The EU presses pause on Western Balkans enlargement

President Emmanuel Macron wants to put EU expansion on hold and the European Commission has downplayed any potential for Western Balkans countries to join the bloc soon. Accession now only looks possible by 2030 at the very earliest, and the wait could have disastrous effects for the region.

In a nutshell

- The EU is again pushing to delay Western Balkan membership

- The region is not helping itself by failing to tackle corruption

- It will be at least a decade before any new countries join

- By then, enthusiasm for membership may fizzle out

The June 2019 European Council summit poured cold water on the ambitions of six Western Balkans countries that want to join the European Union, dashing hopes that any state in the region could accede before 2030. Earlier, Brussels had talked of 2025. The EC again delayed the start of accession negotiations for North Macedonia and Albania, barely acknowledged the progress Montenegro and Serbia have made in their negotiations and practically ignored Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, leaving out any mention of a path toward their eventual accession.

The EU has applied a 2+2+2 approach to the region: there are two serious candidates (Montenegro and Serbia); two “coupled” pending starters (North Macedonia and Albania); and two questionable candidates (Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo). Kosovo remains without any visa-free regime for entering the EU.

‘Deeper before wider’

An EU-Western Balkans summit that had been scheduled for July 1 in Paris was postponed until September. Furthermore, French President Emmanuel Macron did not participate in a summit with regional leaders in Poznan, Poland, on July 4-5. He has declared publicly that he opposed any enlargement before institutional reforms are made in the EU.

President Macron’s EU policy – “deeper before wider” – has essentially delayed enlargement by yet another decade and will likely bring significant geopolitical consequences for the region. Tired of receiving the cold shoulder from Brussels, these six countries could all gradually go the way of Turkey: shunned by the EU, they will shun it back.

These countries could all go the way of Turkey: shunned by the EU, they will shun it back.

Their already fragile economies will have to endure a decrease in foreign direct investment (FDI), an increase in emigration to the EU and a strengthening of authoritarian and oligarchic regimes. A quarter of the region’s population has already left, and half of the young people still there intend to move abroad. A recent Balkans Barometer study showed that more than 60 percent of Western Balkans citizens are worried about unemployment and 47 percent about the economy in general. Only 50 percent are satisfied with their governments, while 70 percent express a lack of confidence in the rule of law.

Shift in focus

In 2004, the EU underwent considerable expansion, bringing in 10 new countries. Bulgaria and Romania joined in 2007, while Croatia acceded in 2013. After that, the enlargement policy went into a lull.

Geopolitics had mainly driven the expansion process. After integrating with NATO, former Warsaw Pact states of Central and Eastern Europe were brought into the fold, along with two Mediterranean island states (Malta and Cyprus) that had been strategically important during the Cold War. The pause since has resulted from a shift in EU policy focus from geopolitics to technical issues.

The geopolitical side has been left to NATO. The alliance has already integrated Albania and Montenegro, while North Macedonia will join soon. The EU has focused on political technicalities. This shift explains why Albania, already a member of NATO for 10 years, has yet even to begin EU accession talks.

Facts & figures

Waves of EU enlargement

The EU’s strategy change stemmed from a lesson Brussels learned from the latest wave of expansion. By allowing geopolitical factors to dominate enlargement decisions, some new members were allowed in that did not fulfill the so-called Copenhagen (political and economic) and Madrid (administrative) criteria. Some considered Bulgaria, Romania and Cyprus less prepared than the current candidates from the Western Balkans, and the European Court of Justice has sanctioned two others (Poland and Hungary) for rule of law violations.

A decade ago, the excuses for the pause in expansion were “enlargement fatigue” and a “lack of absorption capacity.” Now, the justification is President Macron’s call for reform before expansion. Some have proposed taking expansion completely off the table. French MEP Nathalie Loiseau, for example, has suggested that because the Western Balkans countries are “not at all ready” for EU membership, the bloc should instead adopt a “close partnership” with them.

Without regional stability or improvements in the application of the rule of law, EU accession for the Western Balkans is unlikely soon. Such justifications are behind the curious case of North Macedonia, which prior to its deal with Greece on its name, was only being held out of accession talks by Athens. Now that Greece has dropped its objections, Skopje faces three new vetoes to starting negotiations. It is also unclear when Albania’s accession talks could begin.

The most likely scenario is a decade-long delay of the integration process, due to three main obstacles: politics in the member states, Brussels’ bureaucracy and powerful interests in the Western Balkans. Profiting from the lack of reform, the elites in the region can pretend to want EU membership. Brussels can pretend to want those countries in the club.

