AUKUS and the Sino-Western rivalry

Though Beijing claims that the new AUKUS alliance is the start of a new Cold War-style arms race, its formation was a response to surprising military technology developments in China. It is also a symptom of a new, volatile era of asymmetric rivalry in the region.

In a nutshell

- AUKUS is a response to Chinese military expansion

- Beijing claims the alliance could start an arms race

- The West-China rivalry is entering a new, dangerous phase

The announcement of AUKUS, a new Indo-Pacific security alliance between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, has already had a profound impact across the region. For Taiwan, it immediately offered strategic reassurance. In Southeast Asia, the news unsettled some countries. For China, AUKUS may undermine the advantages Beijing thought it had gained from newfound nuclear capabilities.

Through the creation of a trilateral security partnership, the AUKUS countries have declared their resolve to deepen diplomatic, security and defense cooperation in the region to meet the “challenges of the 21st century.” The British government’s AUKUS launch statement identified the Indo-Pacific as being at the center of intensifying geopolitical competition and potential flash points, including territorial disputes, cyberspace threats and importantly, nuclear proliferation.

The alliance clearly intends to counterbalance China’s burgeoning military expansion, assertive diplomacy and coercive behavior in Asia. Its genesis can likely be traced back to a G7 summit hosted by the UK in June where a joint statement by all three AUKUS members echoed the language used at its launch.

Converging interests

The convergence of strategic interests then provided the ingredients for AUKUS. It has delivered on U.S. President Joe Biden’s pledges to build partnerships and coalitions in the region. It will also provide substance for UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s “tilt” toward the Indo-Pacific and potential military exports to the region, underpinning his “global Britain” mantra. Australia, for its part, will obtain advanced submarine technology from the U.S. and the UK. And if AUKUS lives up to the lofty goals proclaimed by its founding members, it will curb China’s regional hegemonic ambitions.

The Indo-Pacific will become the test bed for the world’s most advanced military technologies.

According to the agreement, trilateral cooperation will also encompass joint activity and interoperability in areas such as cyber technologies, artificial intelligence, quantum computing and additional “undersea capabilities.” This alludes to the creation of sophisticated “C4ISR” networks across Asia. The acronym stands for command, control, communications, computers (C4), along with intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR).

The combined geographic reach of the U.S., Australian and British military forces will offer powerful early warning and deterrence capabilities in countering China’s advances. In the next decade, the Indo-Pacific will become the test bed for the world’s most advanced military technologies – including China’s. Beijing’s launch into space of the world’s first hypersonic glide missile this summer represented a turning point in the military rivalry between China and the West and may have been the key catalyst for the formation of AUKUS.

China pushes back

China’s counter-AUKUS narrative focuses on the nuclear proliferation concern, portraying the alliance as an Anglo-Saxon cabal that is imposing an arms race on the region. That argument is gaining some traction.

Chinese diplomats are also deliberately conflating nuclear propulsion with nuclear armament. At a recent China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi asserted that AUKUS would endanger the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty, damaging regional peace and stability. Mr. Wang also promised to work with Pacific Island countries to safeguard the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty. Commentators from the strategic community in China insist that Australia joining AUKUS is tantamount to it becoming a nuclear-armed country.

