In Cameroon, centralization leads to strife

Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis is flaring up as resentment over years of centralization bubbles to the surface.

In a nutshell

- Centralized rule has radicalized Cameroon’s Anglophone minority

- Political actors have replaced civil society in areas where devolution has failed

- Internal strife is weakening the country’s postcolonial model of stable authoritarianism

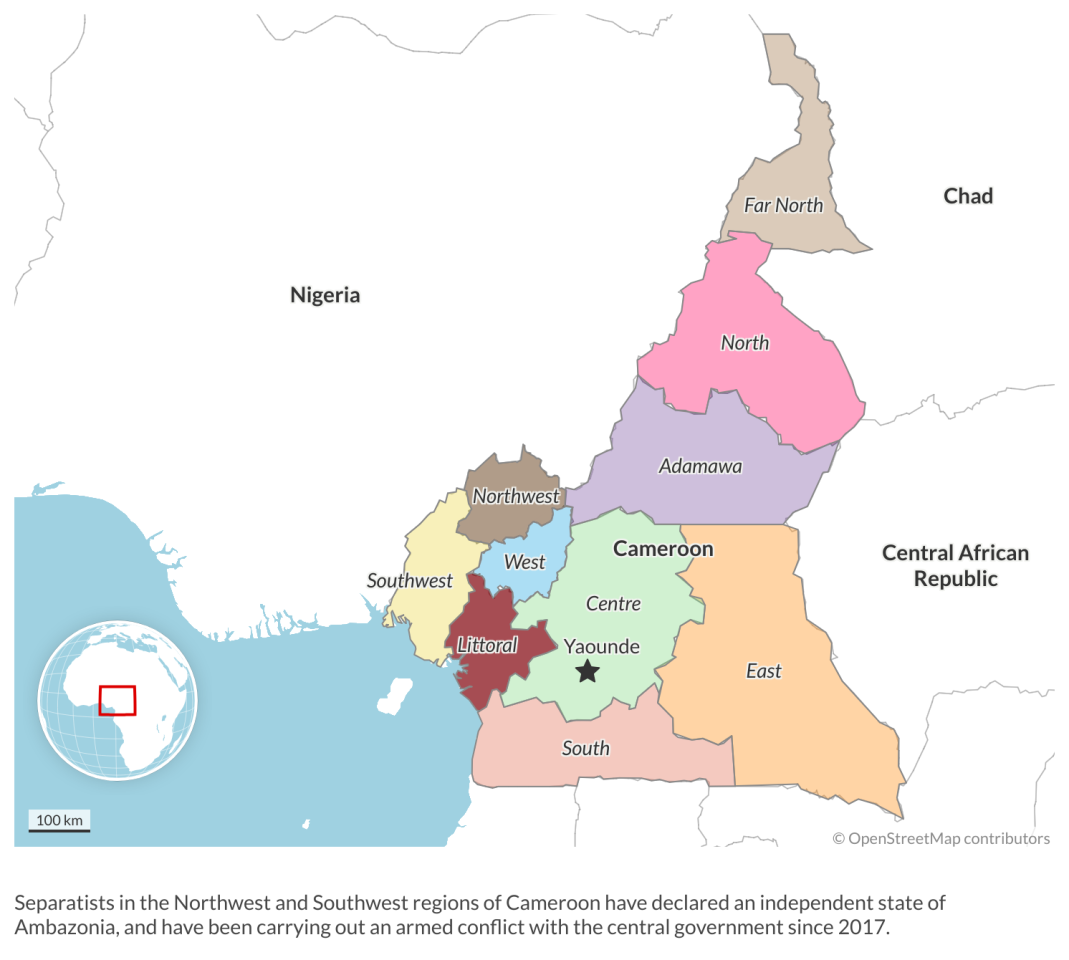

Since 2016, the conflict in Cameroon between armed separatists and government forces has killed more than 6,000 people and displaced over 500,000 in the country’s northwestern and southwestern regions, where 2.2 million people need humanitarian assistance. The government’s hybrid approach to the crisis, combining political and security measures, has failed to appease local aspirations for autonomy, federalism, or even secession.

Compounding the problem, Cameroon – which has long been a stable authoritarian regime – looks poised to enter a process of leadership change that will make it more challenging to find a negotiated solution for the conflict.

Breakdown of federalism

English-speaking Cameroonians make up approximately 20 percent of the country’s population. To understand the causes of the conflict with the predominantly Anglophone population of the country’s Northwest and Southwest, one must examine both remote and immediate causes.

