China’s evolving economic footprint in Latin America

Beijing is the top trade partner for nine Latin American nations. But China’s recent economic slowdown has reduced its greenfield investments and sovereign lending in the region.

In a nutshell

- The position of the United States slipped gradually due to negligence

- Some Latin American nations are, however, dissatisfied with China’s terms

- China is unlikely to surpass America because of proximity and historical ties

For more than a century, the United States has been the undisputed economic hegemon in Latin America. However, over the past two decades, China has displaced the U.S. as the region’s top trading partner in many Latin American nations. Additionally, Beijing has become a major source of foreign direct investment and lending. Increasingly, Latin American governments of all ideological stripes view China as a viable economic alternative.

These developments and an unfocused U.S. response suggest that Latin America’s medium-term economic future may well be marked by dual U.S.-Chinese dominance, a scenario that may benefit the region.

Chinese economic interests in Latin America

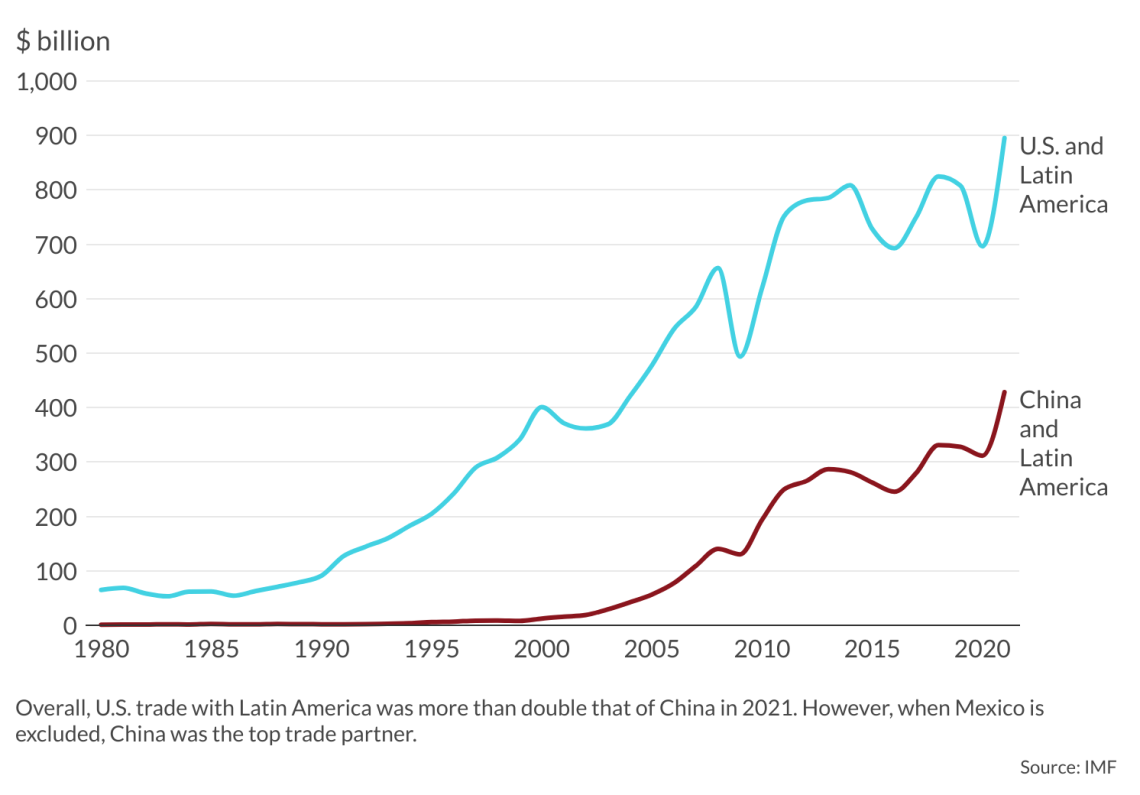

China’s economic ascension in Latin America was driven by its interest in securing resources during the commodities boom of the 2000s and early 2010s, investment of its growing wealth and global geopolitical ambitions. Chinese trade with Latin America grew from just $12 billion in 2000 to more than $430 billion in 2021, driven by demand for a range of commodities, from soybeans to copper, iron ore, petroleum and other raw materials. These imports, meanwhile, were tied to an increase in Chinese exports of value-added manufactured goods. As of 2022, China is the region’s second-largest trading partner and the biggest trading partner in nine countries (Cuba, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Uruguay, Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela).

