Burkina Faso: Another Russia-West hotspot?

A weak central government, a fragmented military and Islamic terrorism threaten to turn the Sahel nation into a geopolitical confrontation zone.

In a nutshell

- Two military coups in 2022 highlight political instability, horrendous violence

- The nation may become the next battleground between Russia and the West

- Strict military rule is seen as a bulwark against Islamic jihadist groups

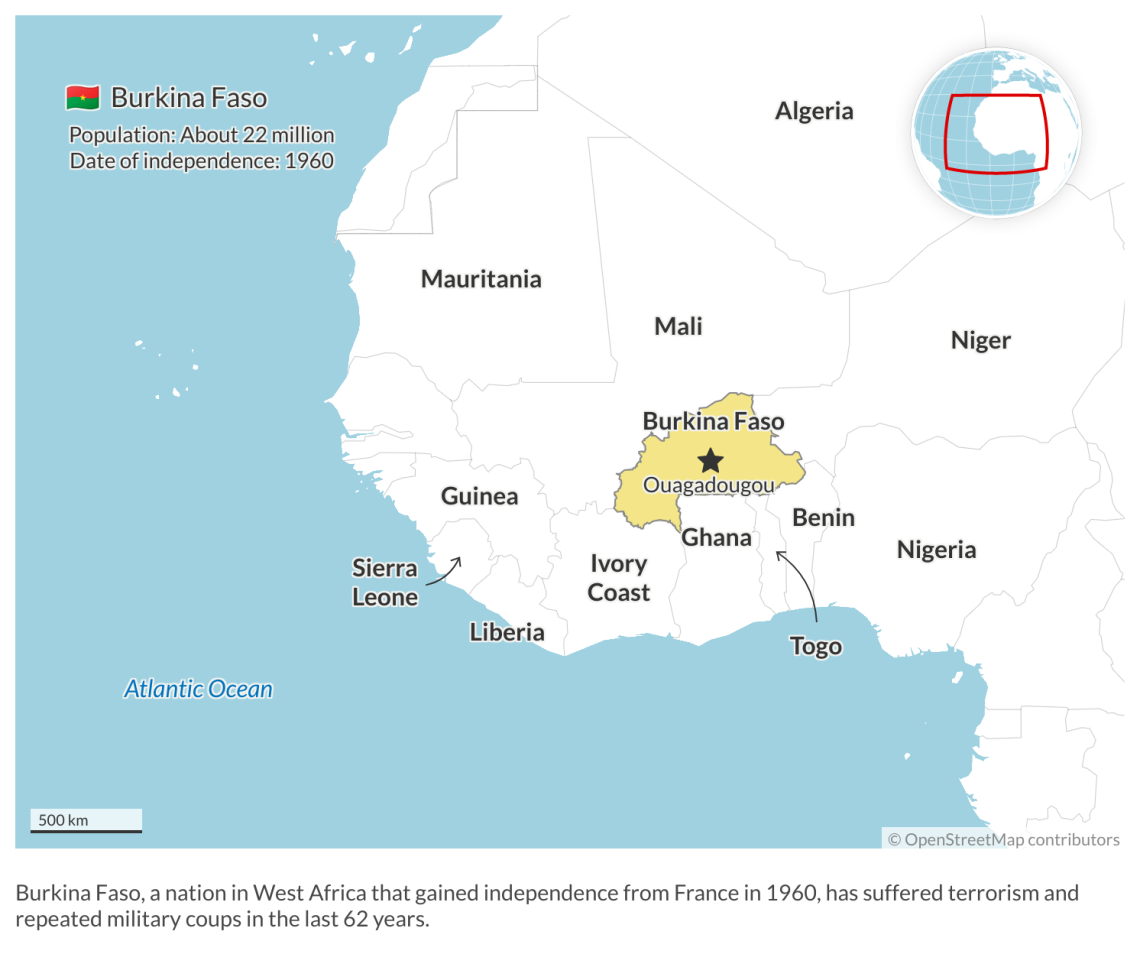

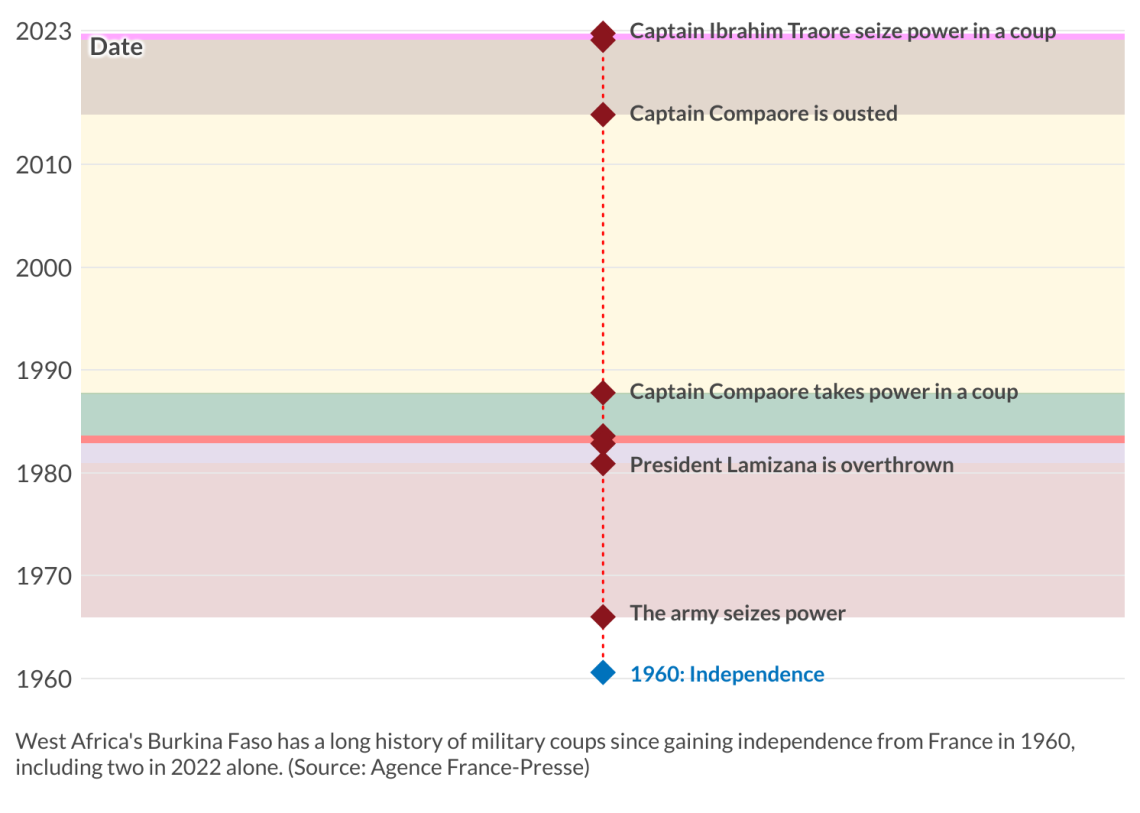

In September 2022, Burkina Faso suffered its second coup in less than nine months. A 34-year-old army captain, Ibrahim Traore, seized power, ousting Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who led a coup in January, toppling former President Roch Marc Christian Kabore. This succession of military takeovers reflects the political instability into which Burkina Faso, the landlocked western African nation of 22 million, has plunged.

As with his predecessor, Mr. Traore justified the takeover on the deteriorating security situation, stemming from a growing jihadist-inspired terrorist threat that has been hitting the country in recent years. Like the January putsch, the trigger was an attack, on September 26, by jihadist forces on a 150-truck convoy loaded with food heading for Djibo, one of the main cities in the war-torn north. The city of 60,000 people has been under siege by terror groups for the past 18 months. The attack, claimed by an al-Qaeda-linked group, killed 37 people, including 27 soldiers. Days later, Mr. Traore seized power in Ouagadougou, the capital that is home to 2.5 million people, with no significant resistance on the streets.

These latest developments reflect two factors key to understanding the situation. The first is frustration with the lack of progress in tackling the terrorist groups and rising violence, for which the former leader, Lieutenant Colonel Damiba, was blamed. One of Mr. Damiba’s priorities had been to improve the country’s security situation, and it was, in fact, the cornerstone of his political mandate. The attack on the convoy was the tipping point highlighting his failure.

