Blockchain: An agent of profound change

Blockchain technology could profoundly change how governments operate. Its ability to quickly and securely transfer assets could disrupt current institutional frameworks and decentralize power. Thus, it is unclear how far states will go to support the technology, even though it could make their economies more efficient.

In a nutshell

- Blockchain applications will decentralize institutional power

- The role of non-state actors could grow

- The changes could have a big impact on economic centers

The transfer of money, assets and resources is a key factor in determining geopolitics and the distribution of power. Currently, there are national and supranational institutional systems that provide frameworks for these transfers. Without a strong legal system (including laws, attorneys, procedures and judges), ownership disputes cannot be resolved. However, blockchain technology has the potential to change this state of affairs and put into question this institutional sovereignty by distributing these decades-old frameworks among decentralized actors and computer networks. The technology has therefore gained the interest of governments, as well as international organizations and supranational actors.

Blockchain and Bitcoin

Technically speaking, a blockchain is a decentralized ledger for transactions which is protected against manipulation by cryptographic functions and a series of interconnected mechanisms. For example, in the Bitcoin network, all transactions are made visible and verifiable for all participants in the network, so no transaction history can be lost or added later. At the outset, blockchain technology was developed as an alternative for creating a technological replacement for the interpersonal trust between transaction parties.

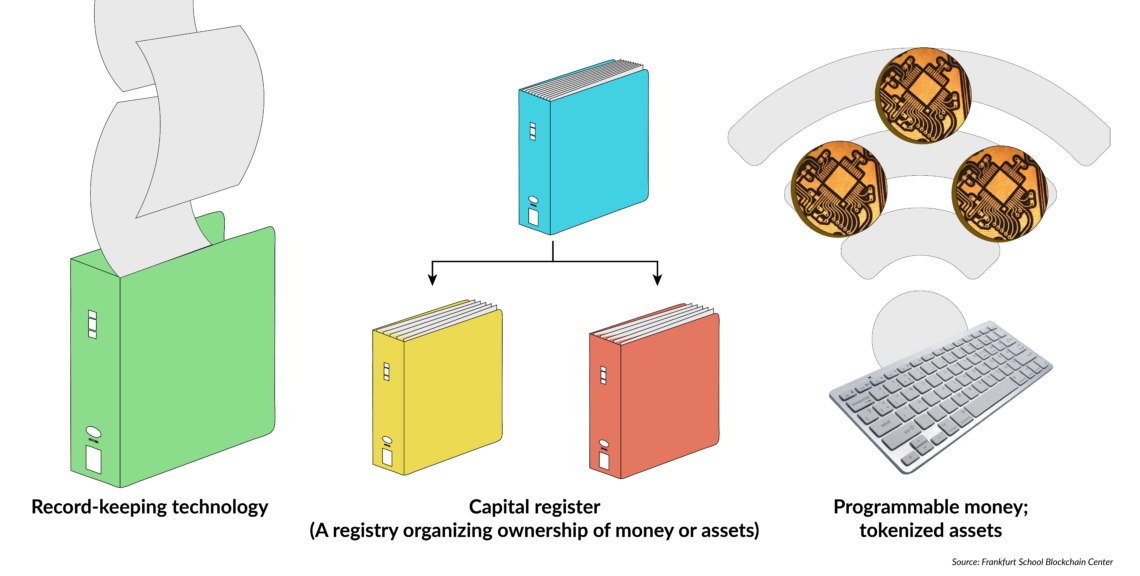

Nontechnically speaking, a blockchain provides a joint register to organize things like assets. The record-keeping uses collective multiparty accounting and cryptography. Using these features, an agreement on the approval of a transaction is concluded by all participants within the network. An entity to organize the system and provide oversight is no longer needed. For the financial market, blockchain technology fulfills the function of a capital register, organizing the ownership and transfer of any kind of digital value, such as money or assets, enabling forms of programmable money (for example, Euro-on-Blockchain) and tokenized assets.

Blockchain technology could redefine today’s framework for value and money.