The crisis, like most similar clashes across the continent, is a product of the artificial borders drawn by colonial powers, along with the failures of decolonization and post-independence state-building. In Cameroon, as elsewhere, these failures were exposed by ethnic, tribal, and cultural cleavages that fueled resistance to a centralized state – making ethnicity a root cause and accelerator of political conflict.

The situation became clear in the 2018 presidential campaign, when incumbent President Paul Biya defeated Maurice Kamto in a free but not fair election. The ballot’s aftermath exposed the ethnic dimension of tensions between the Bamileke and Bamoun, who inhabit western Cameroon, and the Bassa, perceived by many as the country’s hegemonic ethnic group, buttressed by a centralized political structure viewed by much of the populace as illegitimate.

Facts & figures

In the 19th century, present-day Cameroon was a German protectorate. After World War I, it was divided by a League of Nations mandate into two unequal parts – British Cameroon and French Cameroon – under the administration of those two colonial powers.

By the late 1950s, as decolonization in Africa accelerated, the newly independent states tried to use these inherited administrative structures to forge national identities in a continent fragmented along multiple ethnic, religious and geographic divides, and constrained by the arbitrary colonial-era borders.

French Cameroon gained independence in 1960, becoming the Republic of Cameroon. Inhabitants of the Trustee Territory of Southern Cameroon were given a choice: they could join recently independent Nigeria as a federated state or combine with the Republic of Cameroon, also as a federation. In a United Nations plebiscite organized in 1961, the latter option was chosen, transferring sovereignty to the Federal Republic of Cameroon. Many in the Anglophone states, however, accused French Cameroon of ignoring the principles of federalism, instead maintaining the centralized practices set forth by the unitary Constitution of 1960.

Escalating crisis

Federalism was formally overturned in 1972, under President Ahmadou Ahidjo, who changed the name of the country to the United Republic of Cameroon. In 1984, President Biya went one step further and truncated the official designation to the Republic of Cameroon, reverting to the original term under French administration. Anglophones reacted by challenging the decision in the courts.

Resentment and grievances generated by the failure of the federal principle resurfaced in 2016, triggered by the imposition of French as the language of education, the courts and administration. Since the Constitution grants equal status to the English and French languages, Anglophones perceived the imposition of French-speaking teachers, lawyers and judges as a form of marginalization. Initially, discontent came in the form of peaceful protests and strikes, with calls for the restoration of federalism.

More on Africa

To empower Africa, look to ethnic leadership and subsidiarity

Africa and foreign influence

The turning point in the crisis, starting its inexorable escalation into an armed conflict, came in January 2017, when the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium, an umbrella of civil society organizations, started to organize a stay-at-home boycott campaign called Operation Ghost Town Resistance. In October, secessionist groups declared the independence of the Federal Republic of Ambazonia in Cameroon’s Northwest and Southwest regions. The declaration stated that Anglophone Cameroon had been recolonized rather than decolonized and was a case of black-on-black colonization.

The declaration started a shift in which civil society actors were replaced by political actors, demands for autonomy were dropped in favor of independence, and armed struggle became a viable option. The Ambazonia Defense Forces, as the armed wing of the separatist movement called itself, took control of portions of the territory. President Biya deployed the army in the Anglophone regions, promising to crush the rebellion.

Hybrid approach

To overcome the crisis, the Cameroonian regime has resorted to a mixture of political and security measures. The strategy is to appease groups demanding more autonomy, while militarily defeating the separatists.

After the 2017 strikes, the government established a National Commission to promote bilingualism and multiculturalism. In 2019, President Biya launched a national dialogue on unity and peace. More importantly, at least from a formal standpoint, in 2019 the parliament granted the Northwest and Southwest special status. Based on “their linguistic particularity and historic heritage,” these areas were given more autonomy to run local affairs, while receiving funds earmarked from the central government for local and regional governments.

In theory, the devolution of more power, responsibility and resources to regional bodies could be a remedy for the crisis. In practice, however, the decentralizing initiative failed. Firstly, the central government did not follow through on its 2019 promise to provide the funds and autonomy for real local government. Spending decisions still depended on approval from the capital, while centralization continued to rule even mundane aspects of people’s lives (for example, students completing their degrees claim they are forced to travel to Yaounde to get an official certificate).

