Simmering tensions in Central Africa

Security instability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo could soon spark a regional war.

In a nutshell

- Rebel groups and national armed forces are clashing in the DRC

- Neighboring states are fighting proxy wars in the area

- Violence could escalate into a full-fledged armed conflict

At the end of August, suspected rebels killed at least 14 people in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The country’s army blamed it on the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan militia that has operated in the DRC for the better part of three decades.

For the past 25 years, the resource-rich Eastern DRC has been ungovernable, gradually becoming an arena of competition between states racked by intermittent proxy wars and an operating base for multiple rebel groups.

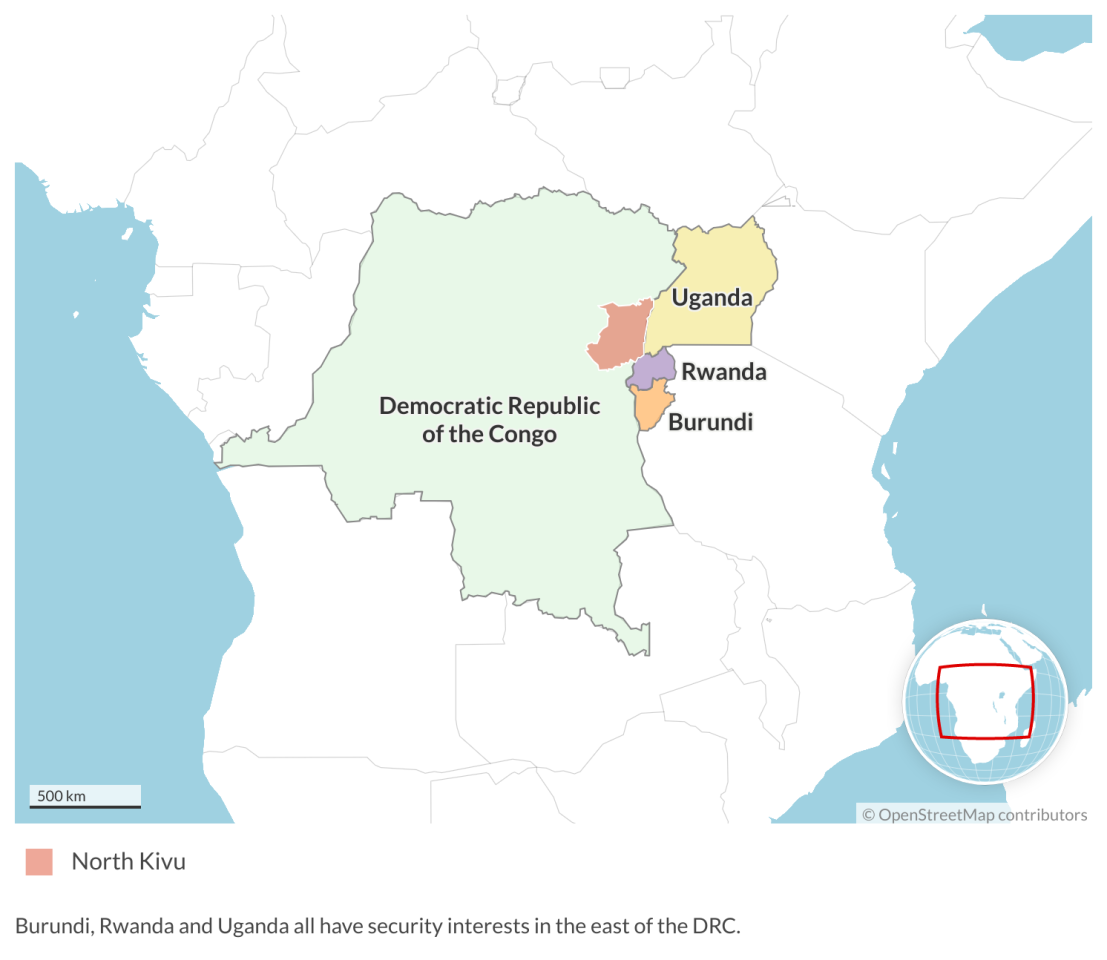

The current crisis started in November 2021, when the rebel military group known as M23 attacked the Congolese Armed Forces in North Kivu. The attacks occurred at a moment when the DRC and Uganda were intensifying both their economic and security cooperation. The M23 offensive reignited a dormant regional crisis whose root causes were never addressed.