It is not only secondary institutions such as retail or private banks that can use this technology to increase the efficiency and security of transactions. Central banks and other primary elements of the monetary system can do that too, as well as digitally represent purchasing power. Until now, only analog assets like securities and money, which are still often paper-based, represented purchasing power and value. Blockchain technology will digitize the latter, leading to a new breadth of possibilities for how they can be represented. Blockchain technology could therefore help redefine and reorganize today’s framework for value and money. However, the monetary sphere is only a small part of the bigger blockchain picture.

Facts & figures

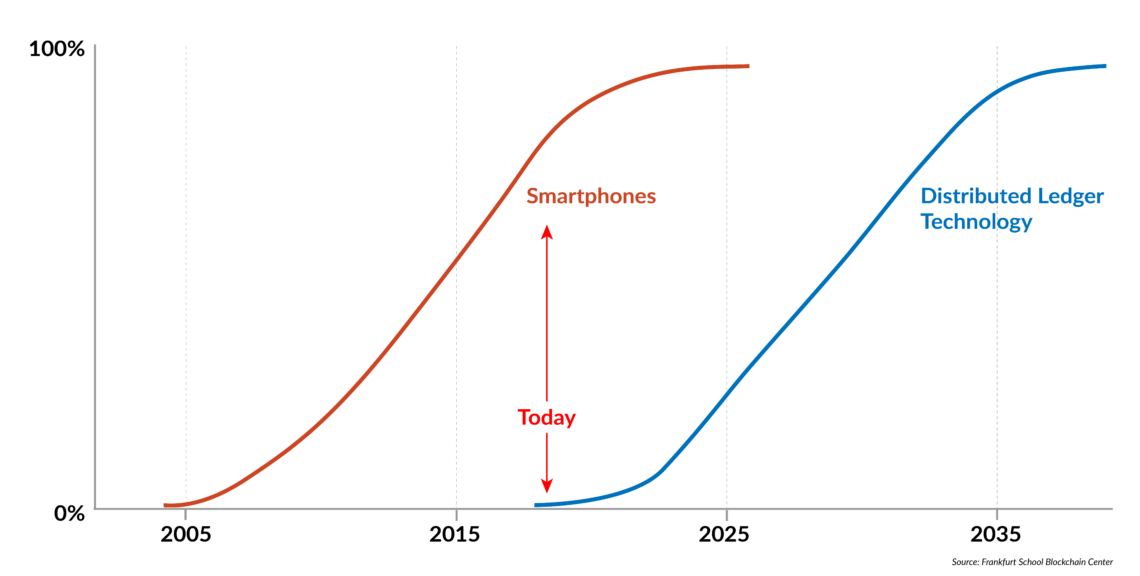

Figure 2: Estimated development of Distributed Ledger Technology

Range of possibilities

Blockchain’s uses are not limited to financial applications. They can be applied to all kinds of transactions that require transparency and stringency. In fact, anything that is organized as a register nowadays is a potential candidate to be run on blockchain. This includes money, securities, automobile registers, passports and commercial registers. As the world increasingly becomes digital, blockchain technology can help transaction processing and data-structure development in more and more applications.

At large scales, most blockchain structures require tremendous amounts of computing power, and therefore also resource consumption. Scientists and developers are often asked about how scalable the technology really is.

Blockchain is still nascent – its usability is being defined and tested, and the first successful prototypes are running. Nevertheless, the technology will see its biggest leaps in development over the next 10 or 20 years – as was the case with smartphones and the internet. Issues of technical feasibility, social acceptance and necessity will work themselves out in this period.