Facts & figures

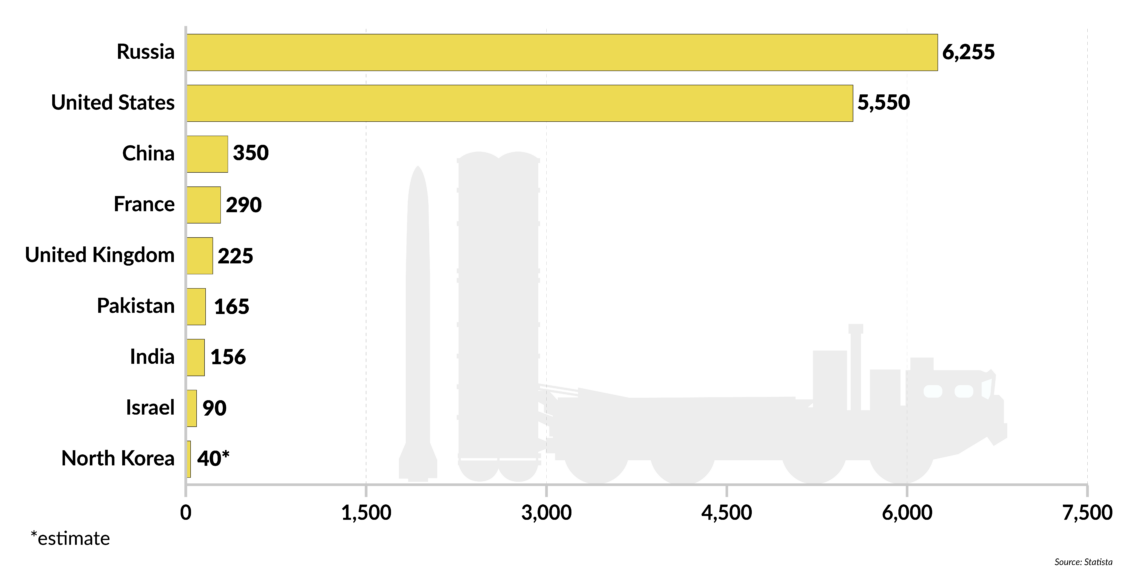

Nuclear powers

Number of nuclear warheads as of January 2021

Hong Xiaoyong, China’s ambassador to Singapore, has said that the U.S. and the UK could export weapons-grade nuclear fuel to nonnuclear Australia, bypassing International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards. Ambassador Hong described AUKUS as a “Pandora’s box” that would lead to deeper mistrust and an arms race. Chinese Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Le Yucheng said countries in the region should “oppose and resist” AUKUS, which he called a “small bloc composed of Anglo-Saxon nations” that “advocates a new Cold War.”

There is evidence that China’s argument is finding a receptive audience in Southeast Asia. On September 22, Malaysian Defense Minister Hishammuddin Hussein announced that his country planned to seek China’s view on AUKUS, only days after Indonesia and Malaysia warned that the security pact might trigger a nuclear arms race in the region.

Hypersonic weapon

Beijing’s complaints ignore its own nuclear activities that promote proliferation and upset the strategic nuclear status quo in the region. According to recent revelations by the Financial Times, China has successfully tested two hypersonic glide vehicles launched aboard Chinese rockets. Such vehicles are designed to travel at a speed of Mach 5 toward their targets, are highly maneuverable and are longer range than conventional nuclear ballistic missiles because they partially orbit the earth.

The U.S. intelligence and weapons development community appears to have been caught off guard. It is still unknown whether this weapons platform is operational – the parading of the DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle mated with a DF-17 missile system in October 2019 during a national day parade in Tiananmen Square might suggest so. Even though the FT reported that one of the recent tests failed to reach its target, the launches have opened a new chapter in nuclear deterrence.

China has been working hard on developing a nuclear triad, able to launch weapons from land, sea and air.

There is also evidence elsewhere that China is increasing its nuclear capability both quantitatively and qualitatively. A report in September by the Arms Control Association revealed evidence that China is building up to 250 new long-range nuclear ballistic missile silos in several locations in the northwest of the country.

China has been working hard on developing a nuclear triad. In addition to the abovementioned land-based assets, it will incorporate submarine-launched and air-launched nuclear weapons. China may have created its military outposts in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea to protect its new sea-based nuclear deterrent, while its new range of strategic bombers is designed to offer China “assured retaliation,” if the U.S. were to mount a nuclear attack.

In recent years, China has become far more sensitive to any military deployment that might hinder its assured retaliation and second-strike capability. A case in point was Beijing’s response to the U.S.’s deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system in South Korea. THAAD is designed to intercept ballistic missiles in their final phase and was deployed to counter North Korea’s missile threat. China, however, complained that the system could undermine its own nuclear deterrent. As a result, Beijing imposed unofficial economic sanctions on South Korea, causing considerable harm to the country’s businesses.