When Mexico is factored in, however, the U.S. trade figures were more than double those of China in 2021 – $895 million compared to $428 million, according to the International Monetary Fund. Mexico accounts for 71 percent of America’s Latin American trade.

Economic linkages between the two regions are not restricted to trade. With its deep pockets, China has extended more than $140 billion in sovereign loans since 2005 to Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela and others, often in exchange for oil (although as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic it offered no new loans in 2020 or 2021). China has also prioritized foreign direct investment through its global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), sending billions to Chinese and Latin American companies through the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. These companies have invested in regional infrastructure projects, including bridges, port facilities, hydroelectric dams and highways. In Latin America, 11 countries – Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Cuba – have signed onto the BRI.

China’s growing economic ties with Latin America represent just one of the many steps it is taking to pursue its global ambitions.

As the BRI suggests, Chinese economic engagement is not merely about gaining access to natural resources and new markets, but geoeconomics. As political economist Albert O. Hirschman postulated in 1945, increased trade and trade dependence between states tend to produce geopolitical bonds and even foreign policy convergence. In this sense, China’s growing economic ties with Latin America represent just one of the many steps it is taking to pursue its global ambitions. Concretely, it may also be part of a gambit to diplomatically isolate Taiwan: about half the countries globally that still recognize Taiwan as an independent nation are located in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Latin America’s pivot

For their part, Latin American governments have welcomed the ascent of China. During the 2000s and early 2010s, it was left-of-center governments in places like Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, and Ecuador that were most receptive to Chinese investment and loans, in part because they sought to distance themselves from the U.S. and Western financial institutions for ideological reasons.

However, this is no longer necessarily the case, as right-of-center governments increasingly view China as a pragmatic economic alternative to the U.S. To wit, in recent years, Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru have signed bilateral free trade agreements with China, and governments of diverse political makeups in Ecuador, Uruguay, Panama, Colombia and Nicaragua are all in the process of negotiating similar deals.

Part of the reason for this change is U.S. negligence. Among the factors damaging Washington’s reliability and reputation are the breakdown in support for free trade among both Democratic and Republican parties, the U.S.’s 2017 withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Trump administration’s repeated threats of using punitive tariffs as a political tool. China has been eager to fill the void for Latin American governments seeking alternative trade partners. Academic studies, for instance, support the notion that China has strengthened its ties with those countries where the U.S. influence was weakest.

Many Latin American countries are no longer bound to a single economic power and can bargain among several partners. For example, in exchange for joining the BRI in early 2022, Argentina received billions of dollars in Chinese currency swaps and financing, allowing it to make some short-term debt payments to the International Monetary Fund.

So far, the U.S. response to China’s ascendence has been more reactive than proactive.

Conversely, Latin American politicians may be lured back to the U.S. by what they perceive to be predatory loans from Beijing, Chinese indifference to the environment and human rights and the need to retain control over land and strategic minerals like lithium. This may ultimately result in better borrowing conditions for Latin America, as states compare the transparency, quality and productivity of Chinese-funded projects versus U.S.-funded ones.

Facts & figures

The U.S. reaction

So far, the U.S. response to China’s ascendence has been more reactive than proactive. Domestic U.S. public opinion is less sanguine about free trade than it once was, and although the U.S. enjoys free trade agreements with 11 Latin American countries – Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and Peru – it is not currently in new negotiations with any others in the region.

Instead, Washington has tried to block specific Chinese infrastructure and technology projects in Latin America. Chief among these is Huawei, which the U.S. has been trying to shut out on security grounds since 2012, with limited success. One of the top targets is Huawei. The U.S. pushed Chile to nix a plan for the Chinese tech giant to build a trans-Pacific undersea cable to connect Valparaiso and Shanghai. It struck a deal with Ecuador conditional on the exclusion of Chinese telecom companies. Nonetheless, this is the exception rather than the rule. Most Latin American countries continue to seek Chinese technology investments and are proceeding with Huawei as a potential or confirmed choice for their 5G wireless networks.

