The Biden presidency and its impact on the Western Balkans

The change in U.S. leadership could have a significant impact on the Western Balkans. The Biden administration’s plans to be more engaged in European affairs could give new life to efforts aimed at pulling the Western Balkans into the Euroatlantic orbit.

In a nutshell

- President Biden will have a multilateral foreign policy

- He will likely work with the EU on Kosovo-Serbia peace

- The many other challenges on his plate could get in the way

The change in leadership of the United States is likely to have a significant impact on developments in the Western Balkans. President Joe Biden has signaled that his administration will favor engagement and multilateralism – a crucial shift from the “America First” policy of his predecessor, Donald Trump.

The Biden team is expected to put a much bigger focus on Euroatlantic cooperation – a departure not only from Trump-era policies, but also the more hands-off approach of former President Barack Obama. In the Balkans, this will likely be reflected in a stronger push toward finally concluding peace talks between Kosovo and Serbia, as well as a drive to keep Bosnia and Herzegovina united and functional.

Kosovo and Serbia are the last two Balkans states that have not signed a peace treaty with each other. Relations between them have been hostile for more than a century, since the Serbian Kingdom’s annexation of Kosovo in 1912. The animosity continued due to the repression of Albanians in communist Yugoslavia and under the brutal rule of Slobodan Milosevic in the 1990s. The Kosovo War, from 1998 to 1999, was followed by NATO intervention and by the United Nations administration. On February 17, 2008, Kosovo declared independence, which the International Court of Justice in 2010 found did not violate international law.

The goal of Serbia-Kosovo normalization remains far off.

Serbia, however, has not recognized the Republic of Kosovo, claiming the declaration violated its own constitution. The European Union introduced a process for normalizing relations between the two states, but despite efforts like the EU-sponsored 2011-2020 Brussels Dialogue and U.S.-led discussions in 2019-2020, that goal remains far off.

Multilateralism vs. unilateralism

In 2019, after two years during which the Brussels Dialogue had been on pause, the Trump administration moved forward without the EU to push for Kosovo-Serbia talks. This resulted in an “economic normalization” deal. It did not include mutual recognition and did not address the most contentious issues between the two states. Instead, it provided a broad framework, which apart from cooperation on economic matters included provisions to remove equipment provided by untrustworthy vendors (i.e., China) from their 5G network, designate Hezbollah as a terrorist organization, and diversify their sources of natural gas. The deal was a preelection foreign policy win for the Trump administration, and put both states’ policies more in line with Washington’s.

After President Trump was defeated in the November 2020 election, however, doubts over the agreement arose. Serbia had gained closer ties with the U.S., but some worried President Biden would not be as friendly to Belgrade as his predecessor had been. In Kosovo, opposition parties railed against the deal for having weakened the republic’s position vis-a-vis Serbia. In December, Kosovo’s constitutional court declared that Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti’s government was illegitimate, potentially meaning that he had not had the authority to sign the deal.

The EU, for its part, claimed that many of the measures agreed upon in the deal had already been included as part of previous EU-backed negotiations. It also made clear that it expected Serbia and Kosovo to return to the Brussels Dialogue to resolve the most difficult political issues between them. The talks could restart in the summer of this year.

It is unclear what position President Biden will take on the economic agreements. The September 4, 2020 deal was neither an international U.S. treaty nor a presidential executive order. Whether he builds on them or not, he is highly likely to drive for a “comprehensive solution that will lead to mutual recognition, preservation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of both countries and strengthening of their democratic institutions,” as the State Department recently said was current U.S. policy.

President Biden is also certain to work more closely with the EU on the issue. He has made clear that he will take a less combative stance with European allies and will fully support NATO. In a foreign policy speech in early February, he declared that “America is back” to help Europe protect itself against Russian aggression. The sentiment was welcomed by both the EU and NATO.

President Biden’s foreign policy message that the U.S. “will lead the world and not withdraw from it,” has specific implications for the Western Balkans, especially through more robust engagement with NATO and a more antagonistic stance toward Moscow. During last year’s presidential campaign, he called Russia an “opponent.” Just before he took office, in November 2020, a NATO report said that Russia would remain the alliance’s “main military threat” until at least 2030.

