Rough waters ahead for Chile’s new government

Chile faces economic uncertainty as global trade alliances are thrown into disarray. The new government in Santiago has a weak position in the legislature. On top of the challenges of diversifying Chile’s copper-based economy, President Pinera must deal with social unrest.

In a nutshell

- Latin American faces new risks and opportunities as the U.S. seeks to realign global trade flows

- The agenda of Chile’s conservative president is concentrated on domestic economic reform and spurring growth

- His government must also deal with disruptive social changes

Over the next several months, Chile’s economy will navigate uncertain terrain, as global markets have been thrown into disarray by new trade policies of the United States. With a skillful approach, Chile could take advantage of this historic moment to solidify its economic growth and enhance its international influence. However, Chile’s President Sebastian Pinera, whose honeymoon period after the reelection is drawing to a close, is also facing very difficult political challenges at home.

A free-market conservative and well-to-do businessman with a Harvard degree, Mr. Pinera is a known quantity in Chilean politics. His technocratic style and laissez-faire beliefs would be well suited to a period of stability when heads of state can succeed by routine governance. But that is, of course, not the situation in which the president of Chile finds himself. Mr. Pinera will need to spend much political energy overcoming the limitations posed by his government’s minority position in the legislature before he tackles the challenges of profound international uncertainty.

New alliances

It is still unclear how an escalating trade war between China and the U.S. will affect Latin American economies or how potential meltdowns among emerging economies, such as Argentina or Turkey, will shake up the region’s financial institutions. One outcome, however, is already visible: Latin America’s leaders have been spurred to seek out other trade partners, especially among their neighbors.

Chile has stable banking institutions and regulatory transparency, which are lacking in many emerging markets.

At the end of April 2018, President Pinera traveled to Brasilia to sign a new free trade agreement with his Brazilian counterpart, President Michael Temer. Also, the Pacific Alliance, a trade bloc consisting of Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru that accounts for half of Latin America’s exports, voted to admit new associate members from across the Pacific, including Australia, New Zealand and Singapore. Not long ago, full South American regional trade unification would have been unthinkable, but the Pacific Alliance and Mercosur are considering agreements that would profoundly reshape intra-Latin American trade patterns. Working in Mr. Pinera’s favor, Chile has stable banking institutions and regulatory transparency, which are lacking in many emerging markets.

More importantly, U.S. President Donald Trump’s unpredictable political stands will lend legitimacy to the rise of China in Latin American markets. China is already Chile’s most important trading partner, but erratic signals from Washington will likely lessen any lingering geopolitical concerns that have accompanied China’s ever-growing reach into the Western Hemisphere. This is particularly important to Chile as China’s Tianqi Lithium Corp. just bought from the Canadian company Nutrien Ltd. a 24 percent stake in Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile S.A. (SQM), the Chilean mining firm sitting on top of what may be the largest lithium reserve in the world. The Chilean Development Agency (CORFO) had tried to block the sale, but it went through after the Chinese government applied pressure on the Pinera government.

Easier said than done

Copper dictates Chile’s fortunes. Despite the lofty promises of President Pinera and his predecessor, Michelle Bachelet, to diversify the economy and find new trading partners, global copper prices continue to be the most critical determinant of Chile’s economic strength. Copper prices fluctuated in the first half of 2018. Downward pressure resulted from investors’ worries that U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum, while not applying directly to copper, would weaken China’s demand for it as well; this demand is the key driver of global markets. On the other hand, supply security concerns related to ongoing labor negotiations at mines owned by CODELCO, the Chilean state mining company, caused prices to rise.

The possibility of strikes at Chilean mines – particularly Minera Escondida Ltda., the highest-producing copper mine in the world – has investors jittery, especially in the wake of a Brazilian truckers’ strike that reminded policymakers across Latin America of the power of organized labor to bring an economy to a standstill. Neither weaker Chinese copper demand nor decreased Chilean supply bodes well for Chile in 2018. The urgency of economic diversification is apparent. New and vital trade relationships with Latin American partners may provide one driver for such a diversification.

Central to the president’s election campaign were two economic promises. The first was that his administration would double the economic growth rate seen under his predecessor – it was 1.6 percent in 2017. Thus far, with the latest (May 2018) OECD growth forecast for Chile at 3.6 percent, and the economy growing at an annual rate of 5.3 percent in the second quarter, Mr. Pinera appears to be on pace to deliver on that promise.

