Central Asia deals with the Taliban

Many fear chaos will return to Afghanistan once NATO troops leave the country. Several countries in Central Asia could significantly boost their economies by collaborating with Kabul and the Taliban – if the security situation allows a partnership to develop.

In a nutshell

- Security concerns over a post-NATO Afghanistan are on the rise

- Central Asia fears a Taliban regime would threaten stability

- Several states in the region have a lot to gain by collaborating

The pending withdrawal of NATO troops from Afghanistan has reignited old fears over what will happen when the country is left to fend for itself. Not all foreign troops will be withdrawn by May of this year, as agreed by the Taliban and the United States in Doha in February 2020. Still, U.S. troops are now due to leave by September, and some regional powers have been making plans for a post-NATO era.

Foreign troop withdrawal could well mean a return to power for the Taliban, and thus a resurgence of the violence that characterized their rule. The movement could also ally with other Islamist groups like al-Qaeda, Islamic State and Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Yet, there is also a possibility that the change will bring a new dawn for the region. All parties concerned stand to gain substantially from peace and cooperation. Major infrastructure projects that have long been in the making could finally be developed. Pipelines and rail links across Afghanistan could provide access to new markets and port facilities on the Indian Ocean. Fresh water could be pumped from the mountains in central Afghanistan into the arid plains of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. And high-voltage power lines could enable the transmission of surplus hydroelectricity from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Central Asian states that border Afghanistan have separate security strategies, making a regional front unlikely.

This scenario would bring a much-needed economic boost to the battered economies in the region, and lower tensions between major powers would reduce the long-standing risk of a regional war erupting. Whether this is a realistic outcome hinges on three questions.

- First, will the Taliban be sufficiently motivated by economic gain to keep their security guarantees? Since they broke many past promises, there are concerns over whether they will stick to their word this time.

- Second, will regional powers place enough trust in the Taliban to get involved? Given the problematic nature of the alternative, the outlook on this count is more promising.

- Third and most importantly, will outside investors commit to large projects in the area? Building infrastructure would require not only funding but also sending construction workers to areas where they risk being kidnapped or killed.

Ultimately, what is to come depends on whether economic rationality will finally prompt Islamist radicals to mend their ways and cooperate with constructive governance.

Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbors

Ever since Russia withdrew from its own 10-year Afghan quagmire, it has worried about an Afghan invasion into Central Asia. Moscow was happy to have NATO provide security, and it remains deeply concerned about what a post-NATO reality might look like. The Central Asian states that border Afghanistan have good reason to share these fears. They have long been building up their own defenses. The three countries have separate security strategies, making a regional front unlikely.

Tajikistan has a 1,300 kilometer-long border that winds through rugged, mountainous terrain – a major route for drugs from Afghanistan. Senior officers from the Russian military base in Dushanbe have been implicated in trafficking activities. China has provided support building border controls and is even claimed to have built a military base of its own. In addition to security motivations, Beijing has plenty of incentive to support major infrastructure development. Improved links to the south would add substantial value to the rollout of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Facts & figures

Uzbekistan has only a 144 kilometer-border that runs along the Amu Darya river. With Islamist insurgents on its own territory, Tashkent has invested heavily in securing the area. It is patrolled by heavily armed soldiers, with a solid barrier of two barbed wire fences, one of which is electrified at 380 volts, and land mines.

Despite security concerns, Uzbek officials are now discussing Afghanistan as a potential safe transit zone, providing access to Pakistani seaports on the Indian Ocean. On the Uzbek side of the border, a road and a railway line connect with Afghanistan at a major crossing point just east of Termez. A southbound rail link to Mazar-i-Sharif and Kabul could proceed to Torkham, on the Pakistani border.

Security is not the only reason why the Turkmen government may be keen on a deal with the Taliban.

In this puzzle, Turkmenistan is an enigma. A hermetically sealed country with a strict tradition of nonalignment, it holds the key to a sustainable deal with the Taliban. Its 800 kilometer-border runs across sparsely populated deserts and low hills. There are two crossings, one a dirt road. The nature of the terrain means that the costs of rolling out major infrastructure would be modest.

Although the authoritarian nature of the regime makes it difficult to ascertain what is going on in Ashgabat, there have been signs of increasing concern over border security. Unconfirmed reports in early 2020 suggested that Russian troops have begun operating along the border. Other sources claim that all males below 50 have been vetted for service in the army reserve. But security is not the only reason why the Turkmen government may be keen on a deal with the Taliban.

Scenarios

Turkmenistan

Like Afghanistan, Turkmenistan is an economic basket case. Given that the country sits on the world’s fourth-largest reserves of natural gas, it could have been a true success story, competing with other major exporters like Kuwait, Algeria and Norway. Decades of abysmal governance have failed to transform its assets into wealth. Under the current conditions of depressed energy demand, resources in the ground have limited value.