Origins

Those roots go back to 1994. The genocide in Rwanda triggered an exodus of two million refugees into neighboring countries, most of them to Zaire (now the DRC). Rwanda and Uganda would then play a key role in ousting President Mobutu Sese Seko in 1996 by supporting Laurent Kabila during the First Congo War.

Why did the M23 come back, almost a decade after being neutralized?

As a result, armed groups like the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) or, later, the March 23 Movement (M23) were created and became agents of proxy wars in the region.

The FDLR was founded in Congo in 2000 by former members of the Rwandan genocidal regime. While operating in the DRC, its main goal is to defeat the current Rwandan rulers, and the movement is seen by Kigali as an existential threat.

The M23 was founded in 2012 by Congolese Tutsis with the support of Rwanda and Uganda. Its declared purpose is to protect the Tutsi populations in Eastern Congo. Its name derives from the peace agreement signed on March 23, 2009, between the Congolese government and the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP). In 2012, former CNDP members accused the government of not keeping its side of the deal and, in a quick offensive, took control of the city of Goma. M23 was defeated in 2013 in what was perceived as a diplomatic and military success. The decision by the United States and the European Union to suspend or redirect international aid to Rwanda was particularly effective, and the leader of the M23, Jean Bosco Ntaganda, eventually turned himself in at the U.S. embassy in Kigali.

Why now?

Why did the M23 come back, almost a decade after being neutralized? First, because the demobilization and disarmament processes failed, despite all the mediation efforts. Second, these movements are used by regional powers to wage proxy wars in the struggle to secure influence and access to key resources.

The return of the M23 is a consequence of the diplomatic, economic, and military rapprochement between the DRC and Uganda, which intensified tensions between Uganda and Rwanda. Relations between the two countries deteriorated in 2019, when President Paul Kagame accused the Ugandan regime of supporting members of the Rwandan opposition. The border between the two countries at Gatuna was closed for almost three years, disrupting key trade routes.

Tensions between Rwanda and the DRC are rooted in a myriad of cross-border political, security and economic interests.

Like Rwanda, Uganda also has a strong security motive to increase its presence in the DRC. The Islamist rebel group ADF has operational bases in North Kivu and Ituri, and carried out bomb attacks in Kampala in November 2021. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, who has been in power since 1986 and is in an increasingly fragile position, has negotiated a memorandum of understanding with DRC President Felix Tshisekedi to construct a 223-kilometer road network connecting Eastern Congo to Uganda. The agreement also includes the deployment of Ugandan forces in Congolese territory, which triggered anxiety in Rwanda.

Burundi also has vital security interests in the DRC. President Tshisekedi has recently allowed Burundian forces into Congolese territory to neutralize RED-Tabara, a rebel group opposed to the Burundian government and responsible for attacks in Burundi.

David and Goliath

In a recent speech, President Kagame likened Rwanda and the DRC to David and Goliath. By area, Rwanda is one of the smallest countries in sub-Saharan Africa, while the DRC is the largest. Moreover, the DRC’s population is about 90 million, while Rwanda’s is only about 13 million.The Congolese armed forces are more than four times bigger than the Rwanda Defense Force and, unlike Rwanda, the DRC is endowed with abundant natural resources. However, Rwanda is a much more functional state and has more international sway.

Tensions between Rwanda and the DRC are rooted in a myriad of cross-border political, security and economic interests. The Rwandan regime believes it is responsible for the protection of all Tutsis, even outside Rwanda. Moreover, the existence of an external enemy represents an opportunity for the regime to reinforce internal cohesion.

Eastern Congo is seen by Uganda and Rwanda as an extension of their own territories. Through rebel groups or state-sponsored military presence, these regimes try to increase their regional leverage, pursue political goals, and secure access and control over supply chains and natural resources.