America has been more engaged through FDI, which rose sharply in 2021. Pandemic disruptions to the global supply chain have provided an impetus for nearshoring opportunities which would directly benefit Latin America. This is more than a passing interest for the U.S.: in 2021, President Joe Biden issued an executive order calling on U.S. government agencies to address risks to supply chains and encouraged U.S. firms to bring production closer to home. The countries most poised to take advantage of this are Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean – especially those which are politically stable democracies. Not coincidentally, the share of Mexico’s exports to the U.S. versus Asian exports increased from 37 percent in 2018 to 41 percent in 2021 and 44 percent in 2022.

Scenarios

There are three realistic trajectories for the evolution of Latin American economic engagement with China and the U.S. In order of likelihood, these are: 1) Chinese and U.S. coexistence, 2) U.S. dominance, and 3) Chinese ascendence and hegemony.

Dual hegemons

By far the most likely outcome is one in which China and the U.S. coexist as hegemons, competing for a share of Latin America’s economic pie. As described at length above, China has now established itself as a major power in the region, while the U.S. retains its own entrenched economic interests. Each country has forged a series of bilateral free trade agreements across Latin America, and both China and the U.S. retain a sizable financial presence in the region through FDI and lending. In this scenario, China is most likely to expand its presence in authoritarian countries (Venezuela, Nicaragua, perhaps El Salvador or Guatemala) and in South America, while the U.S. continues to hold sway over Mexico and the rest of Central America and the Caribbean in a continuation of the historical attention it has paid to this part of its “neighborhood.”

The U.S. reclaims dominance

The second most likely scenario is for the U.S. to reclaim its economic dominance in the hemisphere. Its ability to do so would be assisted by four things: 1) geographical proximity, which is immutable, 2) cultural ties, 3) economic distancing between Latin America and China as each becomes more familiar with the other, and 4) U.S. economic reengagement.

To begin, due to geographical proximity, it makes economic sense for the U.S. to seek primary products – especially agricultural goods but also manufactured items – from Latin America rather than other regions. Geography is one factor that helped spur the U.S.’s long history of investment in the region, especially in Mexico and the Caribbean basin. Indeed, existing free trade agreements with Mexico, Central American states, and the Dominican Republic are testaments to those relationships.

Second, the U.S. and Latin America share deep-seated cultural linkages that do not exist historically between China and the region. Among other things, English is the third-most spoken language in Latin America after Spanish and Portuguese, and English-language television, movies and music are pervasive in Latin American culture. In the U.S., Spanish is the second-most spoken language and Spanish-language media is increasingly prevalent. Additionally, there is a history of more than a century of Latin American immigration to the U.S., which creates additional economic bonds.

Third, Latin American states or China may seek to distance themselves from one another. As noted above, some Latin American politicians have discovered that Chinese loans and economic assistance are often more rapacious than those offered by Western financial institutions. Although China has been willing to renegotiate the terms of loans in some places such as Ecuador, leaders are increasingly voicing concerns about neo-dependency. Grassroots opposition to Chinese infrastructure projects has also grown across the region.

Conversely, given the risks associated with loans to risky countries like Venezuela and Argentina, China may wish to step back from Latin America. Beijing is already beginning to place a greater emphasis on more reliable investments amidst slowing economic growth.

Lastly, the U.S. may seek economic re-engagement, including the revival of discussions for a hemispheric trade bloc, expanding guest worker programs, and promoting nearshoring. The reason this scenario seems less likely than Chinese-U.S. coexistence is because of the lack of urgency in the U.S. regarding Latin America and increasing global economic ties. The hemispheric trade bloc proposal remains dormant while expanded guest worker programs face intense political difficulties in the current U.S. political climate.

China surpasses the U.S.

It is also possible, though not likely, that the U.S. fails to make Latin America a priority, pursues a protectionist economic policy, and allows China to make further inroads in the Caribbean and Mexico without much resistance. Supporting this idea, trade between China and Latin America will continue to grow over the next decade, and China remains in a place where it can comfortably make economic and diplomatic investments in the region.

Meanwhile, contentious U.S. domestic politics and shortsighted foreign policy may leave the door open for China. However, this seems to be the least likely outcome. Among other things, it is impossible to change geography and difficult to break regional cultural affinities – even if the U.S. fails to prioritize its relationship with Latin America. Moreover, Chinese greenfield investments and sovereign lending have decreased significantly in recent years as the Chinese domestic economy has slowed and investors have faced uncertain returns for their investments.