Central Asia is coming into its own

Russia’s war in Ukraine has alienated Central Asian nations once part of the Soviet Union. They may look for new patrons or, at last, seek their own way

In a nutshell

- Economic entanglements are harder to break than security ones

- Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan could become a regional powerhouse

- Turkey, not China, may best capitalize on Moscow’s fading role

At the outset of 2022, Kazakhstan was shaken by a wave of social unrest. Innocuous at first, it rapidly escalated from anger over fuel price hikes to broader political discontent. At the invitation of President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Russia sent troops to help restore order. The operation was successful. After less than two weeks, foreign troops were withdrawn, and all seemed content with the outcome.

At the outset of 2023, the stage had been completely transformed. Because of its brutal war against Ukraine, Russia has witnessed former friends and allies distancing themselves from the Kremlin. The significance of this trend was especially pronounced in Kazakhstan.

The importance of Kazakhstan

Ever since the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union, the Central Asian nation of 19 million people had been the Kremlin’s most trusted friend and ally. That is no longer the case. President Tokayev has made it clear that while he will not join Western sanctions against Russia, he has no intention of supporting any form of the Russian annexation of any Ukrainian territory. His attitude toward the Kremlin has broad support among Kazakhs.

Russian President Vladimir Putin made five trips to Central Asia in 2022, seeking to shore up the role of Russia as a regional hegemon. But his travels have mainly illustrated just how fragile that position has become. At a Caspian Summit meeting in Turkmenistan in early July, he was humiliated as the only foreign dignitary not to be received at the airport with the customary greeting of bread and salt. And photo ops have shown other leaders reluctant to stand next to him.

