Biden’s energy policy: Clinging to old tracks

The Biden administration’s early days in office prompted many to say that the American oil and gas industry was condemned. However, Washington has yet to make a move that would seriously threaten producers – or signal a drastic change in Biden’s energy policy.

In a nutshell

- Many believed Biden would tackle the fossil fuel industry soon after taking office

- So far, however, no harsh measures have been imposed – certainly no fuel tax

- Biden's energy policy will likely seek to balance economic interest and public opinion

Soon after assuming office, United States President Joe Biden signed executive orders and made announcements that led environmentalists to declare that the oil and gas industry would soon be dead and buried. The fight against climate change is one of the Biden-Harris administration’s four key priorities, along with Covid-19, racial equity and the economy. The new president also brought back the world’s second-largest emitter of carbon dioxide to the Paris climate agreement and suspended new oil and gas drilling permits on federal land. The White House assigned more than $2.2 trillion to green projects and promised to stop subsidizing the fossil fuels industry.

At a glance, the new administration appears much greener than the previous one. However, it is worth considering not only what was said and done, but also what did not happen. Though it is still early to undertake a comprehensive assessment, based on the current rhetoric it is unlikely that the Biden White House will spell the demise of one of the oldest U.S. industries. For fossil fuels to go out of use, they should be made more expensive. After all, it is the relative price of fuels that drives and accelerates substitution. However, to date, no U.S. president – be it a Democrat or Republican – has won an election while promising higher oil and gas prices.

The current U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm has stated, following a call with her Saudi counterpart on April 1, that the Biden administration “reaffirmed the importance of international cooperation to ensure affordable and reliable sources of energy for consumers.”

Facts & figures

Top energy producers

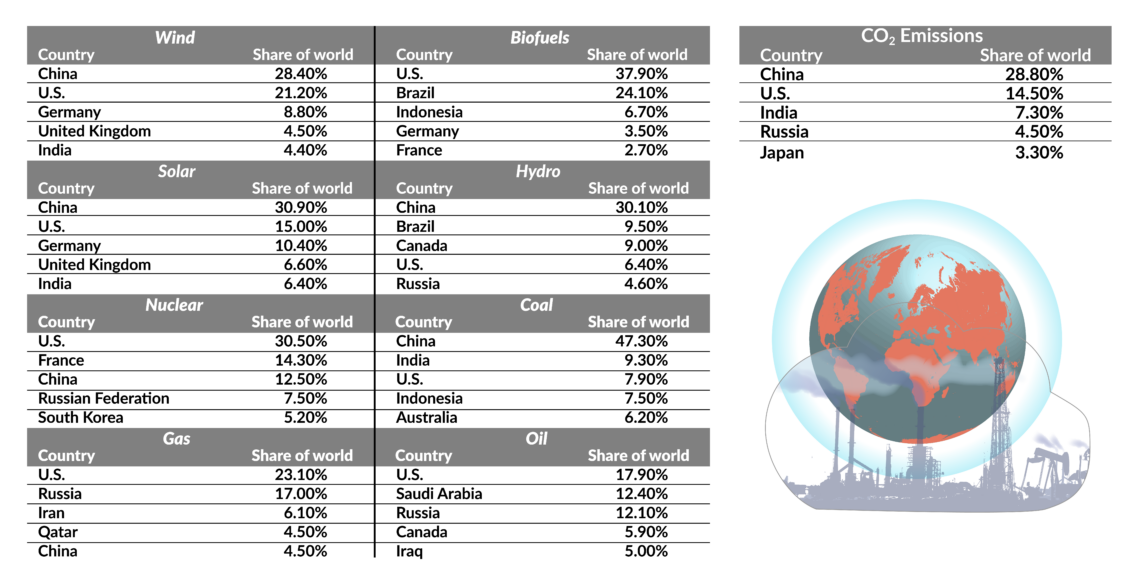

- Together, the U.S. and China account for more than 40% of the world economy.

- The U.S.’s oil and natural gas industry supports 10.3 million jobs and nearly 8% of GDP.

- China and the U.S. account for about 50% of wind energy generation.

- China, the U.S and Germany account for 55.4% of solar energy generation.

- The U.S. and Brazil account for more than 62% of biofuels production worldwide.

- China, the U.S. and India account for half of global emissions.

Fingerprints everywhere

At $21.4 trillion, the U.S. economy is the world’s largest and amounts to nearly 24.5 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP), despite accounting for only 4 percent of the population. By comparison, China, the second-largest economy, accounts for 16.4 percent of the world’s GDP and 18 percent of its people. The U.S. is also among the top five producers of every single fuel.

