The geopolitics of CPTPP enlargement

Three new applications to a Pacific-region trade deal are posing complex strategic choices and include a proxy battle between Washington and Beijing.

In a nutshell

- China, Taiwan and the UK are angling for the CPTPP

- Their prospects will hinge on geopolitical tensions

- The British application may have the best chance

As global trade is increasingly determined by geopolitical dynamics, the accession negotiations at the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) serve as a salient case in point.

At stake are three new applications for entry into the 11-member group, by the United Kingdom, China and Taiwan. The UK’s candidacy alters the geographic focus of what has so far been an exercise in Asia-Pacific trade liberalization. Meanwhile, the efforts by China and Taiwan represent a proxy battle: between the United States-led global order and its 75-year-old alliance system, and Beijing’s geostrategic ambitions, underpinned by the Belt and Road Initiative.

For China, applying for CPTPP membership is shrewd geoeconomics – a potential win-win but one that carries big risks. Its own success is less important to Beijing than whether Taiwan accedes. Unlike when the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum was founded in 1989, it is hard to imagine the China of today being in the same trade bloc with Taiwan, which Beijing considers a “renegade province” from the Chinese civil war that culminated with the communist revolution in 1949.

At the same time, Taiwan’s accession to the CPTPP without the same for China would be a major strategic blow for Beijing. It would fundamentally negate its “One China” policy, undermine its global standing and prestige, embolden Taiwan’s pro-independence movement, and deepen the global divide between China and the U.S.

Strategic context

For its part, the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden has been stepping up its support for Taiwan in the face of Chinese intimidation to forcefully unify the democratic and prosperous island state with mainland China. While the trade grouping has long been politicized, the CPTPP will now likely become an arena of geopolitical contest. China’s overall strategy appears to be twofold: trying to gain accession for itself, and to prevent Taiwan from doing the same. If it somehow gets to join first, after a long process of deliberation chaired by Singapore this year and by New Zealand in 2023, Beijing can use its membership to prevent Taiwan’s entry.

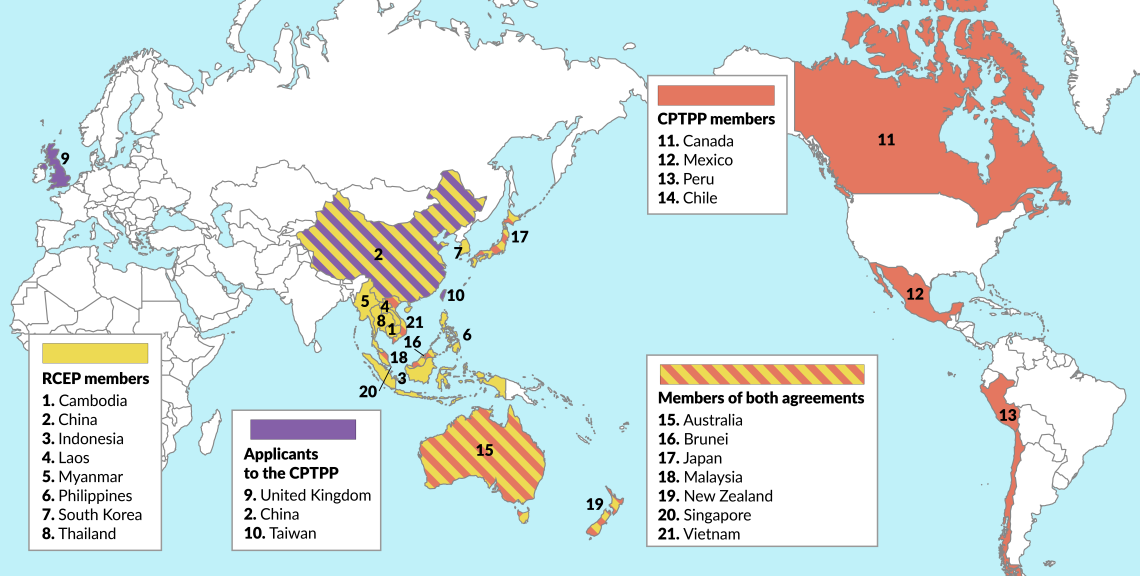

To be sure, the CPTPP membership – Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam – has come a long way from its origins two decades ago as a trade partnership among four small economies. That initial group (Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore) later joined what became the Trans-Pacific Partnership under former U.S. President Barack Obama’s leadership, incorporating traditional American allies and leading trade partners including Australia, Canada, Japan and Mexico.

The prospect of a U.S. return to the trade deal under the Biden administration now seems remote.

While it was a pillar of Mr. Obama’s geo-economic strategy, complementing the so-called “pivot and rebalance” to Asia, TPP also became an alternative “gold standard” of trade liberalization, in view of the World Trade Organization’s failed Doha Round. It served as a kind of second-best solution for the demise of the multilateral trading system. As is well known, former U.S. President Donald Trump promptly delivered on a promise to domestic voters opposed to globalization and liberalization by pulling the TPP’s biggest economy out in 2017.

Thanks to Japan’s leadership under the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, what was left of the TPP was salvaged and became the CPTPP. The prospect of a U.S. return under the Biden administration now seems remote. Protectionist and anti-globalization sentiments remain strong currents in the stream of American public opinion. Rather than rejoining the CPTPP, the Biden team appears more interested in a new trade policy direction – perhaps complementing its strategy to galvanize global democracies to stand up and be counted, as evidenced in the recent “summit for democracies.”

