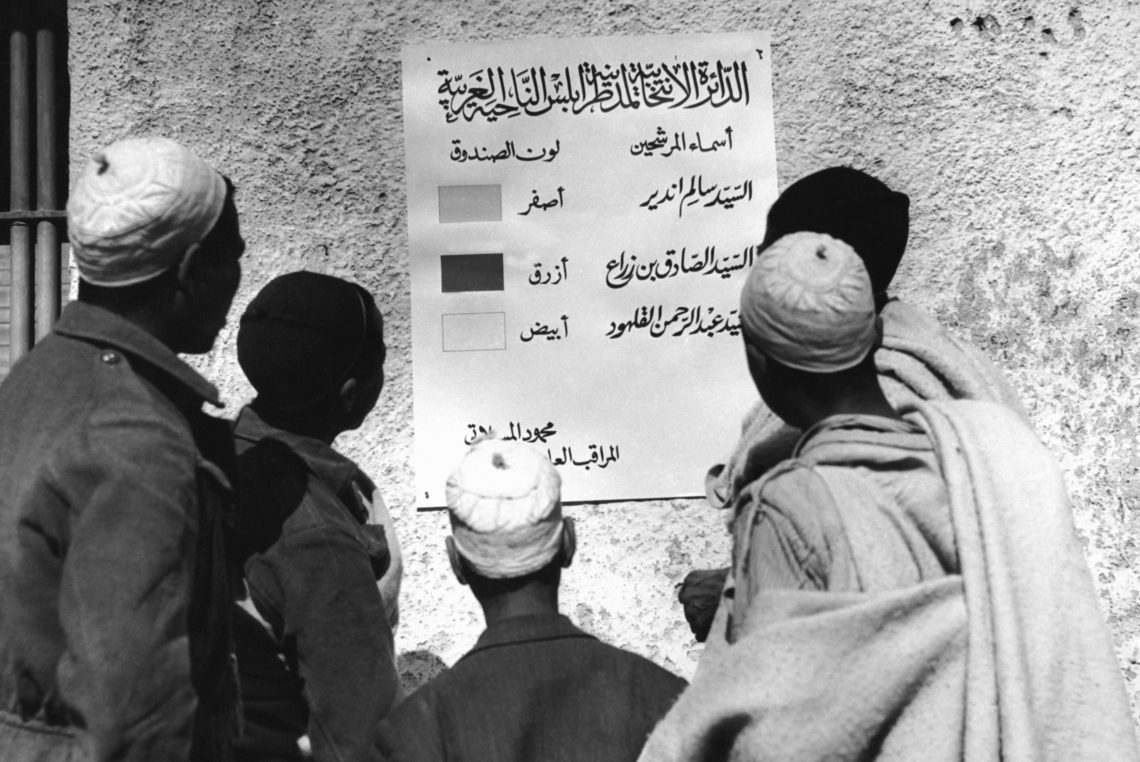

The chimera of elections in Libya

Putting dreams of democracy ahead of real-world stability, international efforts for new elections in Libya have so far failed. A ballot is unlikely to take place in the foreseeable future.

In a nutshell

- Successive efforts to hold new elections in Libya have failed

- The country still lacks the strong institutions necessary for democracy

- Libya’s leadership will likely feign cooperation on any planned ballot

There has been much talk about elections in Libya in recent years. The topic seems to have become an obsession for a group of diplomats and politicians – generally Western rather than Libyan – starting at the Paris Conference in July 2017, when speculation arose that a vote could be held within months. This well-intentioned hope was buttressed in May 2018, with a tentative election date set for December 10 of that year.

Many, however, particularly in Tripoli, took issue with the proposed timing and procedures. Their disagreement became apparent with the violent response of the Tripoli militias between August and September of 2018.

In February 2019, the international community made another attempt in Abu Dhabi. The response this time came from Libyan Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, the military arm of a House of Representatives elected way back in 2014 – the most recent Libyan elections – and subsequently relocated to Tobruk that same year. Mr. Haftar’s group of eastern militias, known as the Libyan National Army (LNA), attempted to seize the capital just two months after the Abu Dhabi conference. This resulted in a siege that lasted for over a year, causing unnecessary death and despair.

This situation led to the resignation in March 2020 of the United Nations Special Envoy for Libya, the Lebanese professor Ghassan Salame, a man who had become profoundly disillusioned. Under the interim leadership of the American Stephanie Williams, the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) has focused on fostering inclusive dialogue among various Libyan factions. This effort materialized by late 2019 in the form of the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF), whose main goal was to “generate consensus on a unified governance framework and arrangements leading to national elections within the shortest possible time frame, thereby restoring Libya’s sovereignty and the democratic legitimacy of Libyan institutions.”

Read more on Libya

Europe’s mistakes in Libya

Nation divided

December 24, 2021, was set as the tentative election date, but it was not specified whether the elections would be presidential, parliamentary or both. Furthermore, there would be no updates to the electoral law and, importantly, no constitution. It was unclear what powers the president and parliament would hold in a highly unstable environment where the state did not have a monopoly on force. At that time, the nation was divided between the HoR in Tobruk and the newly formed Government of National Unity (GNU), voted into power by the LPDF and installed in March 2021 with Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh as prime minister. This government was supposed to see the country through to the end-of-year elections and then yield to a new administration. Despite UNSMIL’s goodwill, many observers believed this would require a miracle – one that did not ultimately come.

