Scenarios for Brazil’s agricultural boom

Thanks to its unique natural resources and specialized industry, Brazil is set to reap the benefits of an agricultural boom. However, the country needs to tackle the challenges of trade liberalization, dependence on China and insufficiently diversified export products.

In a nutshell

- Agribusiness is the backbone of Brazil’s economy

- More trade agreements are needed for exports to expand

- The pandemic’s impact on agriculture will not last

Brazil is a global agricultural superpower and agribusiness is the engine of its economic growth. In only four decades, the country went from being a net importer of food into the third largest exporter, after the European Union and the United States.

The revolution began in the 1970s with the creation of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, Embrapa, a state-owned enterprise. Embrapa’s extensive agricultural research and its joint initiatives with research institutions and companies worldwide resulted in an agricultural boom. First, the Cerrado region (a stretch of savanna-like vegetation covering the central portion of the country, marked by a long dry season lasting from March through September) developed. Then, more recently, the Matopiba region, an area north of the Cerrado covering parts of the Maranhao, Piaui, Tocantins and Bahia states, also became an agricultural center.

Brazil has one of the highest agricultural total factor productivity rates in the world. In the last 40 years, the country’s production volume in farm products grew by 385 percent, while aggregate land use increased by 32 percent. Due to innovative techniques, Brazil harvests two to three crops of grains and oilseeds per year.

Home to almost 20 percent of the world’s flora, Brazil is a global leader in developing crop varieties resistant to drought, climatic changes, pests, and diseases. In addition to favorable climate conditions and water availability, the country has some of the largest arable land reserves in the world.

For decades, Brazilian agriculture has outweighed the industry in terms of productivity, but it receives much less governmental support. Farm subsidies represented only 1.7 percent of Brazil’s gross farm receipts in 2017-2019. In the United States, they amounted to 11 percent, in the EU 19 percent, and in China 13 percent, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Brazil is the world’s biggest producer and exporter of soybeans, orange juice, coffee, beef and poultry.

The agribusiness sector – including inputs, agricultural and livestock production, agro-industry and services – made up 21.4 percent of Brazil’s gross domestic product (GDP), 43 percent of its exports and 19 percent of jobs in 2019. In the first semester of 2020, food and agro-industrial exports’ share grew to 51 percent.

Brazil is the world’s biggest producer and exporter of soybeans, orange juice, coffee, beef and poultry. It is also among the largest producers and exporters of sugar, corn, pork, cotton, and cellulose, accounting for a significant share in the global exports of some of these products in 2019.

Stagnating trade

Even with the devastating Covid-19 pandemic, Brazil is expecting an agricultural boom with record grain and oilseed production of 251 million tons in 2019-2020, up 4 percent from 2018-2019, and is projecting an 11.5 percent increase in the gross value of total agricultural production this year. Brazilian government predictions show continuous growth in the production of all primary agrarian commodities during the next decade.

Most of this output will be consumed domestically, but Brazil’s overall dependency on foreign markets is growing. Today, it is already higher than 25 percent and is projected to rise to 34 percent in 10 years.

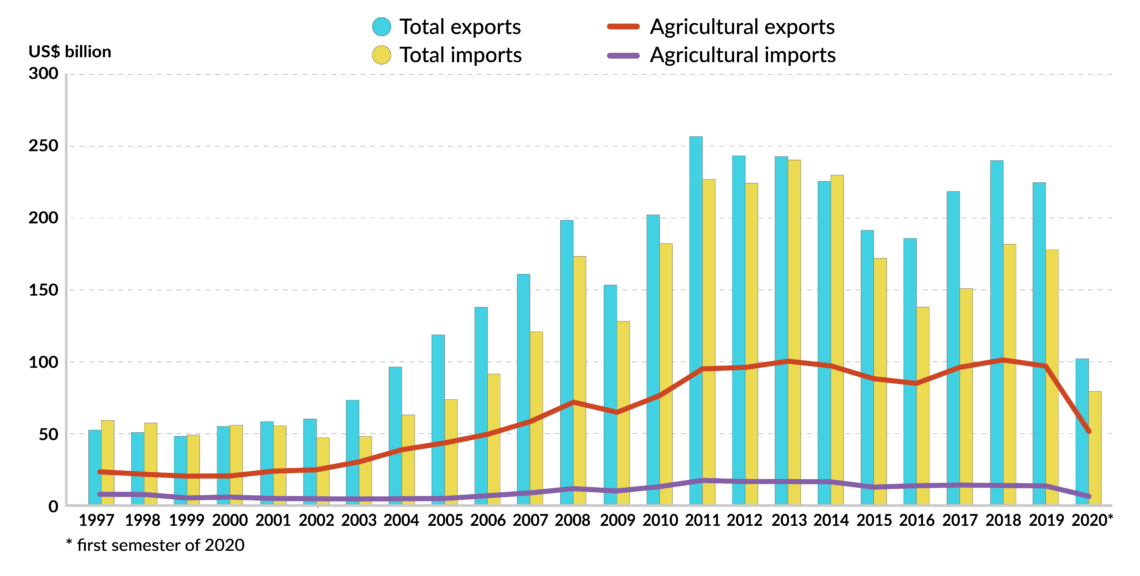

Notwithstanding the growing production, Brazil is having difficulties. Brazil’s total exports’ growth was disrupted in 2011, and since then, never recovered. Food and agro-industrial exports stagnate at around $100 billion.

