Beidou: Assessing China’s alternative to GPS

The third iteration of the Chinese satellite navigation system, Beidou, is now nearing the capacity of the United States’ GPS system. This technological advance will shield the Chinese military from further American attempts to disrupt navigation.

In a nutshell

- Beijing has enhanced its military capabilities by deploying its own navigation system

- Beidou will gradually replace GPS on the Chinese market and expand globally

- The navigation system could be a stepping stone to China’s space ambitions

At the annual meeting of the International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (ICG) in December this year, China declared that its Beidou Navigation System (BDS) would be fully operational in 2020. Beidou in Chinese stands for Northern Dipper – the name used in ancient China to refer to the seven brightest stars of the Ursa Major constellation. Historically, this set of stars was used in navigation to locate the North Star.

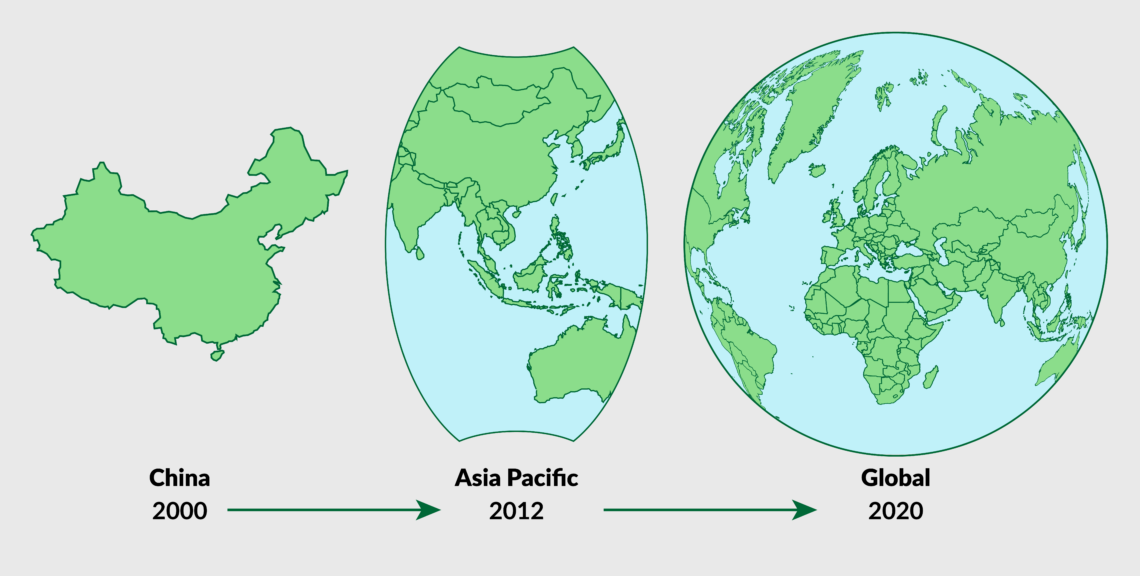

Since the late 1990s, when the first BDS satellite entered orbit, 53 system satellites, including four experimental ones, have been launched, and several have been retired. BDS began providing positioning, navigation, timing and messaging services to civilian users in China and parts of the Asia-Pacific region in December 2012. Now, eight years later, it has finally achieved global coverage.

Ambitions

China’s ambition to build its own navigation system dates back several decades. In the 1990s, two incidents served as a wake-up call for Beijing.

The first occurred on July 23, 1993, when the United States alleged that the Yinhe, a Chinese cargo freighter, was carrying materials for chemical weapons to Iran, and threatened to impose sanctions on China. In the end, the American inspection did not find any chemical weapon materials on board the ship. Yet the scheduled voyage had to be suspended for 33 days. When the U.S. Navy tried to stop the cargo freighter for inspection in the Indian Ocean, the crew simply ignored the request. As a result , the U.S. shut down its Global Positioning System (GPS) for the region, stranding the ship. From the viewpoint of the Chinese government, this was a drastic display of American hegemonism and power politics.