Since China has become a nuclear power, its leaders have maintained a stance based on restraint. Beijing assiduously stuck to a “no first use” defensive policy – it would only use its nuclear warheads in retaliation. For decades, China’s nuclear arsenal was roughly the same size as those of the UK and France, and nothing close to the enormous arsenals of the U.S. and Russia. Recently, however, U.S. leaders and prominent figures in the deterrence community have argued that China is seeking to significantly increase its arsenal.

Moreover, the development of the new hypersonic glide missile shows that China is working on new ways to defeat U.S. defense systems. It could add a fourth capability to China’s nuclear triad – one that is space-based. In this context, AUKUS takes on even more far-reaching significance for nuclear deterrence.

AUKUS impact

The initial debate about AUKUS has focused on Australia’s procurement of nuclear-powered submarines and the balance of military power in the West Pacific. Less has been said about the alliance’s other goals, especially in developing and integrating advanced technologies. Interestingly, New Zealand’s ambassador to Australia suggested that Wellington could collaborate with AUKUS on quantum computing and artificial intelligence. This is an early sign that AUKUS may be open to new members or third-party partnerships, and could collaborate with other friendly alignments, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, which includes Japan, India, Australia and the U.S.

A hypersonic glide vehicle could wreak havoc on U.S. bases and carrier strike groups.

Both China and the U.S. know that for the next decade or so, the ability to win a conflict in the region will rest on conventional capabilities – those below the nuclear threshold. Still, a hypersonic glide vehicle armed with conventional warheads could wreak havoc on U.S. bases across the Indo-Pacific and American carrier strike groups, hindering a military response to an invasion of Taiwan, for example.

Without fear of U.S. nuclear coercion, China could use conventional firepower to overwhelm its enemy. AUKUS is therefore likely to focus on defeating China’s asymmetric capabilities and any other platforms that threaten the status quo in the Western Pacific. China has been developing such systems for more than two decades. The DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle is one such example and more are sure to come.

New era

The creation of the AUKUS alliance is a symptom of a new, volatile era of asymmetric rivalry in the Indo-Pacific. Dr. Luo Xi, a research fellow at the China Arms Control and Disarmament Association, has said the world is entering a new era of “post-ballistic” missile technologies. The AUKUS-China rivalry will likely move into the domains of directed energy weapons, direct ascent anti-satellite weaponry, space-based weapons and large-scale cyberattacks. AUKUS will likely focus on China’s new and secretive Strategic Support Force, a branch of the PLA that fuses cyber and electronic warfare with China’s space assets.

This new phase of rivalry will also fuel a nascent debate about the proliferation of artificial intelligence-enabled weaponry. The PLA may already be considering ways to remove the human element from tactical calculations in a fast-moving and digitally enabled battlespace, a factor that AUKUS planners will be tackling.

Moscow is not only able to disrupt the status quo in Europe, but also in the Indo-Pacific.

Finally, AUKUS will be confronting the PLA’s psychological and political warfare capabilities, particularly regarding Taiwan. Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi recently drew upon Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War”to describe a war over Taiwan won without any fighting taking place. Drawing comparison to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Mr. Kishi warned that an invasion might start without anyone realizing it.

Of course, Moscow is not only able to disrupt the status quo in Europe, but also in the Indo-Pacific through military collaboration with China. The Kremlin has traditionally not taken a position on China’s territorial disputes but does see eye to eye with Beijing on countering the AUKUS aspiration for a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” a policy term which both Russia and China view as an attempt to impose a Western-dominated rules-based order.

In recent weeks, China and Russia deployed a joint group of several powerful warships which skirted around Japan and transited the Tsugaru Strait between Honshu and Hokkaido, a considerably provocative move. It is highly likely that as AUKUS grows teeth in the Indo-Pacific, China and Russia will push back increasingly hard through multi-domain joint operations.