The main reasons behind this state of affairs are:

- A growing concentration of exports in an exceedingly small group of primary agricultural commodities, prices for most of which declined between 2014 and mid-2019

- Significant exposure to exports to just one market – China

- Lack of trade openness

- Increasing trade restrictions and sanitary and phytosanitary requirements in export markets

- Uncertainties and disruptions caused by the U.S.-China trade conflict

High concentration

Soybeans are the country’s main export. The oilseeds accounted for as much as 20 percent of the total Brazilian exports in the first six months of 2020. Together with soybean meal and oil, this number goes to 23.5 percent. And adding the other five most significant commodities, beef, cellulose, poultry, raw sugar and coffee beans, the sum represents an incredible 38 percent of the total Brazilian sales to foreign markets.

Why did Brazilian exports become so concentrated in a small group of primary agricultural goods? In the vast majority of countries, agriculture is the sector that receives most protection from foreign competition. Agricultural import tariffs are usually much higher than tariffs for manufactured goods. Countries typically apply tariff escalations, with zero or low rates for primary products (such as basic commodities) and higher ones for processed and value-added agricultural goods.

Facts & figures

Negotiations to reduce agricultural tariffs did not advance at the World Trade Organization (WTO), so many countries resorted to bilateral trade agreements. Brazil was slow in following this trend and has few trade deals in force. With Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay, it is a part of the Southern Common Market, Mercosur. It also has trade agreements with neighboring Latin American countries (Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela), most of which are limited in scope. Outside the region, Brazil signed free trade agreements with Egypt and Israel and extremely limited pacts with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and India.

With no agreements with major importing countries, Brazilian value-added products suffer from high tariffs, making it harder for the country to compete in goods other than primary agricultural commodities.

Brazil itself is applying import tariffs that are among the highest in the world. According to the WTO, the country’s average applied import tariff was 13.4 percent in 2019. In comparison, China’s average was 7.6 percent, the EU’s 5.1 percent, Mexico’s 7.1 percent and the U.S.’s 3.3 percent.

Such high tariffs on imported goods result in a significant trade surplus, which harms the goodwill of other countries in negotiating trade agreements. This year, Brazilian agricultural exports amounted to more than eight times the imports. Trading partners complain about the lack of reciprocity in agricultural trade. If Brazil wants to export more, it needs to import more too.

Trade conflict

Since 2001, when China entered the WTO and significantly reduced its import tariffs, Brazil’s exports to the Chinese market began to grow exponentially. In 2009, China became Brazil’s largest trading partner.

In the first semester of 2020, China’s share in the Brazilian agricultural and agro-industrial exports was 42 percent, including Hong Kong. Over the same period, the EU and the U.S. accounted for only 15.6 percent and 3.6 percent of Brazil’s agribusiness exports, respectively.

Exposure for specific commodities is even bigger: in 2020, 89 percent of Brazil’s soybeans went to China. At the same time, Brazil’s share in total China’s soybean imports is expected to be around 80 percent this year. Such interdependence carries risks for both countries.

For China, dependence on just one supplier increases food security concerns.

For China, dependence on just one supplier increases food security concerns. For Brazil, there is a lack of predictability. In the escalating U.S.-China trade dispute (which now includes multiple issues aside from trade), China’s purchases of U.S. agricultural commodities have become a bargaining chip. Some of Brazil’s short-term opportunities created by the conflict may be undone by China’s concessions to ease tensions.

Moreover, Brazil and the U.S.’s growing political alignment is forcing Brazil to choose sides in the two giants’ trade confrontation. Recently, Brasilia and Washington signed a statement at the WTO calling for global action against “nonmarket-oriented policies and practices,” clearly aimed at China. Such a move may provoke retaliation against Brazil’s exports.

Scenarios

Brazil’s long-term perspectives on agricultural production and trade look promising. The growing world population, urbanization and expanding middle class in developing countries offer Brazil enormous opportunities. Sustainability and nutrition are becoming factors that increasingly influence consumer demand. The shift in global diet – toward more plant-based, varied and less processed foods – increases in the demand for fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes. Brazil’s abundant biodiversity and land and water reserves are excellent sources for such diversified supply.

The Covid-19 pandemic poses risks of temporary market disruptions, increased protectionist measures and weak demand. But it is unlikely that such shocks would negatively affect global agricultural trade in the long term.

Trade will also be vital for Brazil’s post-Covid economic recovery. Even before the pandemic, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s government set an ambitious goal to increase Brazilian foreign trade from the current 23 percent of GDP to 30 percent until 2022. It started a unilateral reduction of import tariffs, mainly for capital goods and industrial imports. Together with other Mercosur countries, it concluded negotiations of a free trade agreement with the EU (which still has to be ratified by the countries’ parliaments). Mercosur also plans to advance in trade negotiations with other major economies, including the U.S., Japan, South Korea, Canada, and the UK.

Brazil’s excessive reliance on China is unsustainable in the long term, and the country will be forced to diversify its export markets. Trade liberalization and policies aimed at addressing rising environmental and health concerns will lead to more exports and prolong the agricultural boom in Brazil.