The U.S.’ energy intensity – broadly measured as the units of energy used to produce one unit of GDP – is high. Typically, a higher measurement means less efficiency, and the U.S. is less efficient than many other developed economies, particularly in Europe. For comparison, in 2015, American energy intensity was 0.111 koe/$2015p (kilogram of oil equivalent per GDP dollar at constant exchange rate and purchasing power parity)compared to 0.059 in the United Kingdom, 0.071 in Germany and 0.079 in Japan. China stands at 0.128, but its economy relies more on the industrial sector, which entails a higher energy use.

To the electorate, squeezing the fossil fuels industry would surely prove more appealing than fuel taxes.

Several factors can lead to improvements in efficiency, and government regulations play an important role. For example, in the transport sector, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, introduced in the U.S. in 1975 after the 1973-1975 oil price embargo, helped improve the fuel efficiency of cars and trucks produced for sale in the country. These standards are expected to be tightened under President Biden – a continuation of Mr. Obama’s legacy after a relaxation under the Trump administration.

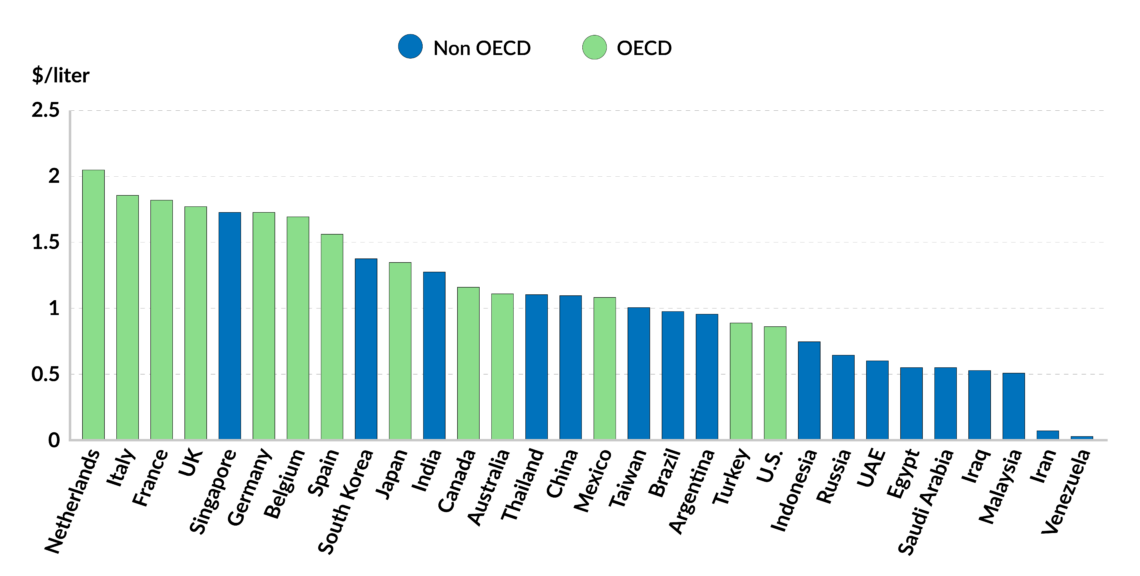

Despite having been in place for nearly five decades, the measures continue to attract significant controversy. While they have contributed to improving fuel economy, the average fuel consumption of newly registered light-duty vehicles in the U.S. continues to be above the global average. Countries that outperform the U.S. in this respect are those that impose fuel taxes.

The U.S. is one of the few wealthy economies that does not have such a tax; its practice is more aligned with what is typically found in major oil-producing developing countries. In the new administration Biden’s energy policy has shied away from any attempt to make transport fuels more expensive. Instead, it has opted for efficiency regulations and promoting electric vehicles, which is unlikely to prompt a significant transformation of the transport sector, or at least, not a speedy one.

Facts & figures

Subsidies out

To the electorate, turning the heat on the fossil fuels industry would surely prove more appealing than fuel taxes. This approach is trendy at the moment when governments’ budgets are tight. The general public is rarely opposed to squeezing more revenues from oil and gas companies, be it in the U.S. or elsewhere.

In a speech given in January this year, President Biden said, “I don’t think the federal government should give handouts to big oil to the tune of $40 billion in fossil fuel subsidies. And I’m going to be going to the Congress asking them to eliminate those subsidies.” A similar statement is made in the president’s infrastructure program, though it appears at the very end of the lengthy document and offers no additional precisions.

Former President Obama had expressed similar intentions. In 2012, he said, “Right now, $4 billion of your tax dollars subsidize the oil industry every year – $4 billion. They don’t need a subsidy. They’re making near-record profits… It’s outrageous. It’s inexcusable. And every politician who’s been fighting to keep those subsidies in place should explain to the American people why the oil industry needs more of their money – especially at a time like this.” If President Biden’s figures of $40 billion in fossil fuel subsidies are accurate, then clearly not much progress has been made to date.