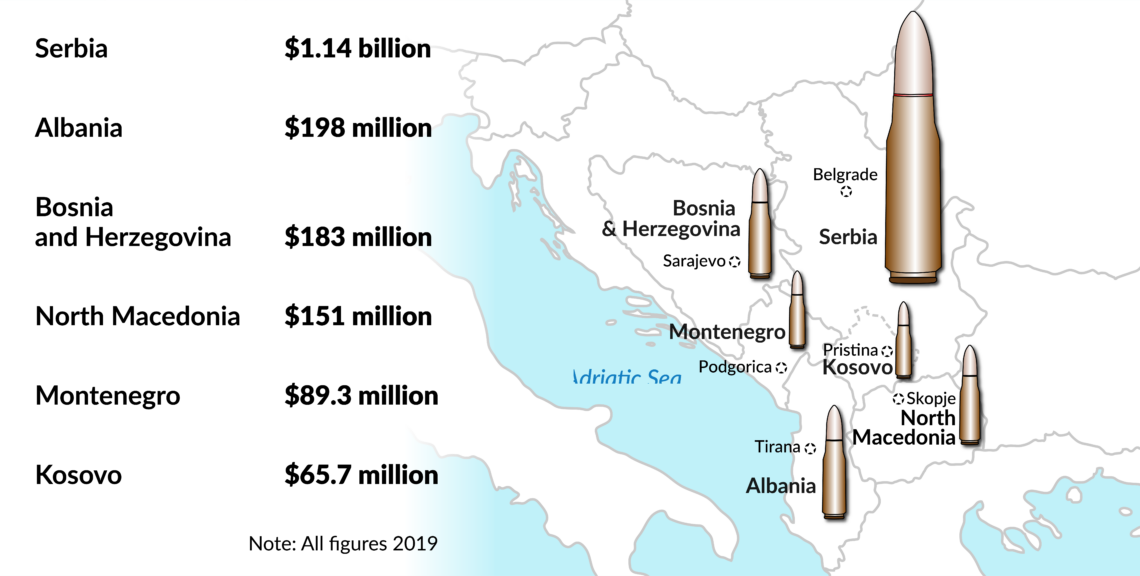

Security challenge

Conflicts in the Western Balkans could affect broader stability in Europe and the Mediterranean region. In a phone call with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, President Biden said that stabilizing the Western Balkans was among the top six urgent foreign policy matters for his administration (the others being Afghanistan, China, Iran, Russia and Ukraine). The issue is all the more urgent due to Serbia’s recent military buildup. The country now has a defense budget nearly twice that of the other five states in the region put together.

Facts & figures

Kosovo-Serbia peace and ensuring a united, functional state in Bosnia and Herzegovina are therefore not just bilateral issues, but regional security challenges. To deal with the former, Washington and Brussels could work together to create a mediated process for mutual recognition. For the latter, the new U.S. administration may push for constitutional changes that organize the state on a civic, rather than national basis, and reduce the ability of the two entities (Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) to block central government initiatives.

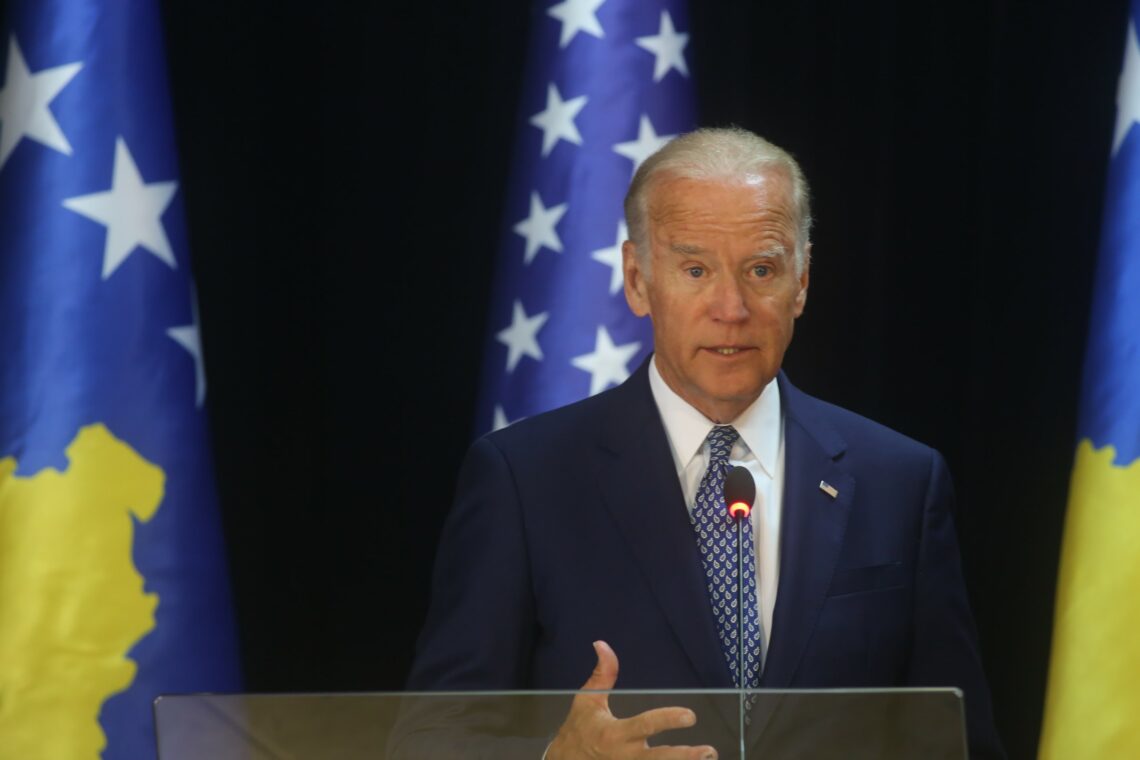

President Biden is well-known for his harsh criticism of Slobodan Milosevic.

