China courts Central Asia as Russia falters

The Kremlin’s obsession with conquering Ukraine has left a vacuum in Central Asia that China and Turkey are more than happy to fill.

In a nutshell

- Central Asia no longer sees Russia as a source of security or investment

- China’s greater involvement in the region is not unconditionally welcomed

- Turkey will become more involved but lacks China’s economic clout

When Moscow launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin had only just returned from Beijing, where he had enjoyed yet another friendly meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping. Determined to convince the world that the Sino-Russian relationship had never been warmer or deeper, the two expounded on their “limitless friendship.” They declared that there were “no forbidden areas of cooperation.”

To Ukraine and its friends, the atmosphere of this meeting was a significant source of concern. The fact that Beijing refused to condemn the Russian aggression was perhaps to be expected. But would President Xi take a step further and honor the friendship by providing military support? A determined Chinese effort to shore up the flagging Russian war effort could have made a big difference.

Recent developments have put such fears to rest. Despite alarmist voices in the West and Russian pleas for more help from Beijing, there has been no solid evidence of extensive Chinese military support. That suggests that the true nature of the Sino-Russian relationship is fundamentally different from the popular perceptions.

An unequal relationship

The professed friendship between the two countries has long been a source of conceptual confusion. To some, the optics have been convincing indeed. The mutual praise, with the two presidents repeatedly referring to each other as “dear friend” was hard to miss, and bilateral trade has been rising in tandem. While Beijing and Moscow have a mutual interest in standing up to the United States and improving their economies, the essence of the friendship remains what veteran China analyst Bobo Lo described in the 2008 book “Axis of Convenience: Moscow, Beijing and the New Geopolitics.”

As the war in Ukraine drags on, the relationship is becoming increasingly skewed in favor of China, with Beijing pouncing on every opportunity to help itself to Russian resources while providing little in return. The pattern has long favored the Middle Kingdom, which has imported weapons and hydrocarbons while finding a market to export cheap manufactured goods. This dynamic supports Chinese producers while cementing the role of Russia as a resource-based economy that is weakly represented in global value chains.

Although Russia did expect to gain from the rollout of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), there has been little Chinese direct investment. The promise of Chinese participation in building a high-speed railway between Moscow and Kazan came to nothing. Following the spotty performance of Russian weapons in Ukraine, Beijing has reason to doubt the quality of the weapons technology it has received from Russia.

Also by Stefan Hedlund

Central Asia is coming into its own

Xi’s March visit was a bust for Moscow

When President Xi prepared for his visit to Moscow on March 20, there was concern that Beijing might have finally decided to throw its weight behind Russia. It was ominous that Belarusian strongman Alexander Lukashenko, one of the few remaining allies of Russia, was received in Beijing only days before. Many also noted that when President Xi arrived in Moscow, he and his Russian counterpart had met more than 40 times, starting with Mr. Xi’s first visit to Moscow as president in 2013.

For the Kremlin, however, the outcome of the latest visit was a huge disappointment. Ukraine and Chinese support of Russia was not mentioned publicly. Yet President Xi came away with a slew of contracts that likely ranged from Russia transferring additional weapons technology and selling hydrocarbons at low prices to an agreement that mutual trade will be conducted in Chinese yuan, a bid to weaken the global dominance of the U.S. dollar.

An awkward development highlighted the already vast difference in standing between the two leaders: the meeting took place only days after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for President Putin on charges of having illegally abducted children from Kremlin-occupied parts of Ukraine. The implication is that there are now few countries that the Russian president will dare to visit for fear of being arrested and sent to The Hague.

