Scenarios for China’s future role in Afghanistan

With the U.S. exit from Afghanistan, China is now looking there for opportunities. Above all, it has security concerns, but also sees potential for expanding its Belt and Road Initiative. To avoid getting bogged down, it will use its ally Pakistan to influence the Taliban.

In a nutshell

- Beijing has great hopes for working with the Taliban

- It has crucial security and economic interests in the country

- China will use Pakistan to influence Afghan affairs

Even before the rapid takeover of Afghanistan, countries in the region were already making arrangements for a quick transition to Taliban rule after the United States’ planned exit. Chinese intelligence matched that of its American counterparts and others around the world: the Taliban would be in control of Afghanistan much sooner rather than later. Beijing began preparing accordingly.

In late July, China held a two-day meeting with top Taliban leaders. Along with the direct U.S.-Taliban talks held in 2018, the summit boosted the group’s international standing and signaled that large powers recognized it as a major political force on the international stage. Prior to the takeover, Taliban representatives had visited other countries, holding discussions in Moscow and Tehran. In neither of these were they personally received by the country’s foreign minister, at least not in a formal meeting.

Beijing has had many interactions with the Afghan Taliban over the years, but the Tianjin meeting – in which Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met and took photos with Taliban second-in-command Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar – was arguably the most high-profile. Foreign Minister Wang called the Taliban “a pivotal military and political force in [Afghanistan] and will play an important role in the peace, reconciliation and reconstruction process there.” Those words have effectively set the tone for China’s approach to the Taliban. Since then, the rhetoric about the group coming from various Chinese circles has been neutral or increasingly positive.

The question is whether the Taliban can meet China’s expectations.

Beijing, with a leadership most fond of realpolitik, holds great hopes for the Taliban. The question is whether Afghanistan’s new rulers will meet those expectations and how much influence China can exert on the country’s development moving forward.

China’s interests

The Taliban are an amalgam of warlord-led militias that often do not agree with each other. This means that Mullah Baradar does not speak for the Taliban as a whole. He must hold consultations (shura) with the major warlords and commanders to sell them on any political agreement he makes with China or other countries. The Taliban political office, which is responsible for external negotiations and relations, often clashes with the more extreme militia leaders.

Beijing has told the Taliban that it expects them to prevent foreign extremist groups, above all the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), from using the country to prepare, coordinate or launch attacks on China. So far, there is no sign of any such efforts. The Taliban still need the support of foreign extremist groups such as ETIM in various regions of the country.

Facts & figures

East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM)

Known in Arabic and Turkish as the Turkistan Islamic Party, ETIM is an Islamist extremist organization. Made up mostly of Uighur people and founded in western China, it wants to replace China’s autonomous region of Xinjiang with an independent state called East Turkestan. The UN lists it as a terrorist organization.

Terrorist organizations abound in Afghanistan. A United Nations report published in June 2021 found that the Taliban and al-Qaeda continue to enjoy close ties “based on ideological coherence” and formed through “common struggle and intermarriage.” The chances that the Taliban will flip on these extremist groups are slim.

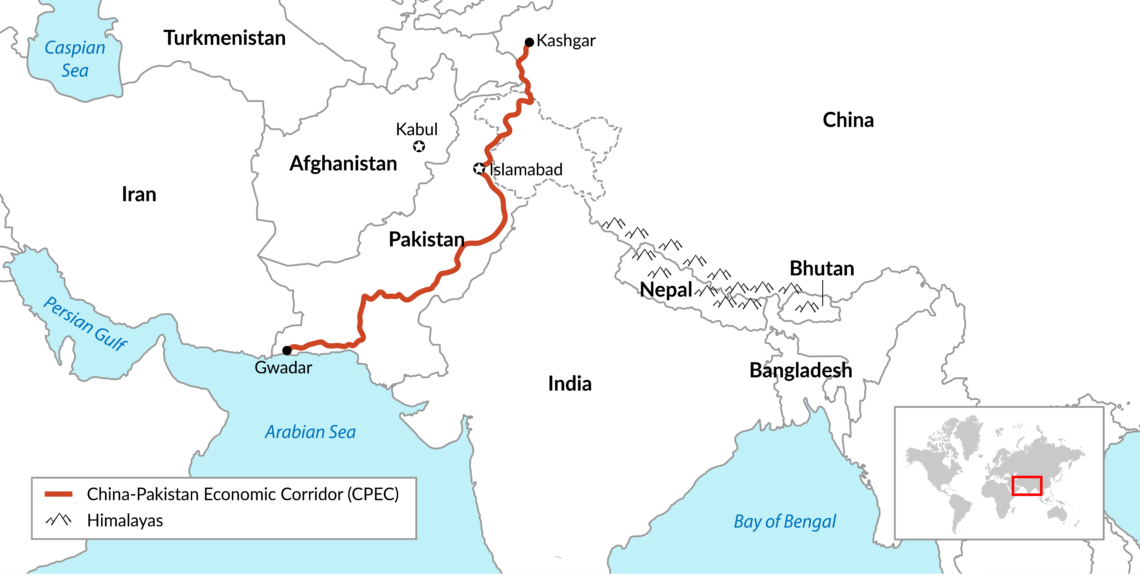

China has economic interests in Afghanistan, too. First, it wants to ensure the security of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CEPC), running from Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea to western China. Given the Taliban’s close ties to Islamabad, Beijing has well-founded hopes that the project will not be harmed. If all goes well, it might consider expanding its huge Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which the CEPC is a part, to Afghanistan in the future.

