The strategic implications of China’s Arctic Road

China has proposed building a link to Western Europe through the Arctic as part of its huge Belt and Road Initiative. Beijing insists its intentions are purely economic and scientific, but such a pathway dominated by China would tip the strategic balance in the region.

In a nutshell

- China has proposed creating an Arctic link to Europe

- Doing so would increase its influence in the region

- That could tip the strategic balance, with consequences for Russia and NATO

- Western opposition is likely to grow, though without a coordinated response

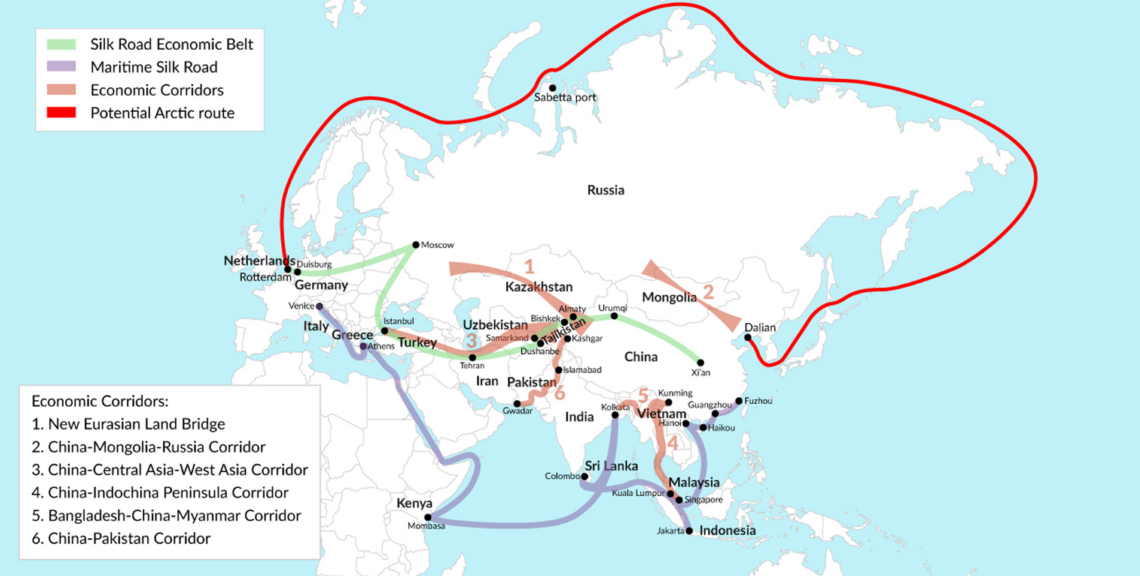

In 2017, the Chinese government released a document entitled “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative.” It included an idea for an Arctic link between China and Western Europe, complementing its other plans to construct infrastructure and trade routes connecting the country with Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

China’s ambitions were further developed in a white paper released in January 2018, which emphasized the importance of economic and scientific development in its Arctic strategy. While there is widespread interest in Chinese investments in infrastructure, there are also growing concerns over Beijing’s strategic intent, as well as skepticism over whether the plans will be realized and deliver significant economic and strategic benefits to China or others. Nevertheless, Arctic nations are accounting for China’s policy in their own schemes for future developments in the region.

The addition of a great northern route to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has prompted several assessments about Beijing’s intentions and its prospects for successfully developing a China-dominated Arctic pathway. For instance, Heather Conley recently authored a report on the subject for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an influential Washington-based think tank. The report concludes that China, which now describes itself as a “near-Arctic power,” will make positive contributions to the development of the region. Among the positive influences she cites are Chinese investments in the region in partnership with at least six countries, including the United States. In 2017, for example, China signed an agreement to invest in Alaskan LNG production.

Growing apprehension

On the other hand, others worry that China’s influence is not benign. As with the development of other routes in the BRI, concerns include the possibility of “debt traps,” as when Sri Lanka had to turn control of strategic ports over to Chinese state-owned companies after accumulating over $1 billion in debt. Other fears include growing Chinese political influence and strategic encroachment. Last year, for example, the Danish government repurchased a shuttered military base in Greenland that had been sold to a private buyer, out of fear that the Chinese government might try to buy the facility.

Beijing’s demand for a more prominent role in Arctic governance has unsettled nations in the region.