Facts & figures

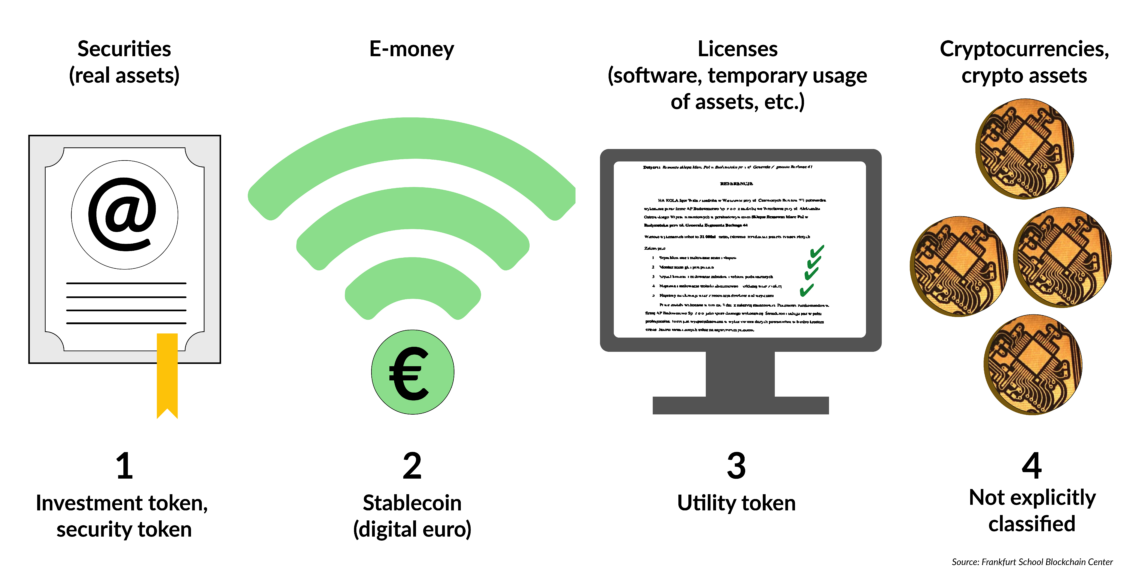

Figure 3: Where tokens have been and will be used

It is important to understand blockchain’s potential from an institutional point of view, and why it is a competitor to established systems. Blockchain technology and other Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) applications are adopted by institutions through the depiction of rights and law into technology, then embodied by a token that can take various forms (see Figure 3): an investment token (security token), a “stablecoin” that represents the digital euro or dollar, a utility token that represents certain shares or licenses, or a cryptocurrency in the classical sense. Often it is not technical factors but the lack of legal certainty that limits such applications.

The leading example of legislation that institutionalizes such technology is the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act. It includes the Token Container Model (TCM), which defines the token as a “container” that can represent certain rights. The “container load” can potentially be any right. This way, a token can digitally represent the right of ownership on a stock, a house, or on money. The TCM highlights the function and relevance of token in our future economy.

This approach uses elements of existing civil law while also providing the necessary legislation for transferring tokenized property. A tokenized right would be “sitting” on a blockchain network and would be the fundamental characteristic for business models within the digital economy. The key feature is a physical validator, which compares, verifies and synchronizes the online and offline ownership world of real asset rights. The approach ensures a high degree of standardization, but also flexibility for new technical possibilities and asset classes.