The president emphasized the need first to reduce Chile’s fiscal deficit by cutting nearly $5 billion from state budgets.

Wisely, he has reneged on his second campaign promise: to lower the corporate tax rate from 27 percent to 24 percent, as it stood when Mr. Pinera previously held office in 2010-2014. The president emphasized the need first to reduce Chile’s fiscal deficit by cutting nearly $5 billion from state budgets over the course of his term.

Enter the students

Mr. Pinera’s still young second presidency is already showing worrisome similarities to his first term in office. In that period, his efforts to liberalize, modernize and diversify Chile’s economy were overshadowed by crippling student protests, primarily fueled by anger at private, profit-seeking institutions of higher education. Between 2011 and 2013, Chile’s student-led social movement became one of the most prominent in the world. The students demanded the elimination of school fees and of a voucher system that, they claimed, produced vast inequalities in educational outcomes. Ultimately, President Pinera’s slow and clumsy response to the protesters crippled his government and contributed to the election of Mrs. Bachelet in 2013.

Now, just months into his new term, upheaval and anger at Chilean universities are once again demanding attention. Protesters are indignant that the Chilean Constitutional Court reversed legislation intended to limit the influence of for-profit corporations on higher education. The reversal, of course, was not the president’s decision, but he would be wise to come to terms with the younger generation of political activists who have formed a new party, the Broad Front (Frente Amplio, FA) which is separate from the old parties on the left. To placate this growing opposition, Mr. Pinera already made a telling cabinet change. He replaced Gerardo Varela, his trusted minister of education who insisted that the state should not be involved in education reforms (a position rejected by most Chileans) with Marcela Cubillos, who is better attuned to the expectations of the younger generation.

Women, too

More prominent, and more novel, is a wave of protests by female students, a sort of globalized #MeToo movement playing out at Chilean universities. The so-called Toma Feminista, or Feminist Takeover, has left some Santiago universities shuttered for weeks. In particular, the occupation of the administrative buildings at Santiago’s storied Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, known as PUC, has attracted media attention and widespread support.

President Pinera has always remained aloof from social issues while resisting the more extreme social-policy demands of his right-wing base. The Toma Feminista is representative of broad, sweeping changes in Chilean society. Questions of gender and sexual identity have gained much prominence in a country so steeped in Catholicism that it did not legalize divorce until 2004. Also, Chile’s Catholic Church has become embroiled in sex scandals, which lead to the pope’s acceptance of resignations from three discredited Chilean bishops. Among many Chileans under 30, the Catholic Church is no longer viewed as having the moral authority to dictate social norms.

This shift has a profound impact on the Christian Democratic Party, which for many years was the country’s second largest. It now finds itself caught between the two major coalitions: Mr. Pinera’s Chile Vamos and the Nueva Mayoria, which leads the opposition. The Christian Democrats are conservative on issues such as abortion, gender and education, but more progressive on the questions of human rights, poverty and inequality. They support the so-called “social market” agenda.

