BRICS’s hazy outlook

A new geopolitical order means BRICS countries will have to reassess the organization’s mandate.

In a nutshell

- In its early days, BRICS appeared likely to benefit its members

- New tensions among China, India and Russia have stalled integration

- Membership could become less appealing for Brazil and South Africa

The idea of cooperation among the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China resulted in the formation of the BRIC bloc in 2001, with South Africa joining the group in 2010. BRICS emerged as a diplomatic and economic collaboration framework aiming to challenge Western influence in the global economic order. The group set up a development fund to finance infrastructure projects, a critical missing link in emerging economies. But now, with a geopolitical situation drastically different from that of the early 2000s, it is not obvious whether Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa will keep cooperating as a group. With no end in sight to the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine, BRICS members now have to reconsider the relevance of the body’s mandate.

An alternative to the West

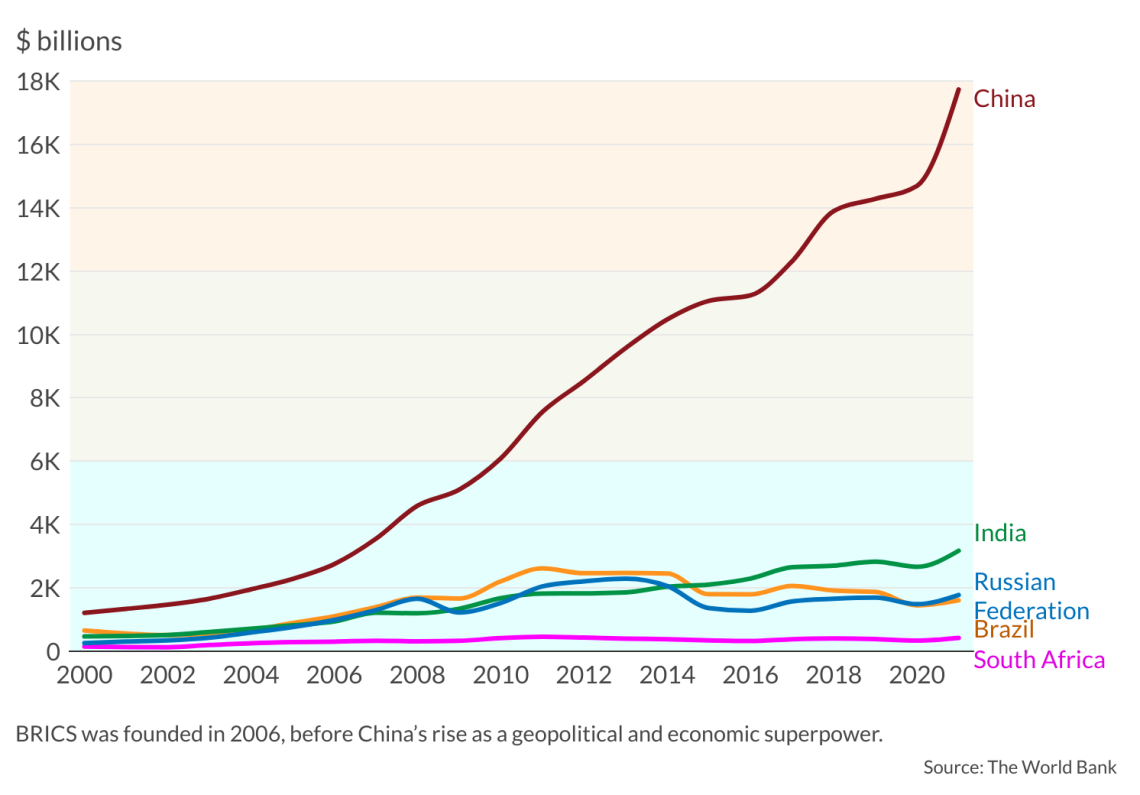

The establishment of BRICS was hailed by member states and observers as the creation of a countervailing force to the Western development agenda. The expectation was that Russia and China would lead the organization by leveraging their advanced economies to the benefit of other members.