In the 1990s, two incidents served as a wake-up call for Beijing.

Another noteworthy event took place in 1996, at a tense moment between Beijing and Taipei because of former Taiwanese president Lee Teng-hui’s proposal that relations be conducted on a “state-to-state” basis. This was seen by mainland China as a move toward full independence. Therefore, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) subsequently carried out a large military exercise and fired three missiles into the East China Sea, only 18.5 kilometers from Taiwan’s Keelung military base, as a warning.

The first shot was on target. However, the PLA lost track of the second and the third one. Later on, China’s military analysts came to the conclusion that the two failures could have been caused by a GPS disruption. For the PLA it was an unforgettable humiliation.

Having learned from these two lessons, China accelerated its pace to carry out its navigation system project. The Chinese government mobilized more than 100,000 researchers and engineers from some 300 institutions to this effect.

Beijing completed BDS-1 at the end of 2000, providing service in China. BDS-2 was operational at the end of 2012, providing service to the Asia-Pacific region. BDS-3 is expected to be finalized this year, providing service to users around the world. China reportedly spent $2.57 billion on the Beidou program from 1994 to 2012 and planned (as of 2013) to spend an additional $6-8 billion from 2013 to 2020 – one of the largest space programs the country has undertaken.

Strengths and weaknesses

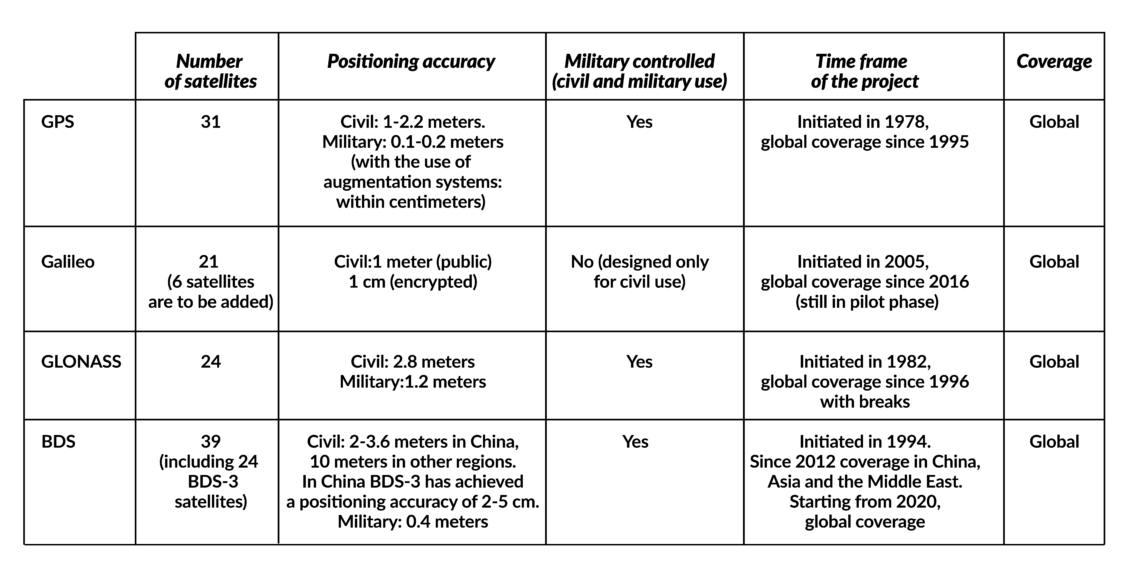

Prior to BDS, there were three Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) in the world. GPS is the most widely used, while Russia’s GLONASS and the EU’s Galileo trail behind, mostly because they still have not reached the same level of sophistication.

