Building a bigger BRICS

The expansion of BRICS to 11 nations will strengthen the shift to a multipolar order and challenge Western dominance.

In a nutshell

- The five BRICS nations have invited six others to join the forum

- The grouping has 3.7 billion people and 36 percent of the world’s economic output

- Major differences among the nations will limit their geopolitical clout

The recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg confirmed the transition to a multipolar order where, despite the salience of the United States and China, medium powers and regional alignments are also influential.

BRICS was first conceived in a 2001 Goldman Sachs’ Global Investment Research Division prospective report themed “Build Better Global Economic BRICs,” according to which the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China were seen as shaping the future of the world economy as drivers of growth. The group was formally founded in 2009 in the Russian city of Yekaterinburg as a forum where those four countries could cooperate on mutual interests. South Africa joined BRICS in 2010.

More than two decades after the report, the economies of Russia and Brazil have had their difficulties, but these countries remain important actors. China has become a superpower, and it is now clear that one of the foundational moments of the current world order was Beijing’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, following a long and cautious economic opening. India, in turn, which will likely have the world’s fastest-growing major economy in 2023, is well positioned to become another superpower. In March 2023, BRICS overtook the G7 in terms of its share of world gross domestic product (GDP), measured by purchasing power parity.

Read more about BRICS

The real message from the BRICS summit

BRICS’s hazy outlook

A ‘wall of BRICS’

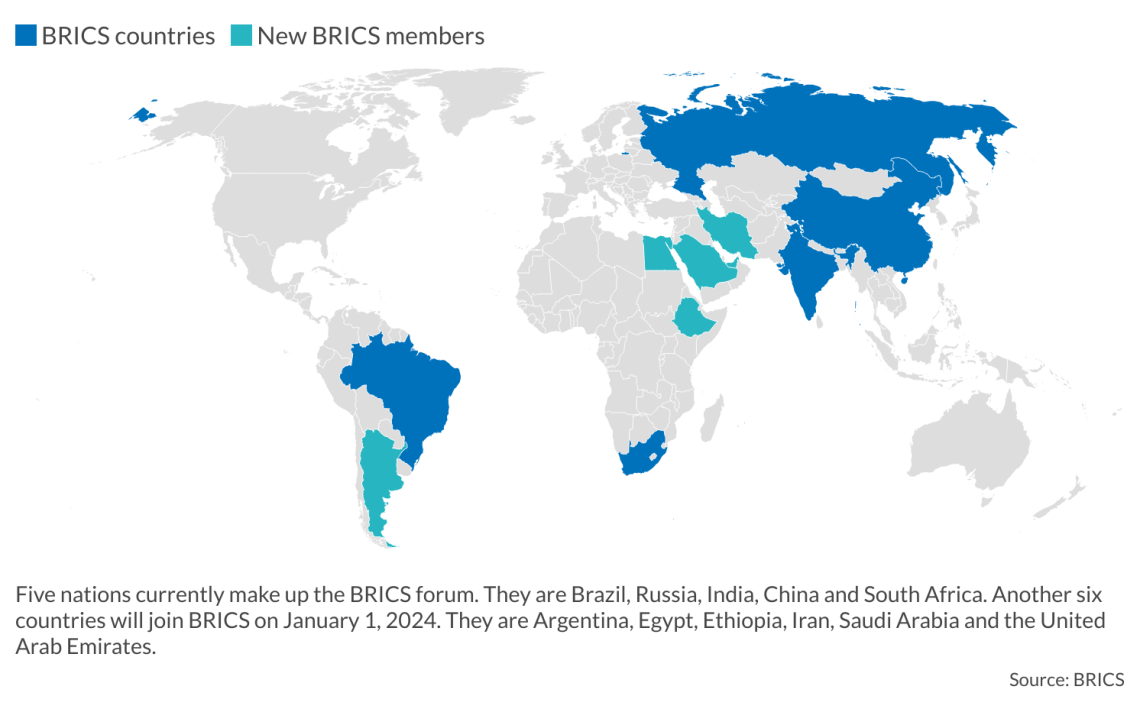

Under the theme “BRICS and Africa: Partnership for Mutually Accelerated Growth, Sustainable Development and Inclusive Multilateralism,” the 15th BRICS summit exposed one important trend and delivered one important result. First is the idea that the world order is changing and that BRICS countries are increasing their leverage within it. Second is the invitation to Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to join the group on January 1, 2024, bringing the number of nations involved to 11.

The appeal of this informal cooperation is undeniable. Before the summit, 40 countries had expressed interest in joining the group, and more than 20 had formally applied. There were, however, differences within the group regarding enlargement. While China and Russia were enthusiasts, India and Brazil were more reluctant. The final group of countries selected to join BRICS was a product of negotiations among the five members.

Four of the six new members are situated in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), a region that was not previously represented. Two of them, Iran and Saudi Arabia, are long-standing rivals. In March, Tehran and Riyadh reached a deal to restore relations, brokered by China. Algeria and Turkey, two middle powers that had expressed a strong desire to join BRICS, were left out.

With the six new members, BRICS will account for a population of 3.7 billion (almost half of the world’s population) and 36 percent of the global economic output. Moreover, the group will represent a huge portion of the world’s mining and energy reserves, production and consumption, including nearly half of global oil reserves and 42 percent of the world’s oil supply.