Facts & figures

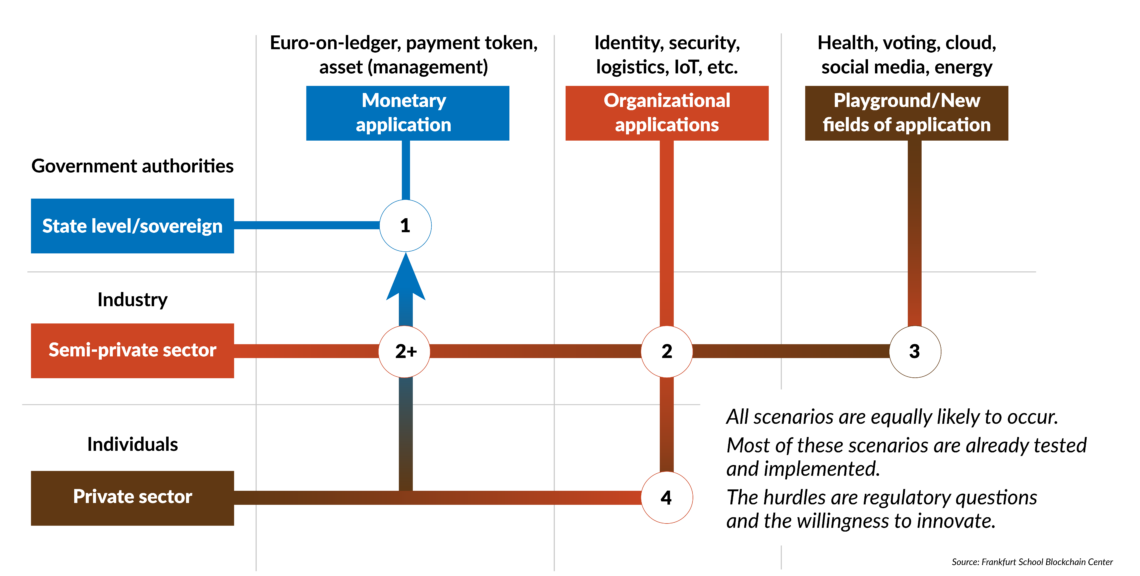

Figure 4: Example scenarios for exploration and adoption of blockchain technology

Four main scenarios can arise from the interactions of three types of actors and three application sets (see Figure 4), although other combinations are possible. The actors are the private sector (individuals without an organizational background), industry (non-state enterprises, start-ups, investors, consortia, etc.) and governments and authorities (i.e. the state itself and state enterprises).

Then there are three different sorts of applications. The first is monetary (digital money, payment tokens, asset management, crypto custody, etc.). The second covers organizational questions such as digital identity, cybersecurity, logistics and the “Internet of Things” (IoT). The third is a “playground” in which new applications can be explored, for example in elections, cloud computing, energy and dealing with fake news.

Blockchain could fundamentally change the digital representation of values and assets in a few years’ time.

First scenario

In the first scenario, a state opts to use blockchain-based solutions in monetary applications. Among such solutions are currency-on-ledger, including Euro-on-Ledger, which is all about getting the euro on blockchain systems potentially (but not necessarily) in the form of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC). The payment infrastructure does not comprise complex banking systems, but simply a blockchain system on which the euro or another official currency is denoted.

Today, the transaction of digital assets (such as money) still requires the presence of a trustworthy intermediary, for example, a bank or a stock exchange. As an “internet of value transfers,” blockchain technology could fundamentally change the digital representation of values and assets in a few years’ time.

Numerous potential blockchain applications will require payment transactions in a state-approved currency. By programming the value of a currency such as the euro into a blockchain, smart contracts will ultimately be made possible. This will be enormously important for digital business models in industry 4.0, IoT, energy, logistics and mobility. It will also make it possible to keep a secure digital record of payment transactions and asset management functions that are denoted in state-backed currencies.

The scenario is highly likely, but government institutions and regulatory hurdles are delaying it from occurring. And anyway, authorities tend to take a dim view of such projects when carried out without any state involvement (as it has become very clear in the case of Facebook’s digital currency project, Libra).

The scenarios that do not question the state’s monopoly over money creation or governmental functions are more likely

Governments and central banks are unlikely to welcome these innovations with open arms. Prominent central bankers in Europe are already demanding legislation to block such developments. However, some (like in China, Sweden and Canada) are intensely supporting research in these areas and want to establish blockchain innovations such as digital central bank money. The semi-private and private sectors can only follow in the field of monetary applications once the authorities have steered the projects into legally recognized channels.

Second and third scenario

The second, second-plus and third scenarios concern the semi-private sector: nongovernmental companies that deal with either organizational issues, or the more far-reaching “playground” applications. These include applications that aim to increase the efficiency and security of process in the fields of identity management, security, logistics and IoT, but also more experimental projects in health, voting, cloud computing, social media and energy.

These scenarios are more probable, at least in the short term, since they do not question the state’s monopoly over money creation or governmental functions. Instead, they merely compete with existing systems such as logistics chains, analog patient files in healthcare and centralized energy distribution solutions. There are already numerous start-ups that have proven themselves in these fields and deliver significant added value.

Fourth scenario

In the fourth scenario, the private sector organizes various elements from the areas mentioned above (but also monetary questions, such as peer-to-peer payments) through the use of blockchain technology itself. Individuals then take control of their own digital identity and their own payments. By owning a crypto wallet, every individual can transfer a value (in the form of a token) to other users without intermediaries such as banks or platforms like Facebook. Smart contracts and ownership claims running over the blockchain can help individuals solve these questions in the private sector. However, here there is also a regulatory hurdle. The less those processes bump up against government activity, the more likely this scenario becomes.