The U.S. generally has lower headline tax rates than some competing oil and gas areas.

Despite the popularity of eliminating production subsidies, especially in political circles, the measure remains highly controversial. Unlike consumption subsidies, which are much better understood, there is no consensus on what constitutes a fossil fuel subsidy and how to measure its monetary worth and impact. Each study takes a different approach, and estimates vary wildly. The fiscal regime that applies to oil and gas activities contains a wide range of instruments and measures that are different from those that apply to the rest of the economy. Certain tax incentives within an overall upstream fiscal regime, for instance, are often confused with or asserted to be a subsidy, even though the government’s take from the industry is higher than from other economic sectors.

Eliminating subsidies would probably be welcome, but an enlightened and transparent discussion would require the government to adopt a clear definition of what it classifies as subsidies. Furthermore, although the U.S. generally has lower headline tax rates than some competing oil and gas areas, its fiscal regime is more regressive; the government ends up taking more revenues from less profitable projects, and vice versa. Here too, attention is required.

As for the suspension of new oil and gas leases on public land and in federal waters, it is generally agreed that the step will have only a marginal impact on domestic production. President Biden’s energy policy entails a declaration that his team would “review and reset the oil and gas leasing program.” This intention may not be as threatening as some have portrayed it. It could simply mean that the current, unnecessarily bureaucratic leasing program will be streamlined.

Facts & figures

Biden’s energy policy: A subtle balance

By trying to keep energy prices down to please American consumers in the near term while penalizing the oil and gas industry for the sake of greening the economy, President Biden is trying to face two ways at once.

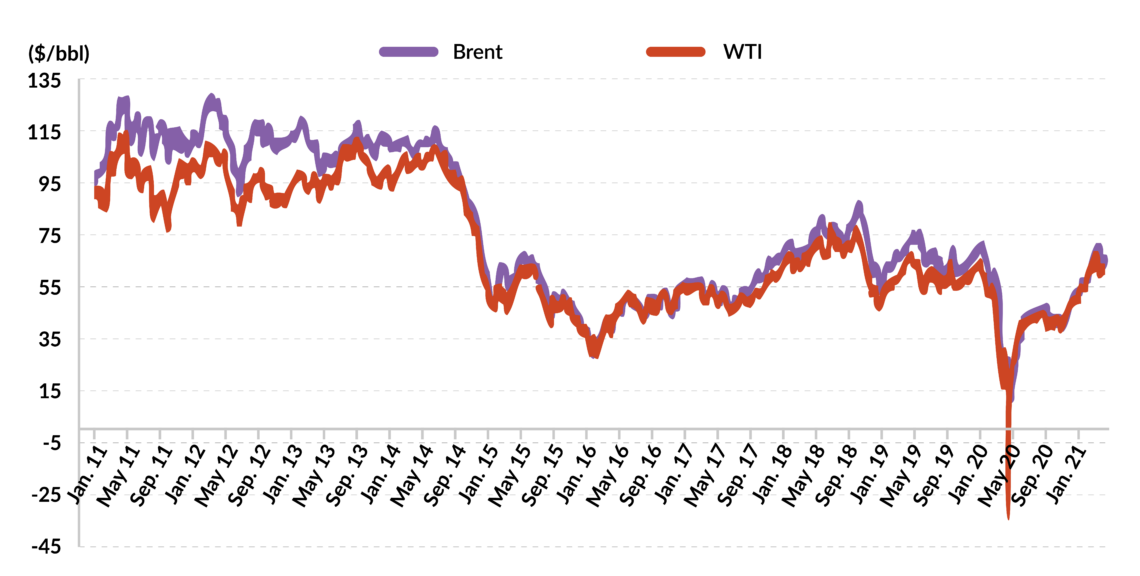

Although it remains the world’s largest oil consumer, thanks to the shale revolution the U.S. has gone from being the world’s largest oil importer to its biggest oil and of gas producer and a net exporter of both. This unique position means the country has two key stakeholders to consider: the consumers and the producers. Finding the right balance will be a considerable challenge.

Mr. Trump tried to reach this equilibrium, although he was seen as pro-industry.

Former President Trump tried to reach this equilibrium, although he was seen as pro-industry. President Biden gives the opposite impression, but he will likely seek to maintain this balance for the foreseeable future. Former President Obama promised in his 2008 inauguration speech to harness the wind and the sun “to fuel our cars and run our factories.” Still, during his term, the American shale industry blossomed, and with it, global oil prices moved from a higher price band to a lower one, benefiting U.S. consumers. It also gave Washington greater leverage in foreign affairs. The White House’s tougher tone toward the Middle East and Russia is an indirect consequence of lower reliance on oil and gas imports.