Abstaining from the West but not universal values

The BRICS countries have abstained from joining the West in imposing sanctions against Russia, and from explicitly condemning the invasion of Ukraine. At the end of the August 22-24 summit in Johannesburg, BRICS members expressed their support for Russia as the country assumes the chairmanship of the organization, with the 16th summit scheduled to take place in Kazan in October 2024. This nonalignment of the “rest” with the West may be a threat to the current international liberal order.

However, while the international liberal order may be in decline, the appeal of BRICS is more a symptom than a root cause. The group embodies the current period in which competition and sometimes conflict among countries and blocs are once more the driving force of the international system.

As shown in the Johannesburg II Declaration, these countries seek to counter Western hegemony by invoking the very ideas of universalism produced by the liberal international order itself – calling for the “promotion of peace,” a “fairer international order,” “sustainable development,” “justice and equality,” “human rights and fundamental freedoms for all” and “inclusive growth.”

This strategy makes it difficult to formulate an alternative discourse, as evidenced by the failure of initiatives such as the U.S.-led Summit for Democracy. Instead of citing the principle of sovereignty, BRICS countries refer to the necessity of protecting “human rights in a nonselective, non-politicized and constructive manner and without double standards,” and call “for the respect of democracy and human rights” which “should be implemented on the level of global governance as well as at the national level.” Considering the diversity of members’ cultural backgrounds and regimes (including authoritarian regimes, where some human rights are disregarded), it becomes difficult to discern the meaning of these lofty concepts and how they might be implemented globally.

The New Development Bank, formerly known as the BRICS Development Bank, is another sign not only of a return of economic competition, but of the transformation of the liberal international order itself. The global financial architecture that emerged was based on the principles of free trade, market economies, liberalization and privatization. At this point, however, these values are being supplanted by expansionist policies, regulation and intervention. The New Development Bank is a financing alternative that lends in Chinese yuan and has announced that will now also use the Brazilian and South African currencies.

Facts & figures

Multiple interests at stake

International organizations, either formal or informal, depend on the resources, power and the will of its member states.

However, while the group seeks to increase the representation of emerging markets and developing economies in international organizations, claims that BRICS represent the “rest” coming together against the “West” are simplistic. Not least because BRICS – and the new wall of BRICS which emerged after the last summit – are a very heterogeneous group.

China, the main challenger of American power, plays a leading role. Beijing sees global or regional organizations like the United Nations or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation as arenas where it can expand and consolidate its vision for the international order, through both general ideas – such as its own concepts of “development” or “human rights” – and concrete initiatives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative.

For Russia, BRICS is a platform for mitigating the effects of isolationism, including sanctions and establishing alternative diplomatic ties and trade networks.

And for South Africa, which competes for regional hegemony in Africa, the group provides easier access to global and regional powers in the so-called Global South, as well as a platform to lobby for the interests of Pretoria, and of the African continent, in international forums.

India and Brazil, in turn, are less willing to challenge the U.S. and the European Union. For them, BRICS represents an additional cooperation platform that does not replace cooperation with Washington or Brussels, as evidenced by the recent accords established between New Delhi and Washington, or by the declarations of Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva stating that BRICS should not be a counterweight to the G7, the G20 or the U.S.

There are, of course, tensions within the group. India and China are longstanding rivals and are engaged in disputes, such as the standoff along the border in the Himalayas. India has no interest in a BRICS or a world dominated by China.

Scenarios

The extent to which the new configuration of BRICS will influence the international order will be determined by a combination of factors.

One of them is the evolution of U.S.-China relations, which will depend to a large extent on the Taiwan issue. For Beijing, the One China principle remains nonnegotiable. If tensions around the status of Taiwan increase, and if Washington strengthens its support to Taipei, China will likely use its dominant position within BRICS to aggressively counter American influence. In this case, members like India, Argentina or Ethiopia would be faced with tough choices.

Another important factor is the actual ability of the organization to reach and implement decisions in diplomatic, economic or security fields. Formal or informal international organizations can expand through increasing their goals and areas of activity, their competences or the number of members. BRICS is a platform for interstate cooperation, and its resolutions depend on consensus. As it grows from five to 11 members, its resources increase, but so does the difficulty in reaching consensus. And, for the foreseeable future, persistent negotiation among various regional and state interests is expected to prevail, rather than any Cold War 2.0 logic that aligns a united BRICS against the West.

However, as Western economies experience demographic decline and economic stagnation, BRICS – by integrating some of the world’s top emerging economies and demographic heavyweights – will offer more potential in terms of economic growth. Nevertheless, concerns about the de-dollarization of the world economy may be, if not greatly exaggerated, premature. The dollar is expected to remain the primary medium of exchange and unit of account in the coming decades, and BRICS members, including China, while working to reduce their dependence, are not interested in an accelerated process of de-dollarization. Moreover, since its creation in 2014, BRICS’ New Development Bank has disbursed around $33 billion in loans, which is far less than the World Bank committed to disburse in 2022 alone.

However, BRICS may become a key forum for negotiations in areas like energy. Interestingly, although it integrates some of the world’s most carbon-intensive economies, climate change, trade and energy do not seem to be priorities, judging by official declarations made throughout the recent summit. Members are instead expected to push for the reform of international institutions, namely the UN Security Council.

Ultimately, the great advantage of BRICS is the growth potential of some of its economies and its flexible structure.