Beijing’s demand for a more prominent role in Arctic governance has unsettled nations in the region. Polar cooperation has largely been directed through the Arctic Council. So far, the organization, which does not deal with security issues, has managed to balance the interests of its members. Notably, acrimony with Russia over issues like Ukraine and Syria has not hurt Arctic cooperation. A more assertive China introduces a new and potentially destabilizing dynamic. China has observer status at the council.

Currently, there is too little activity to evaluate the impact of an “Arctic Silk Road” or China’s true long-term intentions. In 2016, for example, there were only 19 commercial polar crossings. That same year, more than 75,000 commercial vessels transited the Strait of Malacca.

Nevertheless, the prospects for economic development in the Arctic are growing. Finland and Norway, for example, are considering building an Arctic railway between Norway’s ice-free port at Kirkenes and the city of Rovaniemi in Finland. The railway could link to north-south development projects under the Three Seas Initiative (a forum of countries between the Adriatic, Black and Baltic Seas), creating a new corridor for energy, economic development and trade through Central Europe. This corridor could well link to a hub on China’s Arctic route.

The U.S., Canada and the Nordic nations have responded to the potential of Chinese development in the Arctic with a mixture of openness to investment and caution against offering Beijing undue strategic leverage. Even Russia, which has also partnered with China on Arctic projects, has shown unease about seeing its dominance as a polar power leveraged or eclipsed by the Chinese.

Western response

The West has offered no coherent response to the Chinese investments in polar regions and Beijing’s demand to play a larger role in Arctic governance. Yet, there are signs of change. Anxieties about China’s ambitions will likely be fueled by worries about its destabilizing impact on the global order.

The most significant element is shifting attitudes toward China in Western Europe. Even as Beijing seeks to expand commercial ties and investments, governments are increasingly wary of Chinese influence. This is partly reflected by Europe’s growing interest in instituting processes similar to those used by the Committee on Foreign Investments in the U.S. (CFIUS). Nordic governments are becoming the most skeptical about China. Even European Union representatives, in conversations, press for more transatlantic deliberations and assessments of China’s long-term goals. In contrast, the United Kingdom stands alone among major European powers in its reluctance to let go of the presumption that China’s rise will be a benign influence on the continent.

Canada, a major Arctic power, takes its role and influence in the region seriously. However, it has yet to demonstrate any significant concern over Chinese polar activity. Canada claims sovereignty over proposed shipping routes mentioned in Beijing’s 2018 white paper.

The role the U.S. will play is pivotal, but unclear. Last year, Washington completed its term as the chair of the Arctic Council. U.S. leadership at the time was indecisive. The Obama administration seemed a bit out of step with the Nordic countries, which were more interested in sustainable development. The new U.S. administration has so far not established a clear direction for its Arctic policy.

It is unlikely we will see a decisive U.S. response to China’s Arctic pathway proposal anytime soon.

It did recently complete an Indo-Pacific framework that addresses the Belt and Road Initiative overall. However, there is a lot on the administration’s plate at the moment. Significant changes in the national security team have recently been made, while several near-term priorities will demand the National Security Council’s attention: a decision on the Iran deal, a meeting between President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, and the July NATO summit. It is unlikely we will see a decisive U.S. response to China’s Arctic pathway proposal anytime soon.

Scenarios

In the near term, the most likely scenario is that the West will fail to make a coordinated response to China’s Polar Silk Road. The U.S. will not provide decisive leadership, nor will other Arctic nations fully reconcile their desire for Chinese commercial investments and their national security concerns. On the other hand, China is unlikely to make significant inroads by playing a more prominent role in the Arctic Council or influencing the behavior of the Nordic states, Iceland, Russia, Canada or Greenland. Still, there will likely be some piecemeal efforts foreshadowing a more structured national security response, including the expansion of CFIUS-like processes in Europe.

The U.S. will likely revamp its Unified Command Plan, shifting primary coordinating responsibility to the U.S. European Command (EUCOM) to better harmonize Arctic security policies with NATO allies. Canada will undoubtedly continue to object to NATO addressing the Arctic as a security issue. Worries about growing Chinese influence, however, may well overcome those objections. Moreover, the U.S. will probably add more civilian and military infrastructure in the Arctic. Expect the U.S. to expand its fleet to include six icebreakers and field the Arctic-capable National Security Cutter.