Accession even by 2030 seems unlikely.

At this rate, accession even by 2030 seems unlikely. Croatia needed seven years for its accession negotiations alone – other countries in the region can expect theirs to last much longer. Montenegro has closed only three out of 35 negotiation chapters after six years. Serbia has only closed two in five years. Albania and North Macedonia have still to begin their talks, while Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina are not even official candidates yet.

Banana republics in the Balkans

The lack of progress toward EU membership is having an impact on the internal dynamics of Western Balkan countries as well. Widespread state capture by powerful interests risks pushing these countries into failed-state territory: politicized judiciaries, corrupt officials and nepotistic administrations are the norm. In the last decade, former prime ministers in three EU member states (Croatia, Slovenia and Romania) were convicted on corruption charges. There have been no such consequences for leaders in the Western Balkans, despite widespread corruption among political elites.

A report on North Macedonia by the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) listed 23 recommendations for fighting graft. The country is expected to submit a report on its progress in implementing them by 2020. In Albania, the process for vetting judges began two years ago. So far, 140 of 800 judges have been vetted. Fewer than 10 percent have lost their jobs due to the findings, though the chief justice of the country’s supreme court was recently impeached.

Facts & figures

Corruption in the Balkans

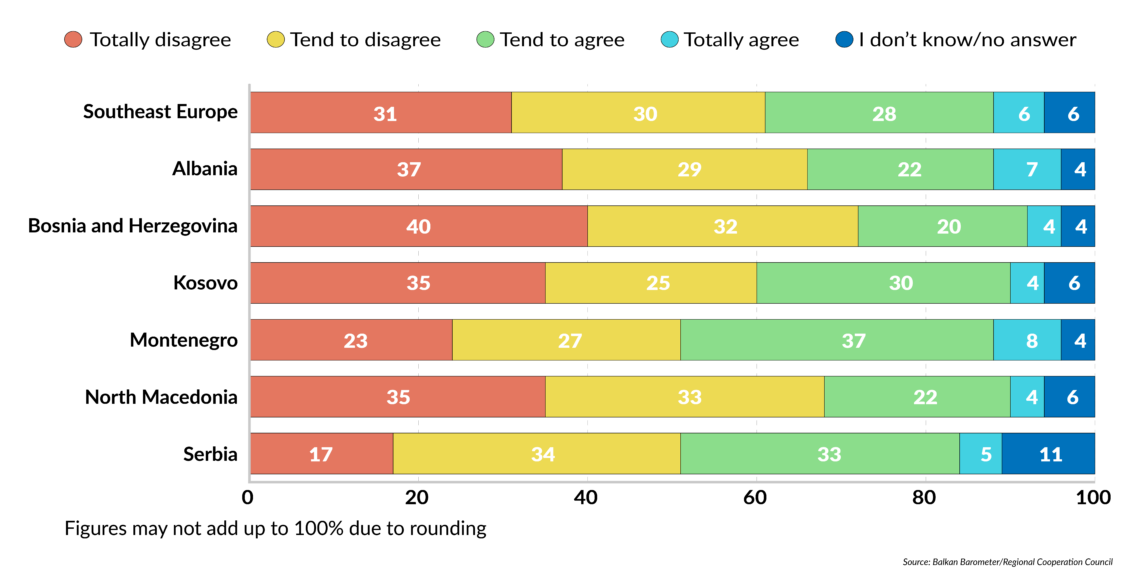

Do you agree that in your economy the government fights corruption successflly?

(share of total, %)

In North Macedonia, several key judges have been indicted, but only a few cases have proceeded to trial. Of nine judges suspected of corruption, none lost their jobs. Police vetting will start in the autumn. An anti-corruption commission was established last year, but companies owned by or linked to government ministers still tend to win lucrative contracts. The same is true for Serbia – a recent newspaper investigation found that most companies that win government tenders have links to powerful politicians.

Big corruption scandals rarely end with a court conviction, which is why people in the Western Balkans have such little faith in their judiciaries. About 57 percent of North Macedonians do not trust the Special Prosecutor’s Office, established in 2015 to fight organized crime and corruption. In the 18 cases it has brought before the court, only one of the total of 90 accused ever ended up in jail. Special Prosecutor Katica Janeva resigned on July 15 under murky circumstances. She may have been implicated in a scandal involving two businesspeople arrested on racketeering charges.

In Albania, the constitutional court has been unable to function for nearly two years due to an investigation into corruption by its judges. Can you blame the region’s citizens for not trusting the judiciary?

