Europe’s mistakes in Libya

Europe overestimated the prospects for rapid democratic transition in Libya, and will likely continue to face successive crises without a long-term strategy.

In a nutshell

- European efforts have failed to stabilize Libya

- The security situation has worsened

- Politicians and militants benefit from the status quo

Europe failed Libya. As the internal situation in the country began to unravel in 2011, Europe had the opportunity to intervene and stabilize the deteriorating civil and security situation there. Instead, the ad hoc military attack that occurred, followed by the subsequent NATO operation against the forces of Muammar Qaddafi, only accelerated Libya’s descent into instability.

Civil wars

In early 2011, the Arab Spring uprisings swept across the Middle East-North Africa region. For some countries, like Libya, they acted like a tsunami – sweeping away existing regimes and returning several times to the same disaster area, each time bringing political, economic and social catastrophe.

The first uprisings in Libya broke out in Cyrenaica, between Tobruk and Benghazi, but then spread to Tripolitania, where they were violently suppressed with bloodshed. The international response took the form of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which called for the use of every possible means to protect Libyan citizens, but not for regime change. The bombing of Libya began on March 19, 2011, as a unilateral decision of incumbent French President Nicolas Sarkozy, later developing under the NATO umbrella as Operation Unified Protector. This ended shortly after the October 20, 2011, capture of Muammar Qaddafi and his brutal killing. The dictator’s 42-year rule had come to an end, but nothing assured that what followed would be any better.

The UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), which was supposed to help the country in its arduous transition from autocracy to democracy, was activated almost immediately on September 16, 2011. But this did not guarantee success. The challenges were numerous and touched the pillars of any functioning state: economy, politics and security. The last one proved to be the most devastating. During the war, Qaddafi’s armaments depots, overflowing with light and heavy weapons, had been pillaged; despite the embargo, the population – which during the regime was not permitted even to approach these extensive arsenals – found themselves awash in weapons. Some of these stayed in Libya, while many others spilled over into international arms trafficking rings.

The situation did not improve over the years. In 2016, there were an estimated 20 million weapons in Libya for only 6 million people. The arms flowed through various channels, ending up in the hands of terrorists and local militias, mainly through the country’s porous borders. The trafficking and use of these arsenals gave Libyan militias the opportunity to develop their own status within the country’s broader social fabric. Weapons that should have been handed back at the end of the revolution remained in their hands, increasing the political clout of those fighters who, year after year, found an ideal base in a state lacking the monopoly of force.

Read more from Federica Saini Fasanotti

What role for Europe in the Middle East and North Africa?

With Qaddafi’s death, and the sudden collapse of the regime, Europe was faced not only with the urgency of confirming all the contracts signed with Tripoli in previous years but also with the age-old problem of uncontrolled migration. Qaddafi had clearly known this, and, over the decades, used it as leverage. By the beginning of the new millennium, he had become a major player in multilateral discussions on the issue of migration. His fearmongering over a supposed “black Europe” resonated with European public opinion and, consequently, with the continent’s political class. Italians in particular found themselves making many concessions to Qaddafi precisely because of this. The Libyan leader took a similar line on migration at home; at least on (constitutional) paper, African refugees were not protected in the country, and the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol were never signed.

Then, when the revolution overthrew Qaddafi, the gateway to Europe lost its gatekeeper. Operation Hermes 2011 – the EU’s coordinated efforts on joint border patrols, linked to the 2009 Return of Illegals Directive – was not long in coming, but its results were minimal. Three years passed without a stable government in Libya, with an increasingly pronounced division between the Tripolitania and Cyrenaica regions. That led to another civil war in 2014 and the displacement of the House of Representatives to Tobruk.

After months of negotiations between the General National Congress (GNC) in Tripoli and the House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk, in December 2015, UNSMIL got the warring parties to reach the Skhirat Political Agreement, which proposed a Government of National Accord (GNA) chaired by Fayez al-Serraj as prime minister. The GNA immediately showed itself to be extremely weak in the face of the criminal cartels of the Tripoli militias. The GNA had taken office without actually resolving the complex issues of security and a state incapable of maintaining a monopoly on force. Instead, Libya faced an oligopoly of violence, with force distributed through various channels.

The situation in Cyrenaica was different but no better. There, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar – an old Qaddafi acquaintance who, after the defeat of the Libyan army in Chad in the 1980s, decided to switch sides by collaborating with the Central Intelligence Agency – developed his own force, the Libyan National Army (LNA), from a patchwork of militias, to serve as the armed wing of the HoR.

Deep divide

These divisions, which have become more pronounced over time, have also sharply defined the supporters of the two factions. The GNA in Tripoli, backed by UNSMIL, was theoretically supported by the international community. But while Italy has taken a consistent stance regarding the UN’s choices – as has the United States – other nations, such as France, Russia, the UAE and Egypt have secretly supported the HoR and its armed LNA wing. In April 2019, Mr. Haftar’s LNA, after a long march of thousands of kilometers across the Fezzan desert, laid siege to the capital Tripoli under the pretext of ridding it of extremist Salafist militias (which are also present in the ranks of his army). After the first civil war in 2011 and the 2014 sequel, Libya was witnessing yet another armed conflict. Internal divisions had deepened even further, and the two political entities were also supported by foreign nations in terms of men and resources.

Between 2,000 and 4,000 soldiers from the Free Syrian Army came to support of the GNA in Tripoli. These troops were mainly from the Sultan Murad division, joined by Chadian mercenaries from the Fezzan. The poorly trained LNA forces were helped by a thousand mercenaries from Russia’s Wagner Group, a few hundred Syrians who had fought on behalf of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and about 3,000 Sudanese. GNA Prime Minister Serraj’s pleas for help were numerous, but they went unheeded until the intervention of a longtime partner: Turkey.