Facts & figures

As shown in the chart above, GPS is currently accurate to the centimeter rather than to the meter like the Chinese system. BDS offers a location service with an accuracy of 2-3.6 meters within the Asia-Pacific region and 10 meters in other parts of the world, although for China’s military, BDS’s licensed service could have a much greater accuracy.

Unlike the other GNSS technologies, the fully-operational Beidou network will include eight spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit, with five permanently over the equator and three others in inclined orbits that swing north and south of the equator during each 24-hour orbit. This already gives China some room for further improvement. In addition, with the increase of differential ground stations outside the country, China will be able to make its location service more efficient. Beijing is catching up with the global standard.

One important feature of BDS-3 is its high degree of localization, meaning that the key components of BDS-3 satellites are designed and produced by Chinese companies. This is part of the government’s decoupling policy so that China will not be dependent on foreign supply chains, especially on components from the U.S. For example, BDS-3 functions with China’s own cutting-edge rubidium atomic clocks and passive hydrogen maser clocks with better intersatellite connectivity. Finally, in addition to navigation, positioning and timing, BDS provides services such as a short messaging platform. China claims that the positioning accuracy of BDS is even better than that of GPS, and that it will be compatible with smart terminals. The latter is important for digitized industries, like autonomous driving.

However, according to the BBC, BDS could have a flaw – a two-way transmission process that involves satellites sending signals to earth and devices transmitting signals back. This could compromise accuracy and takes up more spectrum bandwidth. In contrast, GPS devices do not have to transmit signals back to the satellites.

Like the American government in the 1980s, China will commercialize its service by giving priority to the military, then gradually extending it to various production sectors and to everyday use.

Military implications

BDS has become a vital part of President Xi Jinping’s strategy to develop a smarter military. Notably, the Chinese armed forces are now less reliant on GPS. Beidou satellites, in the event of a conflict, will enable China to identify, track and strike enemy ships, increasing their tracking ability by 100 to 1,000 times. China can deploy precision-guided munitions in large quantities to strike accurately. Accordingly, the success rate of attacks by the PLA’s navy and air force will be significantly increased.

Security expert Jordan Wilson believes that Beidou could pose a security risk by allowing China’s government to track users with malware transmitted through either its navigation signal or messaging function (via a satellite communication channel), once the technology is in widespread use.

Via the short messaging service, Chinese fishing vessels can send instant alarms to fishing departments when emergencies arise, while a vessel management system allows them to request assistance from nearby vessels. All the features mentioned above are particularly relevant to the ongoing disputes in the South China Sea and Beijing’s plan to regain Taiwan by force.

Commercial implications

Based on the American forecast, GNSS use will grow 7 percent annually on average through 2023, with 3.6 billion GNSS devices in use worldwide. The total output of China’s navigation service sector exceeded 25 billion dollars in 2015. It is expected that BDS will generate 298 billion dollars by 2020.

In 2012 the United States led with 31 percent of the total downstream GNSS industry, followed by Japan with 26 percent, Europe with 25.8 percent, and China with 7 percent. BDS’s penetration rate in China is still very low: 95 percent of the domestic market is dominated by GPS. However, this situation will change once BDS offers global coverage. China aims to reach 60 percent of the domestic GNSS market in order to become globally competitive by 2020.

BDS has become a vital part of President Xi’s strategy to develop a smarter military.

Chinese press reports tout a variety of uses for BDS, including public security, transportation, fishing, energy, forestry, disaster reduction, smart cities, social governance and more. Numerous pilot projects have already been tested. A new BDS-related supply chain of more than 14,000 enterprises and 45,000 employees is emerging.

As part of its digital Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is promoting the use of its GNSS in Central Asia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. ASEAN countries will be a priority for expansion. Both sides have launched a set of “China-ASEAN urban demonstration projects.” Beijing has signed agreements with Central Asian countries and countries from the Middle East to bolster research and application development of BDS throughout the region – thus definitely increasing the likelihood of those countries using the system for all of their positioning, navigation, and timing needs. Also, Africa will begin utilizing BDS, which could in turn give China additional leverage as it looks to secure mineral and resource rights throughout the continent.