Economic dysfunction

Most of the 20 million people in the region are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their economies. For example, according to the Balkans Barometer survey, 69 percent of Albanians, 68 percent of Bosnians and 50 percent of Kosovars are either “completely” or “mostly” dissatisfied with their economies. This general dissatisfaction in the region is due to low salaries: the average minimum wage is eight times lower than in EU member states.

Despite being rich in natural resources, the region remains one of the poorest in Europe. Kosovo has the world’s fifth-largest proven lignite coal reserves, at about 14 billion tons. It also has abundant reserves of gold, silver and zinc. Serbia has vast coal reserves too, while significant oil and gas deposits were recently discovered in Albania. None of this can be exploited without foreign investment, which will not arrive until businesses feel like they can trust the legal systems in the region.

The region attracted only about $7.4 billion in foreign direct investment last year.

According to the United Nations’ 2019 World Investment Report, the region attracted only about $7.4 billion in FDI last year. Serbia saw a nearly 44 percent rise in FDI between 2017 and 2018, to $4.1 billion. The figures across the rest of the region were far less impressive. FDI to Montenegro even decreased by 12 percent to a meager $490 million. Bosnia and Herzegovina attracted just $468 million, North Macedonia $737 million and Albania $1.3 billion. Without more FDI, countries in the region will be unable to improve their economies.

Membership of the bloc would also increase the flow of EU funds to the region. Bulgaria’s case is illustrative: it has made use of some 30 billion euro in EU funding. The Balkan countries are allotted “instrument for pre-accession assistance” (IPA) funds – but shortages in internal administrative and institutional capacity limit their ability to utilize these funds. For example, North Macedonia used up only 30 percent of its designated IPA rural development funding. Corruption also siphons off EU money meant for development.

The Berlin Process offered an alternative for Western Balkans countries to finance infrastructure and energy projects. At the Poznan summit, an EU grant of some 180 million euro was promised for these purposes.

The general climate of insecurity in the Balkans has prompted a wave of emigration, on the one hand causing a brain drain but on the other providing a source of income to the region. Both Kosovo and North Macedonia receive about 1 billion euros in remittances annually.

In all six countries, the chasm between the rich and poor is rising, mainly because of corruption and the fragile state of their economies.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that President Macron’s opposition to EU expansion will keep the Western Balkans’ accession process on hold for another decade. With German Chancellor Angela Merkel leaving the picture, there will be no European leader left to challenge Mr. Macron and push an accession agenda forward. Even with Ms. Merkel at the helm, the date for entry kept getting pushed back, first to 2020 and then to 2025. This enlargement process is already the longest in the EU’s history, having lasted 20 years since the 2000 Zagreb summit kicked it off. President Macron’s “deeper before wider” policy will further dampen any remaining enthusiasm for EU membership in the Balkans.

The accession of North Macedonia and Albania will likely be vetoed by Greece, after the July 7 victory of the conservative New Democracy party there. Its leader, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, opposes the Prespa Agreement that ended the years-long dispute with North Macedonia over its name. Greece’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Nikos Dendias is from the island of Corfu, just off the Albanian coast and near undersea oil and gas reserves which are the subject of a territorial dispute between the two countries.

Personnel changes within EU institutions will slow down the process as well. The new High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, will mediate the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue even though he hails from Spain, a country which does not recognize Kosovo. Whoever becomes the new enlargement commissioner will also play a crucial role – if the post is not eliminated.

Under this scenario, the EU’s “pause” strategy would create integration fatigue in the region and fuel anti-EU sentiment: a dream come true for powers that oppose the Euro-Atlantic alliance.

The geopolitical consequences of a long pause are difficult to predict, considering there are three other players involved: Russia, China and Turkey. However, any considerable change of course is unlikely in the short- to medium-term. The EU will spend the next six months focused on institutional changes after this past summer’s European elections. Starting next year, President Macron will take over for German Chancellor Angela Merkel as the de facto leader of Europe.

A less likely scenario would see the EU quickly change its position on the Western Balkans. Germany and France would lead a drive to resolve the Kosovo-Serbia dispute within the next two years, opening a path for regional integration into the EU. During a visit to Belgrade in June, President Macron announced he would invite delegations from Serbia and Kosovo, as well as Chancellor Merkel, to Paris to tackle the issue.

Brussels’ turn toward a more proactive enlargement policy, however, remains an improbable scenario. The EU will keep expansion on hold, at least until 2030.