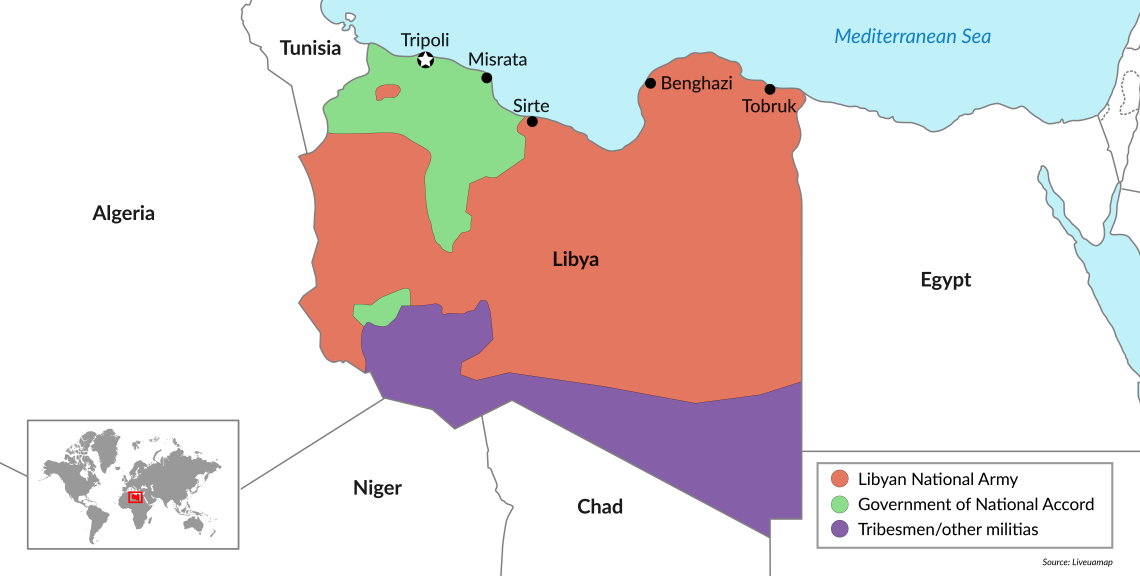

Facts & figures

Areas of control in Libya

On November 27, 2019, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed in Istanbul by the two respective foreign ministers, Mohamed Siala and Mevlut Cavusoglu, enshrining the exclusive economic zones in the Mediterranean Sea of Libya and Turkey. The signing of this agreement – though disavowed by the HoR in January 2021 – paved the way for economic and (more importantly) military cooperation between the two countries, which materialized in a second agreement. The charter sanctioned Turkey’s military intervention in Libya in support of the GNA and was ratified by the Turkish parliament on January 2, 2020.

Meanwhile, the international diplomatic process was resumed in Berlin in January 2020, but did not lead to the longed-for truce. The defeat of the LNA ultimately hinged on the overwhelming firepower of the Turkish military, which Wagner Group mercenaries were unable to counter. On October 23 of that year, a cease-fire was reached, and talk of a real peace process began. The operation sought by Mr. Haftar had resulted in hundreds of civilian deaths in Tripolitania, nearly 150,000 people fleeing Tripoli and its environs, and nearly one million citizens (out of a total of six million) in need of humanitarian assistance. Added to this were continuing blockades of oil wells and extensive damage to water and electricity infrastructure that added up to a major economic crisis.

Another unelected government

Later in 2020, in Tunisia, UNSMIL brought together representatives of the warring parties and Libyan society in a framework known as the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF). The election of a transitional cabinet was decided upon, which, after taking the place of the GNA, was to ferry the country to elections on December 24, 2021.

Members of the LPDF met in Geneva and voted for Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh as prime minister, who then formed the National Unity Government (GNU). Libya’s presidential elections, originally scheduled for December, were postponed indefinitely. The country faced increasing tensions when the HoR, opposing UNSMIL, declared the GNU invalid. It voted for a new prime minister, Fathi Bashagha, who had played a key role in defending the capital against the 2019 Haftar siege.

On March 3, Mr. Bashagha unveiled his Government of National Stability. This was a complete misnomer, since the new cabinet brought no stability. Mr. Dbeibeh did not agree to resign, and Libya took a further step backward to a country under two antagonistic governments. Meanwhile, in September 2022, UNSMIL was provided with a new special representative, the Senegalese Abdoulaye Bathily, who immediately set about organizing elections by 2023. Yet little seems to have changed.

Scenarios

In light of all these facts, the great mistake of the international community (and not only Europe) has been to count on Libyans to achieve a democratic path quickly. In the absence of functioning democratic institutions, the likelihood of a successful democratic process, seen by many merely through elections, had little chance of success. As a result of this failed electoral process, the country is as divided as ever and deeply unstable. So far, Brussels has tried to adapt to the situation on the ground.

Going forward, one scenario will see the domestic political situation stabilized, either through elections or the acceptance of the end of the term of one of the two present governments. This would allow Europe to strengthen both its political relations and economic partnerships with Libya, fostering a virtuous circle of foreign investment in the country and subsequent modernization. Unfortunately, this remains very unlikely, given the weakness of Libya’s political class and Europe’s misunderstanding of Libyan dynamics.

In a second scenario, following yet another election-related failure, nothing changes, including the relationship with Europe. This is the most likely outcome, as both politicians and militiamen have every interest in maintaining the status quo – to the detriment of democracy and any hope for national unity. Brussels, now disillusioned, will continue to cooperate locally but without any long-term strategy.