Facts & figures

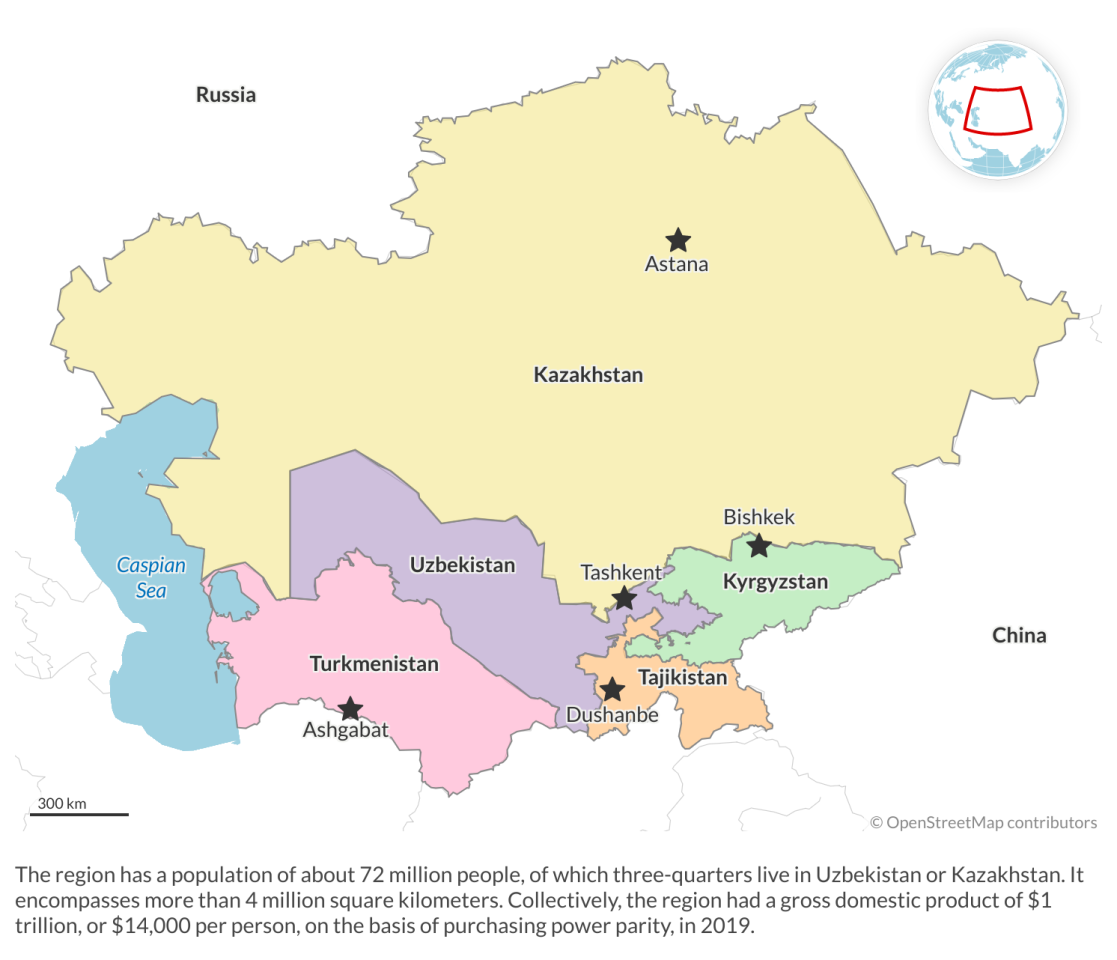

China will host the China-Central Asia Summit on May 18

Adding insult to injury, President Xi left Moscow and wasted no time inviting the five Central Asian countries to take part in a China-Central Asia Summit on May 18 without Russia. This effrontery may be considered the end of the Kremlin’s much-touted pivot to Asia. Launched at the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Vladivostok, President Putin’s ambition was that a turn to the east would allow the Russian economy to “catch the Chinese wind” in its sails. Rather than picking up speed, the Russian ship may be listing a bit now but still sailing.

It is unclear what dissuaded China from honoring its “limitless friendship” with Russia. While American threats of economic sanctions could have played a role, a more powerful motivation is probably Beijing’s desire to develop markets in Europe and drive a political wedge between the European Union and the U.S. In early April, Beijing allowed its ambassador to the EU, Fu Cong, to dismiss the “limitless friendship” as “nothing but rhetoric.” The subsequent visit to Beijing by French President Emmanuel Macron may have given Mr. Xi hope that such a charm offensive would work.

Central Asia no longer sees Russia as a protector

Closer to home, the implosion of Russia as a great power has wide-ranging implications for Central Asia. It has long been assumed that there is an implicit separation of roles between Moscow and Beijing – Russia provides security while China delivers investment and business development. If that compact ever existed, it no longer does now. Russia’s armed intervention to restore domestic order in Kazakhstan in early 2022 may have been its last stand in the region. Proposed joint drills with other countries have been canceled. Given the strain on the Russian economy, its ability to play a significant role in future trade and development in Central Asia is doubtful. The main question for Beijing is how much it will capitalize on the Russian vanishing act.

