The Balkans dangle on the periphery of Europe

With France on a mission to reform the EU before allowing membership for Balkan states, the region remains both divided and politically isolated. The longer the EU keeps the Balkans from integrating, the greater the chances they fall under Russian influence.

In a nutshell

- A French initiative would make joining the EU much harder

- Some want to make the Balkans a refugee host area

- Meanwhile, Russian influence in the region is growing

The Western Balkans’ geopolitical future is becoming more unpredictable by the day. European Union enlargement is indefinitely on hold, and if it is not shut down completely, then it will likely at least be held off for several years. This is mostly because France, under the leadership of President Emmanuel Macron, opposes the process.

In October, Paris led a group of EU countries that blocked Albania and North Macedonia from starting membership talks as scheduled. Now, the Macron government is proposing a new methodology for EU accession that could make joining the bloc much more difficult. During its EU presidency starting in January 2021, France is set to prioritize reform of the bloc over enlargement.

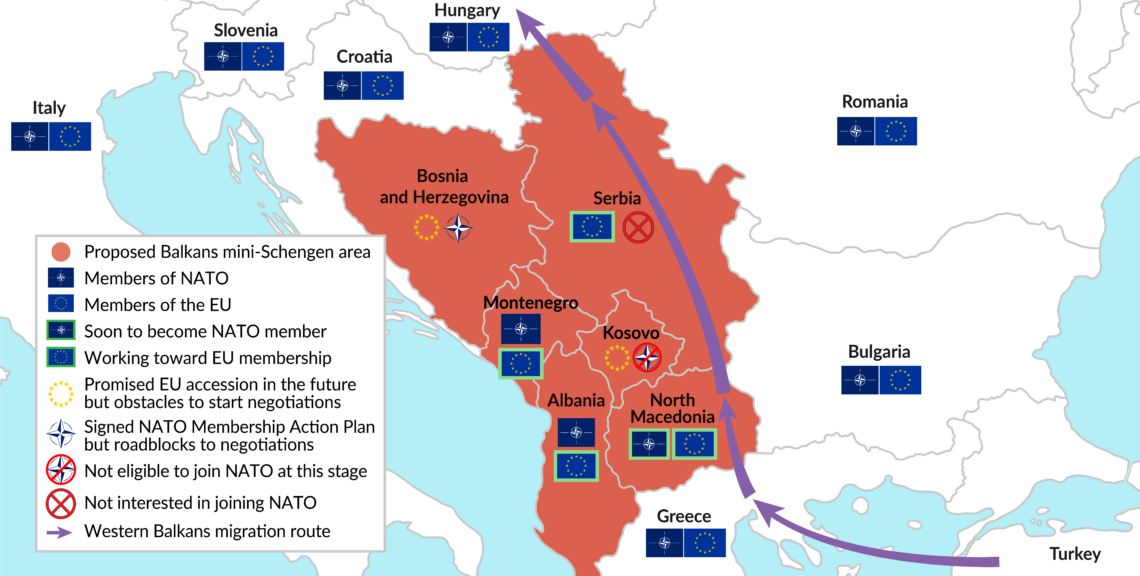

President Macron has questioned another key Euroatlantic geopolitical structure, NATO, calling it “brain dead” in an interview with the Economist in November 2019. Joining NATO is considered a crucial element in the Balkans’ integration with the rest of Europe. Albania and Montenegro are already members, while North Macedonia is due to join early this year.

A Pentagon report expressed worry about Russia’s growing influence in the Balkans, particularly in Serbia.

Germany, for its part, has indicated that when its EU presidency begins in July 2020, it will push for the Western Balkans to become a host area for African and Middle Eastern refugees, which would also complicate the countries’ EU membership prospects.

On the other hand, a recently revealed Pentagon report expressed worry about Russia’s growing influence in the Balkans, particularly in Serbia. Taking all this into account, it is clear that the next two years will be decisive not only for the region, but for all of Europe.

Battling non-papers

In November 2019, France began circulating a “non-paper” drafting a proposed agreement among EU members on a new methodology for the accession process. The proposal was put on the back burner, due to resistance from several other member states. In fact, Austria responded with its own non-paper, supported by eight other member states, which voiced opposition to the French proposal and disagreed with the position that EU reform must be a condition for further enlargement.

France’s hope is to push its proposals through by the March 2020 EU Council meeting and before the Western Balkans summit in Zagreb, scheduled for May. The Austria-led bloc worries that if France’s new accession methodology is approved, the window for negotiations with Balkan states will close irrevocably.

The French paper did not mention “enlargement,” instead using terminology like “gradual association” and “accession process.” The former term was listed as one of four principles of the new methodology, along with stringent conditions, tangible benefits and reversibility.

Facts & figures

Currently, EU accession is based on the opening and closing of 35 “chapters” of requirements that candidate countries must meet. The French document introduced seven phases, each with its own chapters. Crucially, these chapters would never fully close – they would be subject to reopening at any time. The entire process is made reversible, with no guarantee for a country that once it finishes a chapter that it will not have to go back to it again. If accepted, this new methodology would certainly further delay EU enlargement, likely keeping all of the Western Balkans from becoming members for at least another two decades.