Economic diplomacy

China strives to become a world leader in space, and BDS will provide it with extra leverage in several international and regional organizations such as the International Telecommunications Union, the International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems and the International Civil Aviation Organization.

Along with the digital Silk Road, Beijing will construct a network of differential ground stations throughout Asia – perhaps up to 1,000 and 80 in Southeast Asia alone – to increase the system’s local accuracy. In Asia, Thailand, Brunei, Laos and Pakistan, to name a few, already use BDS-equipped infrastructure for government and military users.

Love-hate alliances

In 2004, China invested 280 million euro in the EU’s Galileo, three years after the creation of the system. Beijing’s intention was obvious: by that time, China still trailed behind the technology of all the great powers. It hoped to absorb European technologies via investment, and planned to build its own GNSS for Asia only.

Relations between the two sides went sour afterward. Both felt exploited. Europe complained about China stealing technology, while the Chinese believed Europeans treated them unfairly. Consequently, Beijing withdrew from the Galileo project in 2007.

Russia and China have been increasingly moving toward greater synergy between their respective satellite navigation systems.

Russia and China have also been increasingly moving toward greater synergy between their respective satellite navigation systems as of 2015 or earlier. GLONASS is fully operational since 1996. In the following years, however, the project repeatedly struggled with age-related technical failures, and it could not function fully. In 2008 the project was renewed with additional funding.

A decisive move toward cooperation was made in July 2019. Russia passed a law entitled “On the ratification of the agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on cooperation in the use of GLONASS and Beidou global navigation satellite systems for peaceful purposes.” This will lead to “large-scale cooperation in the satellite navigation field between the two countries.” It is part of an ongoing effort to virtually combine the two systems and replace GPS as the leading global navigation system. This has far-reaching geopolitical implications and could impact GPS operations globally.

The emergence of BDS will create a new race in satellite systems for position determination and navigation.

Scenarios

As a technological latecomer, China is quite aware of its disadvantages while competing with GPS. Since it is the ultimate goal of the political elites to replace GPS in at least some key sectors, Beijing will deploy all means necessary – including some nonmarket approaches to form a BDS-related supply chain and service sector – to accelerate the pace of commercialization. With time, the market share for other GNSS technologies, especially GPS, will likely decrease with the expansion of BDS. A combined effort between China and Russia will threaten GPS’s dominance around the world. In this sense, China is a competitor.

The precondition for conquering the market is always better technological capacity. Accordingly, like with the 5G network, the emergence of BDS will create a new race in satellite systems for position determination and navigation, especially between China and the U.S.

Simultaneously, cooperation has become a trend. Generally speaking, the satellite navigation industry is heading toward “multi-constellation” receivers that work with all GNSS. It is also the ultimate goal of the International Committee on GNSS of the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs “to achieve compatibility and interoperability of GNSS systems.” This development will bring greater accuracy to consumers at minimal marginal cost and is supported by governments around the world. China began its bilateral consultations on civil cooperation with other existing GNSS technologies in 2014. Beijing and Washington also signed a cooperation agreement in 2017. There has been interaction between the EU and China regarding Galileo and BDS cooperation.

The success of BDS has largely enhanced China’s capacity for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. Jamming and spoofing GPS in the event of tensions between the U.S. and China will have tactical and strategic advantages for Beijing. It might help support a specific mission or goal, such as harassing U.S. Navy war games or protecting China’s presence in the South China Sea. In this context, the creation of a full-fledged U.S. Space Force within the Department of Defense in 2019 was a sensible move. The U.S. will be struggling for military dominance in space. Also, NATO decided in June 2019 to develop its first space strategy to meet challenges posed by Beijing and Moscow. China will inevitably be considered a potential adversary for the Western world.

In view of the abovementioned developments, political and business acumen will be required in handling the rise of Beidou.