The sharp fall in earnings from natural gas exports has sent the already wobbly economy into a tailspin. A decision to radically curtail food imports has brought back Soviet-era scenes of empty store shelves.

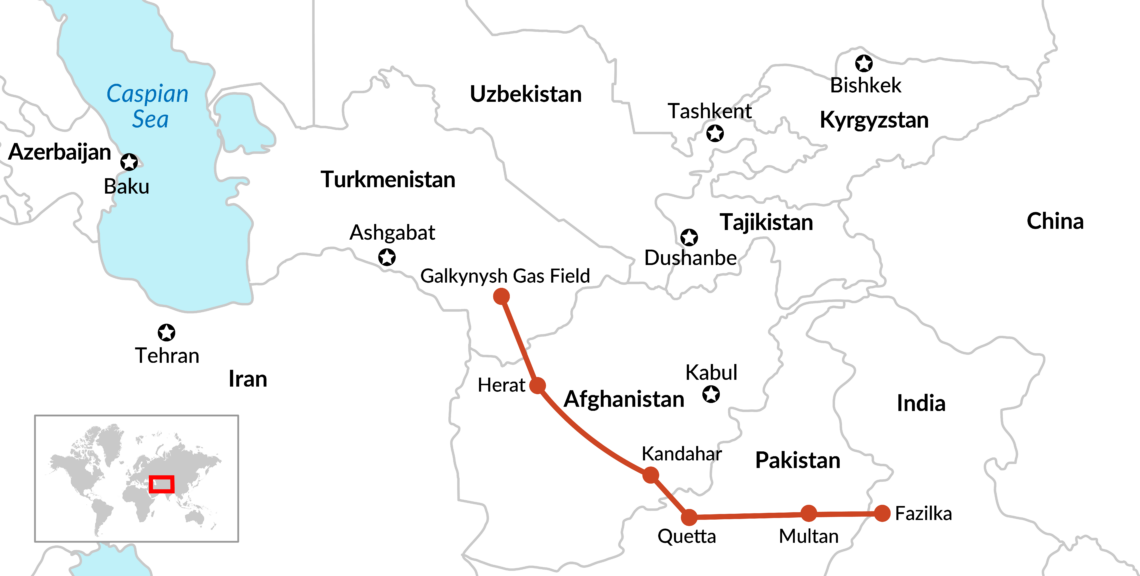

Faced with these developments, Ashgabat has begun eyeing its ace in the hole – a new pipeline that would take natural gas from Turkmenistan across Afghanistan to Pakistan and India. Known as TAPI (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India), the pipeline would cost $10 billion, be 1,814 kilometers long and have a capacity of 30 billion cubic meters.

The project has been in the news before but has always faltered because of security issues in Afghanistan. This time around could be different. A recent secretive visit by the Taliban to Turkmenistan suggested that important moves may be underway.

According to a statement from the Turkmen Foreign Ministry, the talks concerned not only TAPI but also a Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan (TAP) power line and rail connections between Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. Most importantly, a delegation member was quoted stating that “we declare our full support for the realization and security of the TAPI project and other infrastructure projects in our country.” In April, both governments signed a security concept for the construction of the pipeline.

Uzbekistan

Another optimistic development is that Uzbekistan is getting ready to commit. When talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government began, the head of the Taliban movement’s political office in Qatar, Abdul Ghani Baradar, who also led the recent delegation to Ashgabat, pledged that no threats to Uzbekistan would be allowed to emerge from Afghanistan. And he vowed to support Uzbek economic projects inside the country.

Banking on this promise, Uzbekistan Railways recently announced the launch of a high-speed freight train service from Tashkent to the Afghan border, cutting travel time from five or six days to two. The opening of an international transport corridor with access to seaports in South Asia and the Middle East would enhance the role of Uzbekistan in the BRI.

The weak link in the chain is Turkmenistan. A commitment by outside investors to large infrastructure development would help stabilize Afghanistan, potentially persuading the Taliban to enter into some form of power-sharing agreement with the government. A large inflow of capital might also prevent the Turkmen economy from collapsing. Economic rationality thus dictates that all sides should commit. But Turkmenistan may hesitate.

Cutting a deal with the Taliban would mean presenting a credible commitment by outside investors, which in turn requires at least some degree of transparency and compromise. In the past, the Turkmen government’s stance has stalled infrastructure projects. Long-standing plans to construct a Trans-Caspian pipeline have not come to fruition because Ashgabat refused to offer outside investors access to upstream resources. Its troubled relations with Uzbekistan would also need to improve, if the two are going to move in tandem.

Perhaps the main obstacle to unlocking the potential of a big deal does not lie with the Taliban after all, but rather with Turkmenistan, which is so obviously fearful of what might follow after opening the country to outside influence.