The European Commission is likely to take elements from both non-papers and combine them in a compromise strategic document sometime in the first half of this year. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has already repeated her country’s well-known position that it supports Albania and North Macedonia being allowed to begin the accession process. President Macron, for his part, has reiterated that he will not lift his country’s veto against the two countries entering the EU until the bloc undergoes reform.

The prospects for the Balkans’ EU accession therefore depends to a large degree on the final result of the haggling among member states over the various documents and visions. There are reports that Germany has a document of its own, this one on immigration policy, by which it proposes making the Balkans a buffer zone where African and Middle Eastern migrants could remain instead of entering the EU. That proposal is expected to be formally submitted after July 1, 2020, when Germany takes over the rotating EU presidency.

The new European Commission, under President Ursula von der Leyen, is making migration a top priority. The Juncker Commission’s action plan on integrating third-country nationals and the EU initiative which effectively paid Turkey some 6 billion euros to retain 4 million refugees on its soil have not resolved the issue. High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell has expressed the need for agreements both with migrants’ countries of origin as well as transit countries – that is, in many cases, the Balkans.

Countries in the region fear the EU would like to turn it into a giant refugee camp, again raising the problems that occurred during the migrant crisis of 2015-2016, when millions of migrants crossed the region in an effort to reach the EU.

France, for its part, is working on a draft strategy to reform the EU by 2022, an initiative it wants to kick off when it takes over the rotating EU presidency in January 2021. To do so, Paris may call a convention to forge a new EU agreement to replace the Lisbon Treaty. The core of the reform is to be based on President Macron’s philosophy that the bloc must be “deepened before it is widened.” However, Enlargement and Neighborhood Policy Commissioner Oliver Varhelyi has argued that the two are not mutually exclusive. The European Parliament also takes the position that EU reform and enlargement can be carried out in parallel.

Rising Russian influence

While the EU is preoccupied with internal reform, the U.S. is worried about Europe’s external risks. Last year, Radio Free Europe gained access to a Pentagon report that detailed how Serbia’s cooperation with Russia had intensified since 2012, when President Aleksandar Vucic came to power. The report also stated that the Pentagon supported the creation of a Kosovo Army as a strategic step against Russian expansion in the region. During a visit to her country’s troops in Kosovo in December, German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer warned of Russia’s growing influence in the Balkans. Later in the month, the EU extended its sanctions on Russia for its role in the Ukraine crisis for another six months, until mid-2020.

The West’s worries were heightened when Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov confirmed at the beginning of December that Serbia was interested in buying a Pantsir anti-aircraft missile system. There has also been speculation that Belgrade might be interested in purchasing an S-400 system from Russia, the same type that Turkey recently bought.

On December 4, President Vucic met Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi – the leaders’ 17th meeting in seven years. In a press conference thereafter, President Putin said that any resolution to the Serbia-Kosovo issue must “respect the sovereignty and integrity of Serbia.” That position contrasts with Washington’s stance that normalization requires “mutual recognition” between Kosovo and Serbia.

Unresolved conflicts, like the one between Kosovo and Serbia, keep the Western Balkans in a geopolitical limbo.

Of course, Russia’s opposition to Balkan countries joining Western structures is nothing new. As Maxim Samorukov, a fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center, put it, “Russia’s main objective in the Western Balkans remains the same: to stymie the expansion of NATO and the EU.” Unresolved conflicts, like the one between Kosovo and Serbia, but also throughout the region, “keep the Western Balkans in a geopolitical limbo, in which Russia’s meddling is easily amplified,” he added.

On November 12-13, 2019, a Russian-Balkan summit was held in the Russian city of Voronezh to mark the launch of a Moscow-led organization aimed at preventing Balkan states’ integration into NATO and the EU (encouraging them to adopt a so-called “neutral” policy), and pushing them toward regional integration. Russia’s argument is that Balkan countries do not need others to tell them what to do.

Aware that it will not be able to occupy parts of the Balkans as it did in Ukraine (Crimea, Donbas) or Georgia (Abkhazia, South Ossetia), Russia will likely pursue a policy of maintaining the frozen conflicts in the region to prevent the region’s Euroatlantic integration. Therefore, Moscow will not expand its influence in the Balkans through military hard power, but through three other vectors: Slavic “brotherhood,” Orthodox Christian ties and hybrid war, (cyberattacks, fake news and propaganda). A significant number of media outlets in the region are under Moscow’s influence.

All of this is happening just as NATO is celebrating its 70th anniversary – a time when it must deal not only with a newly assertive Russia, but also with Turkey and France following policies that increasingly diverge from the alliance’s. After buying the Russian S-400 system and attacking the U.S.’s Kurdish allies in Syria, at the NATO summit in London in December, Ankara threatened to veto a defense plan for the Baltic states. President Macron, for his part, after declaring NATO brain dead and calling for setting up a European security architecture independent of the alliance, has now said that NATO should engage in a “strategic dialogue” with Moscow, and that Russia is not an enemy of NATO.