President Biden is well-known in the Balkans for his harsh criticism of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic and his advocacy for the region during the wars of the 1990s. He has taken a clear stance that any agreement between Pristina and Belgrade should recognize Kosovo as an independent country.

He reiterated that position again in a letter to Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic in February. “We remain steadfast in our support for Serbia’s goal of European integration and encourage you to continue taking the hard steps forward to reach that aim – including instituting necessary reforms and reaching a comprehensive normalization agreement with Kosovo centered on mutual recognition,” he wrote.

Other powers

Russia and China have their own views on how the Kosovo issue should be settled, and getting these two heavyweights to go along with the White House plans will prove a tough challenge. Much of Europe, notably Germany and France, have taken a softer stance on Russia in recent years, arguing for more cooperation, rather than antagonism.

Of those two countries, Germany’s position on the Western Balkans is closest to President Biden’s. Berlin favors a comprehensive, sustainable, legally binding agreement between Kosovo and Serbia. Chancellor Merkel has stated that Serbia cannot join the EU until it has normalized its relations with Kosovo. France, for its part, wants normalization dialogue to continue, but would be satisfied with Kosovo joining the UN, even if Serbia refused to recognize it. French President Emmanuel Macron hosted President Vucic in Paris in February, after which he praised his Serbian counterpart for having come up with “innovative solutions” to the problem, though he did not specify what those were. The leaders confirmed that “normalization” of relations remained the ultimate goal.

In the first half of 2022, France will hold the rotating EU presidency and will also hold its own presidential elections. A Kosovo-Serbia deal would burnish President Macron’s record ahead of the vote.

China has shown its hand via its diplomatic and economic moves.

Russia is a traditional ally of Serbia, and has retained a keen interest in the talks between Belgrade and Pristina. After the Macron-Vucic meeting in Paris, the Kremlin released an official statement that President Putin was committed to finding a “balanced” solution that should be approved by the UN Security Council.

China has kept out of the politics of the Kosovo-Serbia talks, but nonetheless has shown its hand via its diplomatic and economic moves. It still has not recognized Kosovo, and has instead strengthened its bilateral ties with Serbia. In 2020, Serbia-China trade increased by some 30 percent and this year, China provided Serbia’s biggest delivery of Covid-19 vaccines. President Vucic has said he is “proud” of this cooperation. But there is no free lunch with China. It hopes to penetrate EU markets via Serbia (and Hungary). Its loans to Serbia have grown so large that opposition parties have begun warning that the country is entering “Chinese debt slavery.”

Upcoming elections

In the 2021-2022 period, four out of the six countries in the region have elections. Kosovo held elections in February, while Albania will have elections in April. North Macedonia will hold a vote in autumn, and Serbia in 2022.

The elections in Kosovo and Serbia will be crucial for the peace process. In February, the party led by former Prime Minister Albin Kurti won a decisive victory, giving him a mandate to renew his policy of “reciprocity” regarding tariffs on goods from Serbia, no territorial exchange and no internal federalization of Serbian municipalities.

Next year, Serbian President Vucic will face elections. Although he has declared he would never recognize Kosovo, addressing President Biden’s request could help him win a second term.

Scenarios

All this brings us to two broad potential scenarios. In the first, most likely scenario, President Biden turns a new page in American foreign policy, returning to multilateralism through various treaties and international organizations. Part and parcel of this approach will be strengthening the Euroatlantic alliance through greater cooperation within NATO and between the U.S. and EU more generally.

With the Kosovo-Serbia issue, Brussels and Washington share interests and could find ways to work together. This cooperation could even serve as a pillar on which to build renewed trust. It is likely this will mean an entirely new strategic approach, based on President Biden’s conviction that any final agreement must include bilateral recognition. Resolving the issue will address security concerns for both the U.S. and Europe – reinforcing European stability and keeping other global powers from meddling in the region.

The second scenario is more pessimistic, but also less likely. President Biden could get bogged down in his domestic priorities, and potentially other international challenges. A Kosovo-Serbia deal in this scenario would be unlikely to happen in the near to medium term.

In this scenario, Europe’s distrust of the U.S. remains high, making cooperation difficult. President Macron – whose policies are already less aligned with the U.S.’s than those of outgoing German Chancellor Merkel – takes on the mantle of European leadership. However, his priorities for the European presidency and the French elections get in the way of cooperation with the U.S. on Western Balkans issues.

As China expands its economic presence in the region, Russia and Turkey also become even more involved.