The BRICS member states have diverging interests, with some countries in open conflict with each other.

Western countries frequently express concern about how BRICS could affect Africa’s trade with the European Union and the United States. Foreign diplomats from Western countries working in South Africa often raise the issue and argue that BRICS poses a threat to global trade given China’s clear intention to gain more geopolitical clout by expanding its economic influence.

In terms of economic power and reach, Brazil and South Africa are junior members in the BRICS pact. The two countries will likely need to weigh the potential benefits of membership against the risks of siding with Russia and China on the global stage. Much has changed since the formation of the group. Tensions between India and China have grown considerably over the border conflict in Jammu and Kashmir. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made Moscow a pariah in the West. And Beijing is facing political and economic turmoil resulting from its stringent restrictions against Covid-19.

Emerging rivalries

While China did not openly denounce Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, relations between Moscow and Beijing have become rockier. The war has brought massive economic turbulence at a global scale, including rising inflation exacerbating social tensions across different regions, including China. Russia’s prolonged expedition in Ukraine is worrying Chinese authorities. At the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit held in September this year, Xi Jinping quietly stood back as Russian President Vladimir Putin praised “the balanced position of our Chinese friends regarding the Ukrainian crisis.” But the Chinese side made no statement to support this claim, hinting at growing frustration with the fighting in Ukraine.

Facts & figures

Now focused on the task of reining in citizens’ discontent, President Xi could do without Russia’s destabilizing expedition, which compounds his problems at home. Meanwhile, South Africa and Brazil find themselves caught in China’s increasingly hostile systemic rivalry with the West. While at the time of BRICS’s creation, it still appeared conceivable that China and the Western bloc would overcome their differences and collaborate closely, several developments have deepened the rift between the two, especially Beijing’s aggressive military posturing in Asia.

Another issue is China’s strategy of funding infrastructure in countries with governments unlikely to repay the loans. This “debt trap diplomacy” – aimed at appropriating national assets in recipient countries and eventually expanding China’s strategic and military presence around the globe – is also causing concern.

BRICS heavyweight India has expressed its displeasure with China gaining control of the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka after Colombo could not repay Chinese loans received for construction. When a Chinese research vessel sought to dock there, New Delhi decried the presence of a “spy ship” in its backyard. India has come to view trade and economic relations with China as a security risk. This is pushing New Delhi to turn West, away from China and the BRICS pact. India would also like to present itself as an alternative to China for Western firms seeking safer places to expand their production. Meanwhile, African countries are also aware of the debt trap risk and talk of “economic colonialism” is increasingly becoming part of local policy dialogues.

The geopolitical climate is such that neither China, India or Russia can wholeheartedly commit to BRICS’s success.

The BRICS member states have diverging interests, with some countries in open conflict with each other. China and India’s regional conflict is weighing heavily on the organization, and meaningful economic cooperation involving the two powers is unthinkable at this stage. There is also little support for Russia to be had from New Delhi, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi declaring that “this is not the time for war.” This places the future of BRICS in serious jeopardy.

Scenarios

China is looking for a stable market for its goods, and BRICS would hardly offer such demand. What Beijing wants is further access to Western markets and consumers, albeit on its own terms. This means that the Chinese regime most likely sees BRICS not as a framework to be strengthened but as a stepping stone to global economic dominance. China is not looking to create an alternative to the Western-dominated global trade regime; it rather seeks to upstage the West and control the existing global economic order.

Through BRICS, South Africa and Brazil were hoping to gain access to global markets and grow their economies, not take sides in proxy wars. The geopolitical climate is such that neither China, India or Russia can wholeheartedly commit to BRICS’s success. This leaves Pretoria and Brasilia alone in wanting closer economic cooperation through the framework.

Both countries need these trade ties given their difficult economic situation at home. But now that the major geopolitical players within the organization are all pursuing an agenda of their own, the risks of belonging to this platform may ultimately outweigh the benefits.