Facts & figures

Failed mediation and regional shifts

The Great Lakes Region has highlighted the United Nations’ limits as a peacekeeper. After failing to prevent the genocide in 1994 – and despite the presence of MONUSCO, a 16,000-strong peacekeeping mission – successive UN efforts in the region have failed. One factor is the uneasy relationship between the UN and the Rwandan regime, aggravated by a series of UN reports accusing the RPF of committing crimes against humanity and denouncing Rwanda’s support of the M23. However, the UN is also discredited in the DRC, where it faces accusations of sexual abuse and trafficking. In July, at least 30 people died in Goma in violent protests against the presence of MONUSCO. The mission’s spokesperson has been expelled by the Congolese authorities and, in Butembo, the UN base had to be evacuated and troops redeployed outside the city.

The region will likely remain a mosaic of rebel groups, sustained by long-standing identity divides that defy state borders.

Unlike the UN, the U.S. has cultivated good relations with Rwanda. This is not only an acknowledgment of its failure in 1994, but also because Rwanda was seen by Washington as a reliable partner, an agent of stabilization in the region and a rare aid success story. However, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently visited the country and delivered a speech where he mentioned “credible” reports indicating that Rwanda is destabilizing the region by continuing to support the M23. As the U.S. tries to increase its presence in the DRC and relations with President Tshisekedi improve, Washington’s goodwill toward Kigali may diminish.

At the regional level, the management of the DRC crisis is shifting from south to east. The African Union has appointed Angola as chair of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region to mediate. In July, both countries adopted the Luanda Roadmap de-escalation measures. However, as the DRC recently joined the East African Community (EAC), the process is unfolding in parallel and with more ambitious goals, including dialogue between the Congolese government and rebel groups and the deployment of a regional force to “contain, defeat and eradicate negative forces” in Eastern Congo. In August, a Burundian contingent was deployed under the EAC mandate. Contingents from Kenya, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda are expected to join the force.

Scenarios

Three main scenarios must be considered. The first one is that Eastern Congo will remain an ungovernable territory where rebel groups establish their operational bases while competing or cooperating with various political and military actors. A second scenario could see proxy wars replaced by an armed conflict between Rwanda and the DRC. Finally, a third possible scenario is a successful demobilization process, followed by stabilization and peace.

The evolution of the situation will depend on domestic politics as well as international actors. But considering the events of the last two decades, as well as current trends, the most likely scenario is the first one.

Security concerns and economic interests will continue to push Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi into Congolese territory. The region’s economic relevance is set to increase as the world intensifies its consumption of cell phones and shifts to electric mobility (60 percent of the world’s coltan reserves are located in the Kivu province, while more than 70 percent of the world’s cobalt lies in the DRC, mostly in Kivu). The region will likely remain a mosaic of rebel groups, sustained by long-standing identity divides that defy state borders. Islamic terrorism is also likely to increase.

The EAC initiative may contribute to avoid another “African world war,” as the force is anchored in the interests of the states involved: Uganda wants to neutralize the ADF, Burundi the RED-Tabara and South Sudan the Lord’s Resistance Army. However, by excluding Rwanda, the initiative may be doomed to fail. Moreover, it is not clear who will provide the funding for this joint force, expected to assemble between 6,500 and 12,000 troops.

The evolution of the political situation in the DRC, Rwanda and Uganda will also affect the current crisis. In the DRC, the 2023 presidential election may provide an opportunity for former President Joseph Kabila to come back and replace President Tshisekedi. Candidates may be tempted to foster anti-Rwandan feelings in some regions, thus leading to further violence.

In Uganda, Mr. Museveni will likely exit power by 2026, which may contribute to a rapprochement between Kigali and Kampala.

In Rwanda, President Kagame has announced his intention to run again in 2024, and he is expected to achieve another landslide victory. With the internal opposition silenced or coopted, his main risk lies in the armed opposition outside the country, and in potential cracks within the army. Considering this, it will be vital for Mr. Kagame to secure a position within the DRC through the M23 or other insurgent movements – even if this means an end to U.S. aid.