‘Mini-Schengen’ proposal

Meanwhile, in the Balkans, regional players were jockeying for leverage. In October 2019, President Vucic proposed the creation of a “Balkans mini-Schengen” area after vowing that Serbia would remain “militarily neutral” (i.e. it would not join NATO) and signing a trade deal with Russia’s Eurasian Union. The idea, in short, was to create a border-free area similar to the EU’s Schengen zone. Since the lack of an agreement on Kosovo is keeping Serbia out of the EU, he offered to substitute EU integration with a plan for regional integration.

However, Kosovo refused to take part in the initiative. And while other countries sent their heads of governments to summits on the subject in Novi Sad, Serbia and Ohrid, North Macedonia in October and November 2019, respectively, Montenegro sent only its economy minister. At the December 2019 regional summit in Durres, Albania, Montenegro did send President Milo Djukanovic. However, following recent attacks by Serbian ultranationalists at the Montenegrin embassy in Belgrade, it now looks unlikely the country will participate in the next summit.

Why would these countries integrate with one that is anti-NATO, has Russian troops on its territory and is allied with the Eurasian Union?

Since 1998, several similar regional projects have been proposed, including BAFTA (a Balkans free trade area), the “Balkans Benelux” and the Western Balkans 6. Serbia, however, had always opposed such initiatives. Moreover, two regional integration initiatives are already functioning: the Central European Free Trade Area (CEFTA) and the Presidential Forum, which includes the presidents of Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and North Macedonia. Serbia, however, blocked Kosovo from joining the former and boycotted the latter because it included Kosovo. Serbia’s official map for its “mini-Schengen” simply ignored Kosovo as a separate state, and showed it as part of Serbian territory. How could Belgrade lead integration in the region without recognizing one of its six states?

Moreover, how could this plan, led by a state that vowed to stay out of NATO, work with other states who are members of the alliance (Albania and Montenegro), soon to be members (North Macedonia) or with NATO troops stationed on its territory (Kosovo)? Why would they integrate with a country that is anti-NATO, has Russian troops on its territory and is allied with Russia’s Eurasian Union? Though the Russia-Balkans summit encouraged regional integration partially by claiming that it would help economic growth, joining transatlantic structures is clearly more beneficial. Montenegro, for example, saw its foreign direct investment rise twofold immediately after joining NATO.

One of Serbia’s goals with the proposal was gaining access to seaports. It is the region’s largest economy, but has been landlocked since Montenegro broke away in 2006. The mini-Schengen deal could have given it access to the Adriatic and Ionian seas (through Montenegro and Albania), and also to Greece, with its ports on the Aegean (through North Macedonia). It could have opened up more economic influence in the region for Moscow through Serbia, which has a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Union.

Most of all, the Balkans mini-Schengen plan would have halted a new geopolitical configuration wherein the four countries of the “Adriatic Balkans” – Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and North Macedonia – come under the NATO umbrella while the “Danube Balkans” countries of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, remain outside it.

Scenarios

If EU enlargement is not halted altogether, then the most likely scenario is that the accession process for the Western Balkans will become a reversible one in which the goalposts frequently change. This state of affairs will keep the Balkans loosely connected to the EU, but outside of its core system. Instead of integrating into the Union, the Balkans will become a buffer zone, absorbing migrants from the Middle East and Africa before they reach EU borders.

As an alternative to accession, the EU is likely to encourage Balkan countries to integrate more among themselves. It will be a dangerous game, since such initiatives could give Moscow, through Belgrade, larger influence throughout other countries in the region, including new NATO members.

Another scenario would see Belgrade convince other states in the region to adopt its policy of “neutrality.” This is less likely, of course, because two countries are already NATO members and one is about to join, and also because Belgrade’s claim of “neutrality” rings hollow with a Russian base on its soil. However, if the EU again delays the start of accession negotiations for Albania and North Macedonia in May this year, this scenario will gain plausibility. It is easy to see Russia offering membership in its Eurasian Union to the countries spurned by the EU.

Washington will be strongly opposed to such a scenario, and will find ways to keep North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania and Kosovo on a pro-Euroatlantic path. If it cannot turn Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina more toward Western structures, at least it can prevent Moscow from using its Balkan “pillar” of Serbia as a tool for expanding its Eurasian Union into the rest of the region.

Sometime early this year, North Macedonia will become the 30th member of NATO. Afterward, the only country on Serbia’s border that will not be a member of the alliance will be Bosnia and Herzegovina. This strong NATO presence in the region will do much to keep the countries on a Euroatlantic trajectory, even if European Union membership remains out of reach.

Leadership changes in Europe (the new European Commission which has just been installed) and the United States (the presidential election in November) will prove crucial. A clearer picture of the Balkans’ European future is unlikely to materialize until 2022.