Trade environment

Washington is therefore excluded from the two main and overlapping trade blocs that have emerged in the past half-decade, the CPTPP and the 15-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). While China is applying to join the former, it is a founding and largest member of the RCEP, which is centered around ASEAN alongside Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. India opted out at the last moment, owing to domestic vested interests and its rationalization of already having bilateral free-trade agreements with most RCEP economies.

RCEP represents more of a streamlined, “freer-trade” architecture between ASEAN and its major dialogue partners, instead of full-fledged trade liberalization in the mode of the WTO. RCEP pools together 30 percent of global trade and gross domestic product, with 40 percent of the world’s population. While the CPTPP is smaller – with 15 percent of global trade and 13 percent of global GDP, and just 6 percent of the world population as its market – the 11-member trade liberalization platform is more comprehensive and substantial.

The CPTPP includes chapters on labor and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), freedom of association and elimination of forced labor, and digital requirements, as well as a prohibition on the forced disclosure of source code. These rigorous, behind-border liberalization policies extend well beyond RCEP’s scope. CPTPP’s membership, led by trade policy experts from Japan, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, is also tighter, with much greater potential for complementarity and efficiency gains.

Among ASEAN economies, Brunei and Singapore were two of the original four; but it was a coup of sorts for Malaysia and Vietnam to get their domestic acts together and join. Thailand missed out completely due to its domestic conflict and consequent policy inertia, and it is unlikely to have its house in order enough to sign on to the CPTPP for the foreseeable future. This means that Vietnam, and to a lesser extent Malaysia, are likely to make international trade and foreign investment gains at Thailand’s expense.

Deeper agendas

In view of this regional trade environment, China’s CPTPP application does not on its face seem sensible. China has locked horns with Australia in an ongoing trade and tariff war. It began with Canberra’s accusation of Chinese culpability for the Covid-19 pandemic, prompting Beijing’s pushback with bullying tactics and harsh diplomatic responses – sometimes known as “wolf warrior diplomacy.” Unsurprisingly, the Australian government under Prime Minister Scott Morrison is unenthusiastic about Beijing’s interest in the CPTPP. Japan is similarly cool on the idea, owing to long-standing tensions with China. Vietnam is in the same boat, facing a range of sovereignty issues with China in the South China Sea on top of historical grievances.

Viewed in this light, China is clearly posturing. First, it wants to display global leadership by applying itself where the U.S. has quit. As Washington turns its back on multilateral trade liberalization, Beijing hopes to be seen as a promoter of free trade. Even if its bid fails, the benefit of being an ostensible supporter of trade liberalization will have been gained.

China’s move is aimed at staying out in front on trade as external pressure builds on geopolitics.

China’s apparent duplicity lies in the CPTPP’s provisions on the role of SOEs – a huge sector in the Chinese economy, which would face unprecedented competition if liberalized. China’s similarly protected labor practices, and its lack of labor rights, digital requirements or freedom of association, further show that Beijing is probably aware that accession based on merit may be doomed from the start. China is so authoritarian in its economic management that joining the CPTPP seems antithetical and illogical.

China’s CPTPP application is also likely designed to split the grouping. Some will oppose, whereas others will be supportive. Opposing Australia, Canada, Japan and Vietnam, in the skeptical camp, China may want to leverage its deepening economic ties with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) for CPTPP gains. Established in July 2014 under the leadership of Xi Jinping, the intergovernmental China-CELAC Forum includes Chile, Mexico and Peru. These three Latin American economies and CPTPP members are increasingly reliant on China for trade and investment. Beijing’s lobbying to get into the CPTPP is likely to rely on these three CELAC members.

Third, China may be making a geo-economic move in the face of geopolitical pressure. Although its official CPTPP bid taking place one day after the formation of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) trilateral security pact may seem coincidental, China’s move is aimed at staying out in front on trade as external pressure builds on geopolitics.

Here, again, is Beijing’s apparent aim to claim the “high ground” of multilateral and plurilateral trade liberalization just as its adversaries are ganging up on it. As a result of the China-Taiwan dynamics, the UK’s application appears more autonomous and straightforward, reflecting the country’s imperative to find its own way after leaving the European Union.

Scenarios

Accordingly, the leading scenario is that the UK may end up as a beneficiary of the China-Taiwan competition to join the CPTPP. The prospect of accepting China but not Taiwan is unlikely to appeal to the pro-democracy and anti-China camp among the 11 member economies. Moreover, as they already have bilateral free-trade agreements with Taipei, New Zealand and Singapore are likely to view Taiwan’s entry more favorably. Yet taking in Taiwan without China is also unpalatable, because of the geopolitical tensions that such a decision would stoke. The pro-China Latin American countries are also unlikely to allow Taiwanese but not mainland Chinese accession.

The second scenario is for the CPTPP’s pro-democracy members, led by Australia and Japan, to accept Taiwan, with or without the UK, but exclude China. Leaving China out while letting Taiwan in would be earthshaking – sending an unmistakable message to authoritarian leaders in Beijing. The least likely scenario is for China to be admitted, with or without both the UK and Taiwan, reflecting trade dynamics and the reality of China’s locomotive role in Asia-Pacific’s trade and investment.

On purely geostrategic grounds, the first scenario is the most likely. China and Taiwan would seem to cancel each other out – unless both are accepted into the CPTPP. The UK’s CPTPP prospects may be more promising, because the bloc of 11 may not want to come out of this enlargement phase looking exclusionary and closed. To stay open on trade liberalization, the current CPTPP group will come under pressure to admit at least one applicant, if not all three. South Korea’s recent interest to accede would not alter this logic.

Letting the UK into the CPTPP would allow members to claim that liberalization can still be multilateral, while staying out of unfinished business between China and Taiwan