The implications of a shrinking Asia

China, Japan and South Korea are in demographic decline. Is that good or bad?

In a nutshell

- Government financial incentives may be useless in reversing the demographic slide

- Aging societies bring greater economic costs but could also help the environment

- The fastest way to reverse population declines is a relaxation of immigration policies

Briefly after the Cold War, when globalization dominated the world, national sovereignty seemed relegated to the dustbin of history. The Western consensus of liberal democracy, market economy and free trade had triumphed for good, or so we thought.

The main concerns of this age? The management principles of just-in-time delivery and global sourcing. A World War I-style bloody trench warfare? Never again in Europe.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 altered the situation dramatically. Suddenly, humanity is no longer at the end of history, but right in the middle of it. Long-held beliefs had to be substantially revised. The priorities of trade and economic growth had to be replaced with the imperative to build strong armed forces.

National security once again depends on the number of tanks and artillery pieces. Today’s supply-chain questions include how many soldiers a country can mobilize and how quickly it can do so. The strength of a nation is once again measured by the dark ages criteria of the 19th and 20th centuries.

But military might is not the only yardstick. Demographics – the size, birth rate and age structure of a given population – is intricately linked to the strength of a nation as well, along with social and economic conditions that encourage or discourage people from having families.

Population and resources

In Asia, for a long time after World War II, the Malthusian fear reigned supreme: Rapid population growth would cause massive famines and a shortages of resources. Population growth would stall socioeconomic development. The worry was so great that the two largest countries by population, China and India, adopted policies to control population growth.

In India, this rigid intervention only survived for a short time during the 1970s when a program of enforced sterilization was implemented. In China, the one-child policy was launched in 1980 and only revoked some 36 years later. Relentless population growth was seen as a major threat to the peace and stability of civilization. The world seemed destined for doom as the global population in November 2022 crossed the 8 billion mark.

Also by Urs Schöttli

Japan needs woman power

Fewer births and aging populations

But today, the fears are different. Important countries in Asia and other parts of the world are faced with the new challenge of a shrinking and aging population. China has abolished its one-child policy and authorities are now campaigning for young people to get married and have many children. At first people were allowed two children. Now the authorities promote the idea that the more children the better.

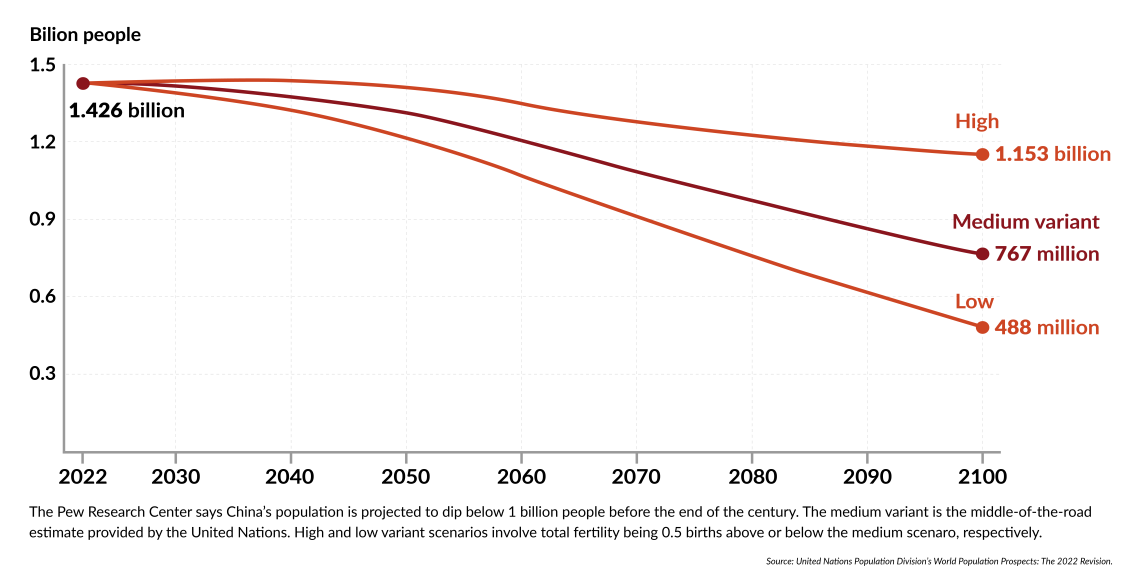

The reasons are clear: 12 percent of China’s population, some 166 million people, are 65 or older. The growth rate has dropped to 0.49 percent and the fertility rate is down to 1.7 children per woman, putting the People’s Republic 148 out of 190 nations. China is far from the rate of 2.1 children required to maintain a stable population. Without change, according to the French Institute for Demographic Studies, the Chinese population will fall to 1.3 billion by 2050, with an accelerated drop to less than 800 million in 2100.

The situation is even worse in neighboring Japan and South Korea. Japan’s population is declining by 0.17 percent per year, while South Korea’s is growing at a meager 0.36 percent. The fertility rates are 1.1 children in South Korea and 1.4 in Japan. The prospects in both cases are alarming, with Japan’s population, which today stands at almost 126 million, dropping to 104 million in 2050 and a mere 72 million in 2100. The figures in South Korea’s case, now with 52 million people, are 46 million by 2050 and 24 million in 2100. In both cases, there is little scope for even drastic action by the government through monetary incentives and social pressure to reverse this trend.

India and Indonesia present a different picture. India will soon, if it has not already, overtake China as the world’s most populous country – both now with more than 1.4 billion people, but on different trajectories.