As predicted in May, Mr. Damiba had a short window of opportunity to show results to stay in power. With no improvements in the security situation, he lost popular support. The same will be valid for the new leader.

Secondly, divisions within the army persist, and they menace political stability. Mr. Damiba’s ouster highlighted his failure to meet that second critical condition for ruling the country.

Mr. Traore now faces the same challenge.

Read more by Carlota Ahrens Teixeira

Burkina Faso after the coup

Transitional authorities

Maintaining Mr. Traore’s grip on power is likely to have been the focal point in shaping the new ruling configuration. The new military junta retains significant authority while abiding by the 15-nation Economic Community of West African States’ stipulations – those include calling elections by July 2024 with the current transitional leadership ineligible for office. It also has control over the legislature. Between the 16 members of the security-defense forces and 20 other members of parliament selected by Mr. Traore, the new leader is backed by a 36-seat majority. The necessary two-thirds needed to change the transitional charter (47 out of 71 seats) will not prove difficult to find.

Escalating threats and rising insecurity

Jihadist-inspired terrorist groups are wreaking havoc in Burkina Faso’s northern regions, controlling large swathes of territory, especially in the countryside beyond the central government’s reach. According to estimates, the government controls slightly over 50 percent of the country’s territory, and the actual figure could be lower.

Attacks by the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (Jama’ at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin – JNIM), an al-Qaeda offshoot, and by the Islamic State-Sahel are on the rise in the Sahelian tri-border region among Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. By mid-September 2022, more than 3,100 people had been killed – a third more than in all of 2021. Overall, some two million have been displaced.

Mr. Traore has promised to restore security and turn the tide in the fight against the insurgency. However, security remains elusive, with violent events on pace to increase by 35 percent in 2022 compared to early this year.