Varying probabilities

Of course, these scenarios cannot be separated from each other, and they have already begun to occur. This results in fruitful application possibilities, such as the combination of identity and payment or logistics and finance. The Scandinavian countries, Switzerland and Liechtenstein are more open-minded about such technologies than, for example, Germany. Yet to provide an efficient, digital public administration, states will have to be prepared to implement blockchain for monetary and organizational applications.

The key point is that DLT could make institutions and functions such as central banks, land registers and bank transfers more efficient, but only with minimal dependence on the classical organizations.

In this new value chain, banks would have to reposition themselves as intermediaries and offer, for example, a gateway to blockchain-based transaction systems for tasks such as client advisory and compliance checks, instead of just processing payments. If the authorities do not understand, accept and implement the technology fast enough, criminal actors will be able to take advantage of these structures.

Such situations could partly undermine state sovereignty. Criminal actors will naturally also use these systems to their advantage. Blockchain poses formidable challenges to the institutional architecture and the way governments are seeking to change this structure.

Big picture

When the internet’s possibilities first began to emerge, digitizing analog files and processes was considered a central element of the technological revolution. Digitization does not, however, undermine existing structures and institutions, but merely uses digital structures for already existing institutionalized concepts. Examples of this phenomenon include PayPal payments, requesting information in a land register via e-mail or a website to the authority, or documents that provide proof of ownership in PDF form.

However, blockchain technology could elevate this form of digitization even further: in most cases, its theoretical applications involve the complete technical institutionalization of new frameworks. In other words, a quasi-digital transformation of institutions.

Shifting power

In a free market, the most efficient players usually prevail. In certain areas, like peer-to-peer payments, cost-efficient, secure solutions like blockchain technology could bring about the highest degree of efficiency – the players that embrace it will come out on top. For example, a start-up using DLT could compete with an established bank for money transfers. However, public administrations can also increase security and efficiency, since governments can transfer basic tasks to blockchain technology. This especially goes for the public administration or transaction of monetary assets.

States or groups of states that push application of blockchain will be more likely to become technological leaders.

Distributed Ledger Technologies can help nearly all areas of government activity. The technical code could incorporate rules of a country’s legislative framework, digitizing rules and regulations. Smart contracts can assist the executive, for example in terms of tax collection. All those tasks could be processed through a blockchain system. The government could monitor them more efficiently and securely, especially when it comes to regulatory oversight, or preventing money laundering and tax evasion. For this to work, society must accept such changes and governments must be democratically empowered to make them.

States or groups of states that push research, application and institutionalization of blockchain will be more likely to become technological leaders. The private and semi-private sectors are especially likely to engender nnovation, but they can only do so if they are well-funded and can count on legal certainty.

The more a public administration understands and implements blockchain technology in various scenarios, the greater the degree to which institutions and enforcement power will be handed over to technology. The extent to which this should be done is not an easy question to answer. Yet to ignore or neglect the upcoming shift of institutions toward technology is dangerous and could cause our increasingly complex societies to lose out because of inefficiency.

Having such an innovation framework also provides design freedom and encourages companies to implement blockchain solutions. To take the leap to invest in such technology, decision makers need a willingness to take the risk, a technical understanding and often the buy-in of top management. Wherever the state supports these conditions, we can expect rapid steps toward building a foundation for the digital economy.

It is worth noting that the Germany/Austria/Switzerland/Liechtenstein region could take the lead role in Europe’s blockchain sector. Switzerland, Germany (with their thriving start-up ecosystems) and Liechtenstein (with the brilliant impulses of the Liechtenstein Blockchain Act) are the driving forces.

Scenarios

The effects of the scenarios as elaborated in this report cannot yet be fully predicted. What is certain, however, is that power structures will shift, becoming more decentralized and changing institutions. Institutional power and influence will be redefined, and this will have a substantial impact on the monetary and organizational landscape. However, we believe that the overall framework will still require state sovereignty and central actors but will be made more efficient by blockchain technology.

Even if many countries are striving for international regulations or governance, development of blockchain technology, like that of artificial intelligence, often occurs with a national focus on creating competitive advantages. If Europe sets its own, world-leading pace in blockchain innovation by fostering education, funding research and supporting development among the actors and application sets described above, it could become a global leader in innovation.