Indigenous protests

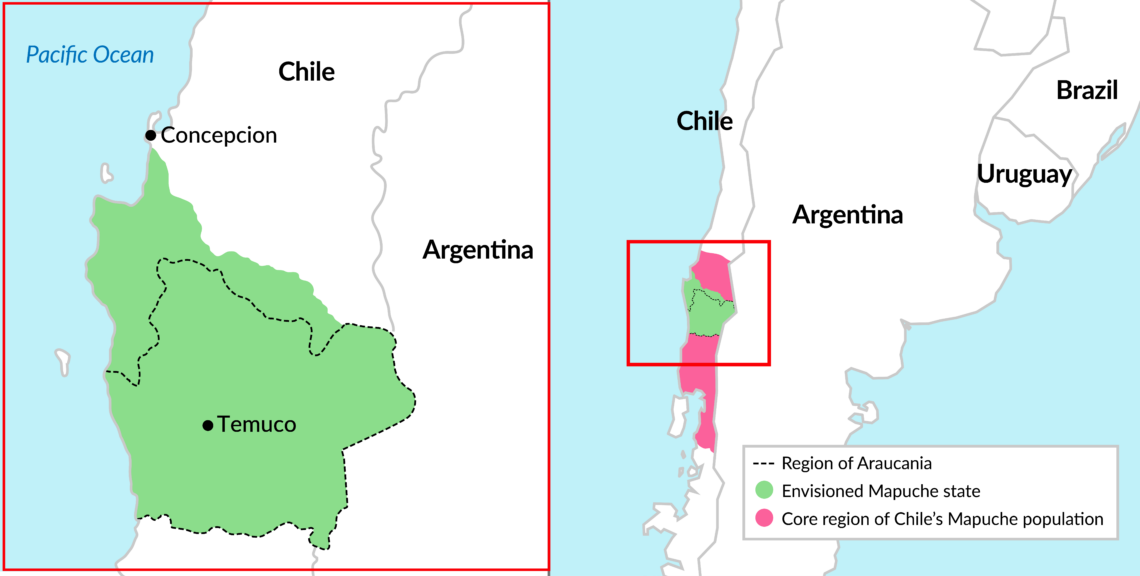

During the election campaign, candidate Pinera also vowed to deal with the increase in violent “terrorist conduct” in Chile – in particular, recent protests carried out by indigenous Mapuche groups in the southern Araucania region. The decision to refer to Mapuche violence as terrorism was a rhetorical choice laden with consequences. Many on the left regard the anti-terror laws that grew out of the Pinochet era (1974-1990) as outdated and repressive. Also, a group of United Nations experts has urged Chile to prosecute Mapuche protesters under the regular criminal laws, rather than anti-terrorism statutes. The experts’ fear has been that the indigenous community is being mistreated, especially in the context of local conflicts over land rights.

Facts & figures

The Mapuche people are demanding recognition of their rights to land and self-governance

Immigration quandary

Questions of immigration will also loom large in Chile during the coming year. Mr. Pinera has already demonstrated a tendency to placate anti-immigration hardliners. Over the past decade, immigration to Chile has skyrocketed. About 1 million immigrants are now estimated to live in Chile, a country of 18 million. That is nearly triple the number of 10 years ago. Rapidly rising immigration rates – especially the influx of Haitian immigrants, who are typically black and do not speak Spanish – have provoked a backlash. President Pinera shows no qualms about exploiting these volatile sentiments.

Under new presidential decrees, migrating to Chile is also going to become harder, especially for Haitians. Applicants of this origin will need to have visas – a 30-day tourist visa at the very least – to enter Chile. There are also new visa requirements and immigration rules for Venezuelans seeking to migrate to Chile.

The president appears to lean toward pragmatic difference-splitting on most issues.

In reality, however, Chile needs immigration. The country’s unemployment rate is low and labor shortages are impeding vital economic sectors. The population is aging and its total fertility rate (1.81) has fallen below the reproduction rate. Restricting immigration at such a juncture reflects only fear and shortsightedness on the part of the Chilean public and its leaders.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario in the next six to 12 months is that President Pinera will tack to the center and seek to strengthen his support in the legislature. This is essential for the government to push the key elements of his agenda concentrated on economic development.

With only 72 out of 155 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 19 of 43 in the Senate, Mr. Pinera needs votes from nonconservatives. The opposition parties, although fragmented, could seize on the government’s weak position to block Mr. Pinera’s legislation and try to ride out his term without allowing changes to Chile’s political economy. To forestall that, the president appears to lean toward pragmatic difference-splitting on most issues. He has supported a compromise on the nation’s minimum wage hike, demanded by the National Congress, and accepted the resignation of his freshly appointed culture minister, who seemed sympathetic to the remaining supporters of the Pinochet dictatorship. In both cases, the government won support from the swing votes in Congress, the Christian Democrats and the Broad Front.

There are two less likely scenarios. One has the opposition finding a way to coordinate their agendas and forcing Mr. Pinera to accept positions to his left on social and economic matters. While this script indeed is possible in the long run, it does not seem very likely in the near term. Virtually all of the parties that formed the governing New Majority coalition under Mrs. Bachelet are going through intense soul-searching and internal debates. Their activists are split between those who want to bargain with the government and those who insist on a rigid defense of their values and principles.

Another less likely scenario would see Mr. Pinera following the example of his foreign minister, Roberto Ampuero, and trying to establish himself as an important regional figure, spearheading the creation of free trade alliances that would unify the South American continent and reach across the Pacific. In doing so, the president could build on the base created by the Concertacion governments after the fall of Augusto Pinochet. This would effectively help insulate Chile from the caprice of Mr. Trump and lay the foundation for a Chilean economy less susceptible to the whims of global copper prices. This scenario may become more likely over time if Mr. Pinera feels stymied or frustrated in getting his agenda through Congress.