With only a few days to go before the proposed election, there was still no official list of candidates, and no substantial electoral campaign had been initiated. And so, the long-anticipated elections were not held, despite the nearly three million citizens registered at polling stations. What was lacking was the will of Libya’s political class, which had been significantly stripped of its powers over the years.

The situation did not improve following this umpteenth political failure. Firstly, Mr. Dbeibeh refused to relinquish his position as the head of the GNU. This sparked the ire of the HoR, which appointed Fathi Bashagha, former interior minister of the previous Tripoli government, as its prime minister. After fighting vehemently against the Haftar siege, Mr. Bashagha decided to change allegiance and move to Cyrenaica, where the parallel Government of National Stability was born. This further deepened the divide between the two Libyan political entities and pushed the country closer to formal division, as evidenced by the duplication of fundamental institutions like the Libyan Central Bank.

The international community, faced with this latest failure, has not taken a clear stance, attempting to appease both sides. The ensuing months were filled with a barrage of accusations and offenses exchanged between the two factions. The international community, faced with this latest failure, has not taken a clear stance, attempting to appease both sides. The ensuing months were filled with a barrage of accusations and offenses exchanged between the two factions. But, in the end, Mr. Bashagha’s decision appears short-sighted, given how it was torpedoed by Field Marshal Haftar himself. On May 16, the HoR agreed to suspend the former prime minister and investigate him for failing to perform his duties.

On September 2, 2022, the new Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Libya and Head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya was appointed: the Senegalese politician Abdoulaye Bathily. His intention was immediately clear: to arrange elections for Libya as soon as possible, because “giving the Libyan people the opportunity to choose their leaders through the ballot box is, without a doubt, the way towards peace, stability, and prosperity in the country. Elections are needed to restore and rebuild legitimate public institutions that represent and serve the people of Libya.”

Mr. Bathily worked tirelessly for the next five months, speaking and meeting with parties in Libya and in the foreign offices of some of the concerned countries. He pushed for the creation of a fundamental constitutional basis for the elections. Following his lead, the HoR and the High Council of State in Tripoli, after adopting a legislative document – the 13th Amendment – appointed a joint “6+6” commission to deliberate on electoral laws. An electoral steering committee, composed of up to 40 Libyans from all elements of society, was also formed to pave the way for the elections. This committee is tasked with addressing the constitutional basis for the electoral law as well as the security situation.

Mr. Bathily’s plan is to establish a clear road map for the elections by mid-June. On paper, everyone agrees to hold them as soon as possible, likely by the end of the year. But how different is the current situation from that of 2021?

Institutional vacuum

According to the 2019 Fragile State Index, Libya had a ranking of 92.2 out of 120 (with Finland being the best-rated state at 16.9 and Yemen the worst at 113.5). Today, Libya’s score is 94.3, indicating a further decline. Currently, the country does not have one stable government, but rather two in fierce competition with each other. It lacks an institutional framework capable of managing any tensions between factions resulting from the vote, let alone an executive with a monopoly on force. What it does have is a political class that is ill-equipped for the task at hand and is so far uninterested in yielding to others; a multitude of heavily armed militias; and still significant work to be done in terms of a constitution. It is worth remembering that institutions, not elections, are the backbone of a stable modern democracy.

Furthermore, how will freedom of movement for candidates be guaranteed during the necessary electoral campaign? How will presidential candidates from Benghazi make themselves known in Tripoli, for example, if the security issue is not resolved in the coming weeks? And if a runoff occurs, will polling stations be targeted for attacks? While Mr. Bathily’s efforts are encouraging, many of these questions still require realistic answers.

Scenarios

Elections this year

This scenario, although it is the goal of UNSMIL, is highly unlikely unless certain issues are resolved. Tellingly, the country’s second civil war started just after the last election in 2014. Those results were heavily contested, and there was no international organization ready with evidence to validate the vote. What preparations are being made for elections that should take place within a few months? And how will the militias, which have been entrenched in the field for years, conduct themselves? Without clear and practical answers from UNSMIL to these crucial questions, elections could deliver nothing but more catastrophe for Libya.

No elections in 2023

While a government legitimized by fair elections would be an extraordinary gift for Libyans and could indeed address yet unresolved issues such as divided central institutions, corruption and a new constitution, achieving all this is extremely challenging. It would undermine those same parasitic entities that have thrived in this dysfunctional quagmire: the current ruling class and militia leaders. It is therefore much more likely that the Libyan leadership will feign cooperation, only to sabotage the process as they did in 2021.

Elections after 2023

Although Mr. Bathily has not yet proposed a detailed plan, suggesting that elections will not take place in the coming months, there is an unlikely possibility that efforts will continue to support them. However, for the election to be a success, it is essential that all spoilers are definitively resolved, and that there is extraordinary attention paid to ensuring each electoral step, especially those following the elections. Reflecting on the past 12 years, this scenario also appears to be a chimera for Libya.