Facts & figures

China is also very interested in Afghanistan’s minerals, among them rare earth elements. And the Chinese military would be glad to get its hands on some of the fighter jets and helicopters (such as the UH-60 Black Hawk and MD-530) that are now in the Taliban’s possession.

China’s involvement

There are several ways in which China can gain influence in Afghanistan. The first is by establishing a direct bilateral relationship with the Taliban leadership; the July meeting in Tianjin was a precursor to this. What Beijing will not do is engage in conflicts in the country. Its guiding principle is to avoid any serious entanglement in Afghanistan at all costs. Chinese leaders do not want to repeat the mistakes of the British Empire, Soviet Union and United States.

China is good at piggybacking. Its economic activities in Afghanistan over the past 20 years benefited from others paying the price to keep the country relatively stable. Now, it must use its own brains and money, an approach that China’s top brass currently does not consider worth trying. Nevertheless, if the Taliban demonstrate that they meet the safety requirements for Chinese companies in mining areas, Beijing might take the risk to do business there.

Facts & figures

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

The SCO is a political, economic and security alliance founded in 2003 by China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. India and Pakistan joined in 2017. Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia are observer states.

China could use the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) to take a multilateral approach. The problem is that SCO members have disparate and sometimes divergent goals in Afghanistan. China wants to ensure security on the border of the Xinjiang autonomous region. Iran must balance its affinity for a mutual U.S. foe with the risk that close ties to the Taliban could result in further sanctions. Russia wants to prevent extremists from filtering into Central Asia. India, for its part, is worried about the potential for an Afghanistan-Pakistan-China axis to partially encircle it in the north.

Another possibility would see China and Russia join forces to deal with Afghanistan’s impact on regional instability: their interests are more aligned on security issues. In theory, both Russia and China need to fill the “security deficit” left by the West in Afghanistan. However, Moscow has greater influence in Central Asia, where states are more willing to cooperate with Russia militarily. Nor do the Russians want an active Chinese military presence in the region. Moscow-Beijing cooperation is therefore improbable, although both sides will still demonstrate a degree of solidarity when it comes to the security expectations they have for the Taliban.

China’s most likely method to influence Afghan affairs will be through pressure on Pakistan. Islamabad has close ties with the Taliban, offering the group’s members sanctuary and – allegedly – the support of its intelligence services. For years, the Taliban’s top-ranking members directed the Afghanistan insurgency from Quetta, in Pakistan’s Balochistan province.

Russia’s and China’s interests are more aligned on security issues.

The extremist Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP, also known as the Pakistani Taliban) has strong ties to the Taliban in Afghanistan. It still has about 6,000 trained fighters on the Afghan side of the border. Some anti-Chinese Uighur militant groups also have activities in Pakistan. Both the Pakistani Taliban and ETIM have publicly stated their intention to undermine the CPEC.

China already has plenty of security headaches in Pakistan, where militants often attack its projects and personnel. On July 14, 2021, a Chinese company shuttle bus plunged into a ravine after an explosion in northwest Pakistan, killing 13 people, including nine Chinese nationals. Beijing hopes that it can achieve two goals at once by pressing Pakistan to deal with the Taliban and other terrorist groups. China is willing to provide Islamabad with resources to deal with the problem because if Pakistan cooperates, it would not only benefit CPEC but could take some of the extremist pressure off of the Afghan Taliban. So far, China’s contact with the Taliban has mostly been facilitated by Pakistan.

Who are the losers?

Now that the last U.S. troops have left Afghanistan, the country could become a new battleground for competing geopolitical powers. India looks set to lose out in all this. Since the Americans invaded in 2001, India has provided more than $1 billion in stabilization funding to Afghanistan. Under the Indo-Afghan partnership agreement, New Delhi has also provided about $3 billion in development assistance, helping to build roads, dams, schools and hospitals, with more than 400 projects across all of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. The Taliban resent New Delhi’s strong support for the previous Afghan government.

Europe could see another huge influx of refugees from Afghanistan.

Certainly, the West is the biggest loser of all. The U.S. alone spent $2 trillion and lost more than 2,200 service members during its 20-year military operation in Afghanistan. Now Afghanistan is back to square one. Europe, for its part, could see another huge influx of refugees as Afghans try to escape Taliban rule.

It is still premature to call China a winner, even though it has a seemingly favorable start after the U.S. withdrawal. Many uncertainties still lie ahead, as Beijing is well aware.

Scenarios

Two possible scenarios follow. In the first, more likely scenario, the Taliban prove unable to manage a modern state. Their internal disagreements and the lack of consensus between them and extremist groups lead to significant instability in Afghanistan. In this case, China will only get involved to the extent that it will ensure its borders are protected. It will not be willing to risk investing in Afghanistan as it did when the U.S. and Western allies were stationed there – at least not in the coming three years or so.

In the second, Pakistan gets a handle on extremist groups within its borders. It pressures or influences the Taliban to manage Afghanistan in a more modern fashion, bringing the stability to the country that Beijing would like to see. Not only would China successfully complete the CPEC, it would be able to include Afghanistan in the BRI and gain access to its considerable mineral resources.