Currently India’s annual growth rate is 1.2 percent, with a fertility rate of 2.1 children. By 2050, India’s population will rise to 1.7 billion and thereafter stabilize at 1.5 billion in 2100. India’s population pyramid by age continues to be healthy, with only 6 percent, or 85 million Indians, 65 or older. Indonesia is following a similar track with a fertility rate of 2.2 children and the prospect of a population of 317 million by 2050 and thereafter 297 million by 2100.

The great exception is Pakistan, with a growth rate of 2.37 percent and a fertility rate of 3.3 children, far above the replacement rate. By 2050 Pakistan will have 366 million inhabitants and 490 million by 2100.

Impacts of a demographic decline

Those concerned about the ecological impact of a continuously rising world population will welcome the demographic trend in most parts of Asia. The globe likely could not provide Asia’s 4.5 billion people with living standards like those in the industrialized West. Already today, the rapid growth of the Asian middle class is putting a great strain on resources, leading to air pollution and shortages of drinking water, among other problems.

From this point of view, Asia’s slowing population growth is good news. However, not all is positive. A declining population has several negative effects, of which the most pressing are reduced consumer spending, a less robust workforce and the psychological impact of a smaller and aging population. Consumer patterns from Shanghai to Tokyo, from Guangzhou to Osaka and Seoul, show remarkable changes. With fewer consumers and households, demand for durable consumer goods, housing and cars inevitably decreases.

More immediate will be the negative impact on the labor market. China managed to become the “workshop of the world” because of its competitive and cheap labor force. In many fields, particularly those with highly skilled workers, salary levels have leapt. In major urban and industrial centers, they have even caught up with more advanced economies. China is seeing a substantial reduction in its labor force that will accelerate, and which it may not be able to compensate for through automation and innovation.

Japan is rapidly aging. Together with South Korea, Japan will face a massive social security burden. In China, the prospects of an aging society are even more alarming with its comparatively modest economic development. Japan has a nominal per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of some $38,000, while China’s nominal per capita GDP is $8,600. Economists are, therefore, looking at a Chinese society that is growing old before it has grown rich, the reverse of what has happened in the industrialized West during the past six decades.

While economists focus on the material aspect, there are also mental, psychological and even political issues to consider. The growth in the proportion of elderly people could lead to a more conservative society focused more narrowly on the interests of its generation.

Furthermore, there is the question of how a shrinking society will face the challenges of the 21st century. These trends are more noticeable in Japan than China now. People may become more withdrawn and egotistical. Not marrying or creating families is an expression of how one feels about the existing society. In China, young women are refuting calls to have children. Rapid urbanization can further reduce the incentive to sacrifice. Who wants to be housebound if you can pursue a career and an independent life?

The stage at which demographic changes happen varies greatly. There are also traditions, some of them religious, that interfere. While China is shrinking, the Philippines is still growing. This has to do with the strong position of the Catholic Church in this former Spanish colony. While in China family planning has a long tradition, the Philippines remains strongly influenced by Catholic values. Religion also plays a part in the strong population growth in Pakistan, where Muslim clergy members are influential.

New strategies for population policies

Changing demographic trends is a very complex and delicate undertaking. Demography has a lot to do with the national economy and structure of society. It is also deeply personal. A state can provide monetary incentives, career chances and appeal to social responsibility. But, in the end, the future is defined by the most personal decisions that human beings make during their lifetimes. There is nothing more personal than getting married and having children. Authorities can encourage or coerce, such as the enforced sterilization in India during Indira Gandhi’s rule. The ability to have a safe and legal abortion can also have a substantial impact.

In nations with fewer people, the government focus is on providing financial incentives for couples to have children. We can see this in Japan, South Korea and China. Women also want to pursue careers along with family, but conditions for combining the two are still not ideal.

In China, the one-child policy also created a severe gender imbalance, with girls aborted or neglected because of the traditional preference for male offspring. Sometimes lone children become spoiled and never learn to share. In adulthood, this can lead to egotistical or antisocial behavior. As Covid-19 showed, a totalitarian regime can use a lot of intimidation and oppression. However, these crude instruments generally do not work in family policies. Beijing needs a strategy that combines incentives and soft power with values and ideals if it wants to reverse its population decline.

Finally, immigration is also important. Both Japan and South Korea have a very homogenous population and have been reluctant to open borders for large-scale immigration. However, labor shortages in such vital areas as healthcare and services have become very pressing. Soon enough the authorities will have to decide whether they are willing to change their policies and open the doors to more immigrants.

Scenarios

Shrinking populations are most acute in Japan and South Korea, but China is catching up. In Tokyo and Seoul, political leaders are aware of the challenge but have yet to change the mentalities at the root of demographic decline. Now the emphasis is on enhancing conditions to encourage young couples to start a family. All these financial incentives will fall flat, however, if lifestyles take hold in which people prefer to have no children or are not optimistic about the future. Social problems inherent in an aging society, major ecological threats and difficulties to find stable employment all dent optimism for a brighter tomorrow.

The fastest remedy is a relaxation of immigration policies. But it is still not likely to happen, given attitudes in Japan and South Korea. In 2022, the share of foreigners in the Japanese population was 2.2 percent; in South Korea 3.4 percent. Last year Japan set a record in the still small number of foreign workers allowed into the country. Cultural hurdles, particularly in terms of language and societal integration, are substantial when compared with other Asian countries. Both South Korea and Japan have no tradition of large-scale immigration. Both are considered rather insular, even within their own region. While Japan is an island nation perceiving itself as unique, South Korea is cut off by the world’s most dangerous and closed land border.

China’s problems are less pressing, but it will continue to suffer from the effects of its one-child policy and the difficulty of changing gears. As demonstrated by the Covid-19 pandemic, there is considerable restlessness when it comes to governmental interference into private matters. The best scenario for Chinese authorities is to provide social and monetary support. Coercion is not going to work.