Leadership in Central Asia

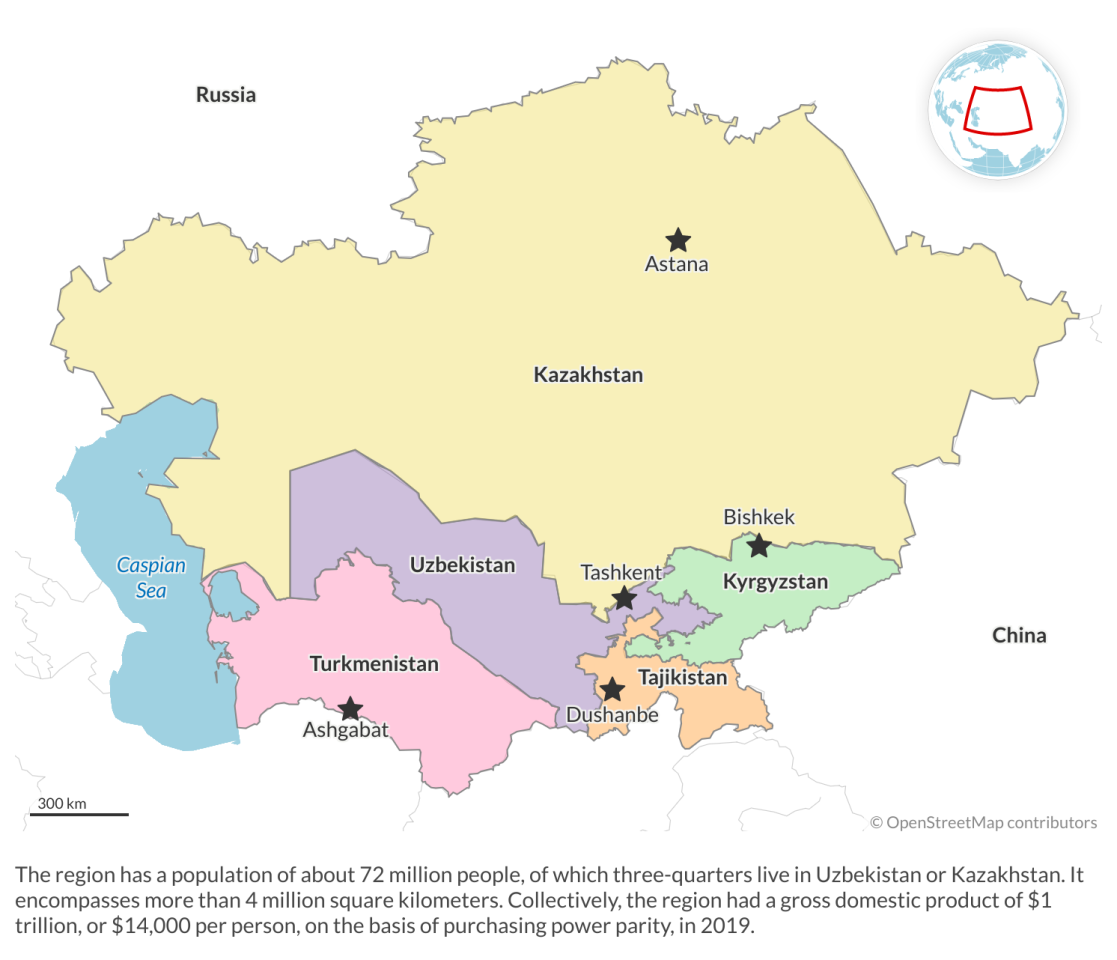

The implication is that no foreign nation has a dominant leadership role in Central Asia, home to 72 million people among the five ex-Soviet republics. The main questions are whether Russia will claw back its position as the leading security provider and whether China will emerge from its current Covid-19 mess as the most important economic player in the region. The alternative options are that Central Asian governments will find new external patrons or finally rise to the challenge of becoming masters in their own houses.

Russia is currently failing, primarily as a provider of security, but also as a leader in economic integration. The armed intervention in Kazakhstan was conducted under the aegis of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) created in May 1992. Patterned on NATO, it was designed to ensure that Russia would remain the leading power in post-Soviet space, much as the United States dominates NATO.

At its peak, the CSTO included nine of the 15 former Soviet republics. Following the departures of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Uzbekistan, only six remain. One is Armenia, which has long been on the Russian side, with a significant Russian military base on its territory. When it was attacked by Azerbaijan in the fall of 2020, Armenia sought support from the CSTO, but that appeal was denied. Armenian forces were routed from Nagorno-Karabakh.

Central Asia is becoming an open area for the emerging energy and security axis between Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Two others are Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Aside from their marginal importance, they also have severe bilateral disagreements. Last September saw an eruption of border clashes that left close to 100 dead and many wounded. The government in Kyrgyzstan called the crisis an attempted invasion by Tajikistan.

That leaves Russia with Belarus and Kazakhstan as its only reliable allies. If it is defeated in Ukraine, Moscow may face a collapse of the regime in Minsk, meaning that the CSTO will effectively be reduced to an alliance between Russia and Kazakhstan. This scenario makes the cold shoulder from President Tokayev so important.

In a bizarre connection with Russian military failures in Ukraine, the rhetoric against Kazakhstan has also become increasingly aggressive. Comparisons between the Russian-speaking Donbas in Ukraine and the Russian-populated north of Kazakhstan have long been made. But Russian warlords have escalated to open threats of an armed invasion. In response, Kazakhstan has moved its troops to the Russian border.

Facts & figures

CSTO will fade into irrelevance

The CSTO will not be disbanded – large organizations of this kind tend to live forever – but will fade into irrelevance. It was highly significant that a CSTO meeting in Armenia in November concluded with the host, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, refusing to sign the final declaration.

While military cooperation may be terminated on short notice, the demise of economic cooperation is a slower game. That will make it possible for Russia to keep up a facade of remaining an important player in economic integration.

Much as the CSTO was patterned on NATO, the Kremlin’s parallel project for economic integration was patterned on the European Union. It began with a Customs Union that morphed into a Common Economic Space, culminating in 2015 in the Eurasian Economic Union.

The founding members again were Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus, now together with Kyrgyzstan. Although Armenia subsequently joined, Yerevan’s entry does not make much difference. If Kazakhstan leaves, it will be the end of the story.

Booming trade statistics are misleading

At a casual glance, it might seem that Russia’s economic relations with Central Asia are booming rather than fading. Official statistics show that trade has increased substantially during the war in Ukraine. While the Kremlin is touting this as a sign that Russia is not isolated, it deserves to be taken with a very large pinch of salt.

One driver of the boom is trade diversion caused by Western sanctions. While this is beneficial for regional economies, it means that Russia is developing trade with Central Asia as a replacement for doing business with the advanced economies of the West. The longer-term consequences of this shift will be highly damaging. Another driver is sanctions-busting, meaning that Russia is paying top dollar to get access to vital electronics. The rapid growth in Russian imports of pumps for breast milk is hard to explain in any other way than as a roundabout way to get critically needed microchips.