Secondly, a political radicalization had taken place, as many Anglophones internalized secessionist denunciations of Yaounde’s “annexationist” impulses and came to believe that autonomy was no longer enough, leaving formalized federalism or independence as the solution.

The Cameroonian regime also took hard measures to address the crisis. In 2017, the government imposed a 90-day internet ban on the Anglophone region, which bruised an already fragile economy and inflamed feelings of marginalization. The government also deployed the Rapid Intervention Battalion – an elite internal security unit of the Cameroonian army that reports directly to the president – to fight the separatist forces.

Crisis accelerators

A convergence of factors suggests that finding a negotiated, sustainable solution to the current crisis may be difficult.

The first is that Cameroon’s Anglophone regions are endowed with significant natural resources, including timber, oil and fertile land. While the competing political claims for autonomy and independence are historically rooted, the competition for resources often acts as a grievance “accelerator,” as can be seen in other separatist regions in Africa where economic self-determination is salient.

A second factor is the political and regional divisions within the Anglophone regions themselves. While in 2016 various groups united behind the goal of defending their common Anglophone identity against the central state, differences regarding the means and ultimate ends are now evident. While some would accept the autonomy granted under special status, others want a return to the two-state federation and a third group insists on the armed struggle to win independence. Moreover, there are now multiple separatist militias operating in the region, feeding an escalating spiral of violence against civilians by both militias and security forces.

A third factor is the regional context. The security outlook in West Africa has deteriorated over the past decade, amid a vicious cycle of terrorism, organized crime, food insecurity and displacement. In Cameroon and Nigeria, terrorist groups are active in the northern regions, while separatist militias operate in areas immediately to the south. Some have begun to cooperate among themselves, as seen by the 2021 alliance between the Ambazonia Defense Forces and the armed wing of the Indigenous People of Biafra, a Nigerian-based separatist movement.

Finally, social media are playing a growing role in the conflict, as parties turn to the digital sphere to air their grievances and spread information or disinformation. Digital platforms are particularly important for the interaction they allow with diaspora communities, which are key sources of intellectual and financial support. However, social media should be treated as a vehicle or medium, rather than as a root cause of conflict.

The end of stable authoritarianism

The Anglophone crisis must also be analyzed in the context of Cameroon’s political system, which is a case study of stable authoritarianism. Since winning independence more than six decades ago, the country has only had two presidents. President Biya, who came to power in 1982, is Africa’s longest-tenured leader after Teodoro Obiang, who has ruled Equatorial Guinea since 1979.

As in other African countries, Cameroon’s authoritarianism survived the so-called third wave of democratization, which took place in the 1990s. While the country formally adopted multipartyism, the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) retained its hegemony and Mr. Biya has continued to win every presidential ballot since he came to power.

Not surprisingly, the consolidation of personalized and resilient authoritarianism went hand in hand with centralization. In 1982, as mentioned, the president used his power to establish a unitary and more centralized state. At the epicenter of power was the presidency, where President Biya exercised the direct power of appointment for all senior posts. Presidential term limits were removed from the Constitution in 2008, a year marked by violent protests over high food and fuel prices, which Mr. Biya seized upon as a pretext to stay in power indefinitely. A clause granting regions the power to elect governors was also deleted from the country’s constitution.

Even had President Biya behaved more moderately, the very nature of Cameroon’s regime – especially its dependence on dense patronage networks – was not conducive to decentralization, let alone federalism. Decision-making powers and funds have been tightly concentrated in national governing bodies, to the detriment of regional and municipal governments.

Scenarios

The Anglophone crisis is a cautionary tale about the centralized state model that has prevailed across Africa since independence. That model often ignores the importance of ethnic, cultural and religious identities. When these identities are perceived as being threatened – in Cameroon’s case, through fears of cultural marginalization in the educational, judicial and administrative systems – they generate local resentment of central authority and autonomic or separatist claims, which in the Anglophone regions are based on historically rooted notions of a common identity and territory.

Moreover, Cameroon’s regional crisis of legitimacy is now being reproduced at the national level. President Biya is 90 years old. Whether or not he runs for another term in 2025, succession is clearly an inevitable question. This outlook makes it more challenging to find a negotiated and peaceful solution to the Anglophone crisis. Periods of leadership transition (and the struggles they trigger) under resilient and personalized authoritarian regimes are often unpredictable. Given the several failed attempts at international mediation, and in light of widespread Anglophone skepticism about the government’s commitment to decentralization, the conflict seems bound to continue.