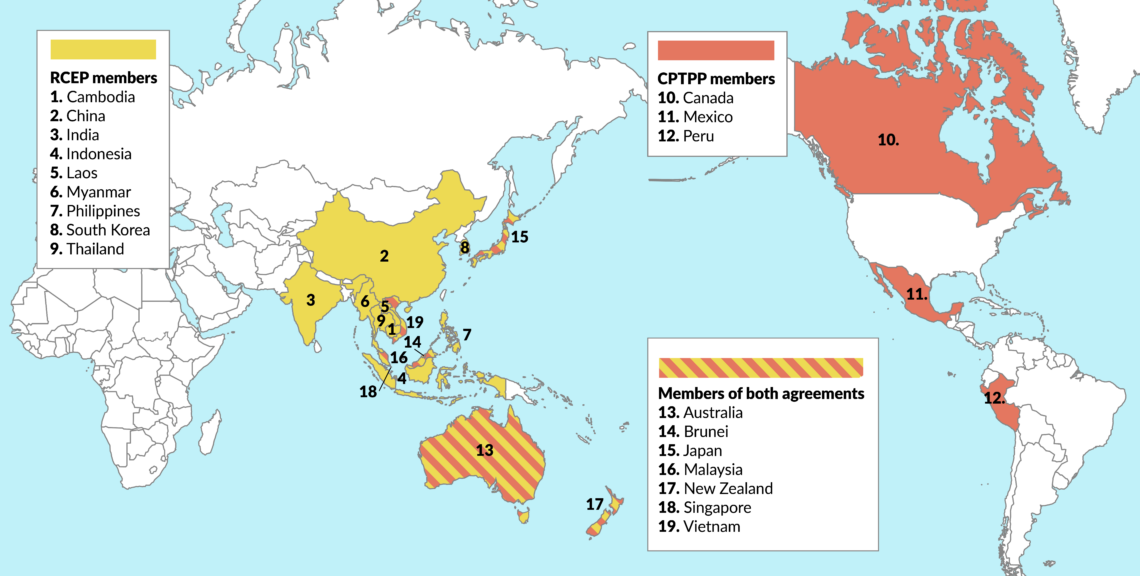

CPTPP and RCEP participant countries

This is not completely by accident or by force of the market. ASEAN’s raison d’etre is the maintenance of autonomy and freedom of maneuver for its members. The members of the CPTPP and RCEP have similar interests. China may now be the leading export market for Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, but the region has an interest in trading partner diversity. This was one of the primary motivations behind the effort to maintain momentum on the TPP after the U.S. withdrawal.

Another motivation was assuming the role of rule-maker. The CPTPP puts its members in the lead agenda-setting position. It is open to new members, and in fact, many countries in the region and beyond have expressed interest in joining, including Thailand, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Colombia and the United Kingdom. This, of course, will increase the value that the deal presents in real terms, but it will also further socialize its rules. The deal is even open to China joining. That may be unlikely, but the more the CPTPP grows in dollar terms, the more its influence grows – whether or not China joins.

The economies in the region also have an interest in completing the RCEP, not only for the economic benefits reflected in the RSIS study but also to constructively engage China. The containment-type logic that has seized much of Washington in recent years finds very little resonance in the Indo-Pacific. To the extent it does, it is mostly in New Delhi, which, not incidentally, has a smaller stake in the Chinese economy than its RCEP partners. India, it should also be noted, is the biggest obstacle to completing the agreement.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario going forward stitches together these elements, plus two more. China will continue to gain market share and the region will continue to engage it constructively, seeking Chinese trade and investment. Concerns will continue to be raised about trade deficits and about initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

These concerns will inform RCEP negotiations, which will be completed this year or next. They will also force changes in specific business deals and in the BRI’s governance. The region will deal with remaining concerns by continuing to seek diversity in its economic ties and by socializing CPTPP rules. By the same token, countries in the region will continue outreach to the EU and the U.S. The EU at this point has key trade agreements under its belt with Japan, South Korea, and several others pending or under active consideration. Engaging the EU is essentially pushing on an open door.

The U.S. is a different story. At worst, in a phenomenon bigger than the Trump administration, Washington is retreating into an autarkic fantasy world. At best, it wants to drive exceedingly hard bargains. Negotiations with a partner that demand one-sided outcomes are difficult for the region to swallow. The public and contentious way that America’s negotiations have unfolded with China, Canada, South Korea, and Mexico only compound the region’s reluctance.

A U.S.-China agreement is likely, but tensions over trade, especially over the enforcement of any agreement, will persist over the long term. Meanwhile, two things will make an agreement with Japan possible. For the U.S., pressure is increasing from farmers already suffering from the loss of market share in China and competition from exporters benefiting from the CPTPP. On Japan’s part, it wants to stave off new unilateral American tariffs on autos and otherwise keep U.S.-Japan relations on an even keel. Still, there are quite a few hurdles to overcome, over both Japanese negotiators and constitutional procedures in Washington.

The CPTPP and the RCEP are often held up as competing initiatives that will determine the geopolitical shape of the Indo-Pacific. This is not quite the case; countries in the region have an interest in pursuing both. While recognizing that trade agreements only represent part of the economic activity in the region, it is this broader quest for balance that will have a determinative impact.