Soviet-era elite networks are disappearing

Another critical factor that may keep trade flowing is that relations between Russia and Central Asia remain dominated by Soviet-era elite networks. But that will also fade. As the younger generation takes over, links to Russia will be replaced by nationalist sentiments.

The likelihood that China will be able to capitalize significantly on the fading role of Russia is slim.

A third factor that may indicate growing ties is that many of the hundreds of thousands of young Russians escaping mobilization are highly educated and bring skills that may trigger a boom in the Kazakh information technology industry. This migration is welcome because many men will bring their families with them and integrate into society. The development will be a major net gain for Kazakhstan and a severe loss for Russia.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan: a new regional powerhouse?

An important indicator of how Kazakhstan is turning its back on Russia lies in its growing rapprochement with Uzbekistan. At a meeting in Tashkent just before Christmas of 2022, the two sides not only signed a host of agreements on economic cooperation. They also agreed on border demarcation, setting aside prior differences. These steps may have important longer-term implications, creating a regional powerhouse. While Kazakhstan has the largest economy in the region, Uzbekistan has the largest standing army and is the most populous with 35 million people. Given that both are major energy producers, they will form an attractive partner for outside players.

China squanders opportunities in Central Asia

The likelihood that China will be able to capitalize significantly on the fading role of Russia is slim. The early phase in the rollout of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was associated with massive Chinese investment in regional infrastructure. But in recent years, the BRI has been sputtering, leaving in its wake growing anti-Chinese sentiment. As regional feelings toward Russia also turn negative, President Xi Jinping will not be helped by his proclamation of an “unlimited friendship” with President Putin. And the boom in Covid infections and deaths that was triggered by the sudden removal of restrictions in China is bound to cause disruptions in economic activity.

Negative sentiments toward Russia will also affect another emerging axis – between Russia and Iran. The decision by Tehran to supply drones for the Russian military has not been well received anywhere else. Suppose Iran moves to escalate by providing Russia with its long-range ballistic missiles. In that case, it may be rewarded with Russian support for its nuclear program and sales of advanced Russian military aircraft. But the price for such support will be paid in creating an open door for Turkey to promote its pan-Turkic agenda in Central Asia.

Azerbaijan’s recapture of Nagorno-Karabakh has opened a transport corridor for Turkey that allows it to bypass and essentially isolate Iran from Central Asia. Ankara may also count on the fact that Azerbaijan has a strongly negative attitude to its southern neighbor, to the point even of allegedly having offered Israel support in the event of air strikes against Iran.

Scenarios

Central Asia is becoming an open area for the emerging energy and security axis between Turkey and Azerbaijan. In the short term, it will be about exploiting political openings from the combined weaknesses of Russia and China. In the longer term, the real prize concerns investments in security and energy.

In one scenario, Turkey and Azerbaijan will succeed in building a firm security presence in the region. While the war in Ukraine has been a disaster for Russian arms producers, it has boosted the standing of Turkey, enhancing the likelihood that Ankara may score serious deals with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. On a parallel track, it may also succeed in promoting investment in infrastructure to route energy flows from Azerbaijan to Turkey and onward to Europe. If the Russian Federation begins breaking up, Kazakhstan may even succeed in shaping links with Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, causing “Russian” oil to be routed south instead of west and east.

The other scenario sees Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan develop a more independent posture, balancing Turkey against Russia and China. The problem for Uzbekistan is that it placed a big wager on the Taliban being ready to protect infrastructure investment via Afghanistan toward India and Pakistan. That wager may now be turning sour. Both countries have also invested heavily in being part of the Trans-Caspian transport corridor, the success of which depends on maintaining a significant flow of goods from China. And any ambition to create a more independent powerhouse in the region will have to overcome numerous intraregional tensions. All this points to an advantage for Turkey.

Irrespective of how far Ankara will succeed in pushing its nationalistic agenda of pan-Turkism in Central Asia, both scenarios suggest that energy flows from the region will increasingly be routed through Azerbaijan and Turkey. That would allow Ankara to slide into the position of a new energy hub. And the poor showing of Russian arms in Ukraine will create substantial market opportunities for Turkish manufacturers.

Since Turkey remains a member of NATO, the implication is that because of its brutal aggression against Ukraine, the Kremlin has boosted NATO expansion into what it has long viewed as its own backyard.