From Beijing’s standpoint, the numbers are encouraging. At the end of 2020, total Chinese investment in Central Asia had reached about $40 billion, more than half in Kazakhstan alone. At the end of 2021, close to 8,000 Chinese firms were operating in the region, and by the end of 2022, Chinese trade with Central Asia had reached $70 billion, up by 40 percent over the preceding year.

The ambitions for the future are correspondingly high. Appearing at the APEC summit in Bangkok in November 2022, President Xi announced that China would consider hosting a Third Belt and Road International Cooperation Forum in 2023, aiming to provide new impetus for development in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond.

Beijing’s ‘grandiose plan’ for Central Asia

In connection with the upcoming China-Central Asia Summit, to be held in the Shaanxi Province capital of Xian, it was also announced that Beijing is preparing a “grandiose plan” for its relations with countries in the region.

It is likely to have three main features. First and foremost is the Chinese need to boost piped natural gas imports to curb its rapidly increasing dependence on liquefied natural gas. Despite much talk about Russian gas being redirected from Europe toward the Asia-Pacific, the Power of Siberia, inaugurated in 2019, remains the only available pipeline for export to China. It will not be at full capacity until 2027. Talks on the Power of Siberia II gas route remain stalled and would take years to complete.

The likely outcome of China’s grandiose scenario for Central Asia is a sort of halfway house of partial successes marred by obstacles and reversals.

Beijing hopes, instead, to add a fourth line (“Line D”) to its Central Asia-China gas pipeline network. It would tap further into the vast reserves in Turkmenistan, which already accounts for 75 percent of Chinese gas imports from the region. The downside is a combination of regional energy shortages and production disturbances that have caused repeated disruptions in gas flows. The governments in both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are conscious of the risks involved in maintaining flows to China when gas is in short supply at home.

The second feature of the “grandiose” scenario is a need to reinvigorate the BRI, which has stalled in recent years. The problem is that the northern spur expected to proceed via Russia is dead for the foreseeable future. That leaves the southern spur, which crosses the Caspian Sea. It will require cooperation with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in upgrading infrastructure and with Azerbaijan and Turkey. Above all, it will need to ensure that European markets remain open for an expansion of Chinese imports.

Broad-based investment in greater production, including equity stakes, is the third and most challenging feature. Reaching this goal requires more than capital and good government connections. Industrial development hinges on horizontal business networks that, in turn, require the foundation of trust. Yet popular sentiment has, in recent years, been turning against China.

Scenarios

The likely outcome of China’s grandiose scenario for Central Asia is a sort of halfway house of partial successes marred by obstacles and reversals.

The promise of massive foreign direct investment will be a sweetener, especially given the unlikelihood of serious investment from Russia. Demography will help, as the older generation of people who received Russian education and were cultivated into Russian networks is being replaced by a younger, more nationalistic generation. The proliferation of Confucius Institutes will advance the appreciation of Chinese culture and proficiency in Mandarin.

The downside is that regional governments have been burnt by Chinese debt trap diplomacy, which Beijing exploits to extract concessions, ranging from equity stakes to actual land grabs. Chinese repression against the Muslim Uighur population in Xinjiang has hurt Beijing’s standing among the emerging younger generation of Muslim nationalistic Central Asians. If Beijing seeks military bases in the region, it will add further resentment.

More recently, the Chinese ambassador to France’s comments questioning the sovereignty of the 15 former Soviet republics are not likely to be forgotten, despite Beijing’s quick disavowal of Lu Shaye’s remarks. Polls have shown that many in Central Asia remain wary despite China’s massive investment.

A parallel scenario is that Turkey realizes its long-standing ambition of promoting a pan-Turkish agenda of trade and security cooperation across the region, where four of the five states are Turkic-speaking. The upside of this scenario is that the war in Ukraine has caused regional governments to grow weary of Russia. The recent pattern of warming relations between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan suggests they may be getting ready to look elsewhere for military cooperation.

Ankara actively promoted military-industrial cooperation before the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, and its support for the Ukrainian side – notably but not exclusively Bayraktar attack drones – has been helpful in marketing elsewhere. Chinese efforts to breathe new life into the BRI will also be helpful to both Azerbaijan and Turkey.

As Russia is being phased out of Central Asia, Turkey and China will become the most active players. In such a competition, the brute strength of the Chinese economy will give Beijing an edge that Ankara’s economy cannot match.