In late October, apart from the formation of six new rapid intervention units, Mr. Traore announced a nationwide initiative to recruit 50,000 civilians as army auxiliaries to strengthen Burkina Faso’s forces against the jihadists. In 2016, a similar strategy led to the creation of Local Community Security Structures (SCLSs) and, later in 2020, to the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDPs), with an even more militarized role than the SCLSs. These are self-defense militias often operating on their own, unchecked and unsupervised, engaging in extreme violence against civilians with impunity. Killings and massacres have been reported.

Tensions are running high with France, whose colonial rule of the territory extended from 1896 to 1960.

With no guarantee of effective control over thousands of armed civilians, resorting to such measures to improve the security situation could prove counterproductive, potentially exacerbating existing communal tensions.

The attack on the convoy and the control of Djibo reveal another worrying trend. Not only are jihadists expanding their reach, but they are also getting closer to urban centers, isolating important cities and disrupting regional connections. The roads linking Niamey, Niger’s capital, and Ouagadougou, are no longer secure, yet remain the primary connections to and from the countries of the Gulf of Guinea.

The military is fragmented and ill-prepared. The soldiers talk about inadequate kit and assistance. The new government has already sought external support, and a reconfiguration of alliances in the region could be on the horizon.

Facts & figures

Changing alliances

Tensions are running high with France, whose colonial rule of the territory extended from 1896 to 1960. Following the latest coup, hundreds demonstrated in Ouagadougou, demanding the end of the French military presence, strongly contested in West and Sahelian Africa. Mr. Traore’s appointed prime minister, Apollinaire Tambela, has vowed to diversify security partnerships. On its side, France has alluded to the possibility of withdrawing from the country now that Operation Barkhane, an anti-insurgent operation, has officially ended.

The region is increasingly becoming a battlefield in the conflict between Russia and the West. Burkina Faso could be the next stage in the contest.

Moscow is emerging as an increasingly likely partner. Mr. Traore, who is yet to state a clear stance toward Russia publicly, could opt for a stronger alliance with the Kremlin. If not official, such an alliance could happen through Russia’s nominally private military forces, such as the Wagner Group. Mali’s authorities struck such a deal with Russians more than a year ago.

Not only are there signs of a Russian presence in Burkina Faso, but Mr. Traore has traveled to Mali, where he met with his counterpart, Colonel Assimi Goita, to discuss military cooperation. A closer approach to the regime in Bamako could favor closer cooperation with Moscow.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Holding on to power

Mr. Traore’s rule hinges mainly on his ability to deliver greater security. He faces the same challenges Mr. Damiba was confronted with and has little time to prove his worth on the battlefield and as a uniting force within the army. His success is not the most likely scenario.

The military factor

Divisions within the military persist and are a risk to overall political stability. Mr. Damiba was ousted by men who were supposedly loyal to him: Mr. Traore participated in the January coup under Mr. Damiba, as well as several of those who sided with him in October, among them members of Mr. Damiba’s military junta.

However, there are others who continue to side with Mr. Damiba and pose risks to Mr. Traore’s power. Meanwhile, several of the country’s military officers have not participated in either coup, so far remaining on the sidelines.

The fragmented state of the armed forces, the volatility, and the arbitrary means by which power has changed hands suggest that Burkina Faso’s instability is likely to persist. The possibility of other military figures taking center stage remains.

Foreign actors

The balance between the various factions is unclear and foreign actors could easily exploit them. The current situation does not favor direct involvement by France. A likely scenario is for Russia to step in, and Wagner mercenaries seem interested in extending their regional presence. The Wagner Group only acts in countries where Russia has geopolitical interests. Russia’s involvement will become more likely if Burkina Faso becomes increasingly isolated by the international community.

Another possibility is for the new leader to undertake the difficult chore of balancing the support of Russian and Western partners. In either case, the region is increasingly becoming a battlefield in the conflict between Russia and the West, and Burkina Faso could be the next stage in the contest.

Entrenched military rule

Burkina Faso has a long history of military involvement in politics. Neither 2022 coups met popular resistance. In the face of rising insecurity and a discredited political class, people readily turn to the army, believing the solution will come from a military figure. If the security situation does not improve, the less likely it becomes for democratic elections to take place as scheduled and for civilian rule to be restored.

Regional developments could further boost military rule. Conceivably, an alliance of military regimes could be forged among Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Chad.

Security risks and jihadist contagion

Military rule is also likely to deepen Burkina Faso’s isolation from democratic neighbors such as Ivory Coast and Niger, whose help in policing Burkina Faso’s porous borders is essential. The less border control there is, the more permeable Burkina Faso becomes to transnational crime flows and terrorism.

Pressure from jihadist groups, a fragmented military and a protracted institutional crisis, could lead to Burkina Faso collapsing and slowly descending into civil war. That would allow jihadists to come in at full strength, feeding on the country’s instability. The more Burkina Faso turns into a gateway to West Africa, the higher the risk of regionalization of violence coming from the central Sahel region.