A patchwork response to China’s latest push

Tensions have flared in the South China Sea, especially between China and the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia. The three latter countries, however, have very different relationships with Beijing. China can use this divide the region to gain greater control over the region.

In a nutshell

- A souring relationship with the U.S. will weaken Manila’s hand

- Vietnam will try to paper over differences with Beijing

- Indonesia will stand its ground against Chinese assertiveness

The past year has created tensions on the South China Sea geopolitical scene. There were several major developments involving China and countries bordering the sea, particularly the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia.

These developments appear serious, capable of overturning attitudes in the region and changing Southeast Asia’s general passivity toward Chinese aggressiveness. However, the nature of these countries’ relationships with China and differences in their approaches make a concerted and effective response to Chinese designs unlikely. More likely is a mix of approaches which, taken together, will not be enough to frustrate Chinese efforts to establish effective control over most of the South China Sea.

The Philippines

The biggest development in the Philippines’ national security policy and one which will have a direct impact on its posture in the South China Sea is President Rodrigo Duterte’s formal termination of the 1999 Philippines-United States Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA). If the Philippines follows through on ending the VFA – and there is no guarantee that it will – the country would lose a crucial card in its already weak hand.

The Philippines simply does not have a meaningful enough presence in the South China Sea to challenge Chinese encroachments. To enforce its claims, its navy has three refurbished American coast guard cutters and several smaller craft of various origin. It also has its own small coast guard. Both services are equipped with a few aircraft. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Philippines would “struggle to provide more than a token national capability to defend its maritime claims.”

The Philippines does not even have the capacity to fully monitor the activity of other countries’ forces in the areas it claims.

In fact, the Philippines does not even have the capacity to fully monitor the activity of other countries’ forces in the areas it claims. Cooperation with the U.S. has helped fill this surveillance gap. If it proceeds, over time U.S. assistance (and that of its allies, like Australia) will help the Philippines develop more robust capabilities. The U.S. naval presence has also helped provide a credible deterrent to the most aggressive of Chinese moves in Philippine-claimed waters.

The Chinese have continued to press their claims vigorously, despite U.S.-Philippine cooperation. China remains in control of the disputed Scarborough Shoal, which it seized in 2012 (though it usually permits Filipino fishermen to access it) and has intensified activity elsewhere in the area of the Philippines’ claims. Over the last year, Chinese maritime militia has swarmed hundreds of boats around Philippines-administered Thitu (Pag-asa) Island (apparently to complicate Philippine construction activity there), rammed a boat near Reed Bank (where the Philippines enjoys legal sovereign rights to resources), and made multiple unlawful transits through Philippine waters.

The U.S. presence in the region is clearly not preventing all suspect Chinese activity. However, its strong, explicit assurances of its obligations under the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty have helped limit such moves. Most notably, the Chinese have refrained from reclaiming or building on Scarborough Shoal. Without the VFA, which helps operationalize these treaty commitments, the Philippines will be at the mercy of China. That weakness will further fuel the passive approach to China’s aggression promoted by President Duterte, against the advice of his security establishment and the wishes of his pro-American electorate.

Facts & figures

Vietnam

Tension between China and Vietnam flared last year over the deployment of a Chinese survey ship, along with coast guard escorts, near Vanguard Bank in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The ostensible reason for Beijing’s move, in addition to survey activity, was its objection to a Vietnam-sanctioned drilling operation by Russian company Rosneft. Although not as dramatic as a similar standoff in 2014, the crisis was far worse than any of the many incidents since that time – it involved more than 100 ships.

Moreover, there are signs that the episode may be encouraging Vietnam to reconsider its strategic neutrality. First, it led Hanoi to consider filing an arbitration case under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Second, Vietnam’s 2019 Defense White Paper, its first in 10 years, indicates new interest in security cooperation and coordination with other countries, including the U.S.

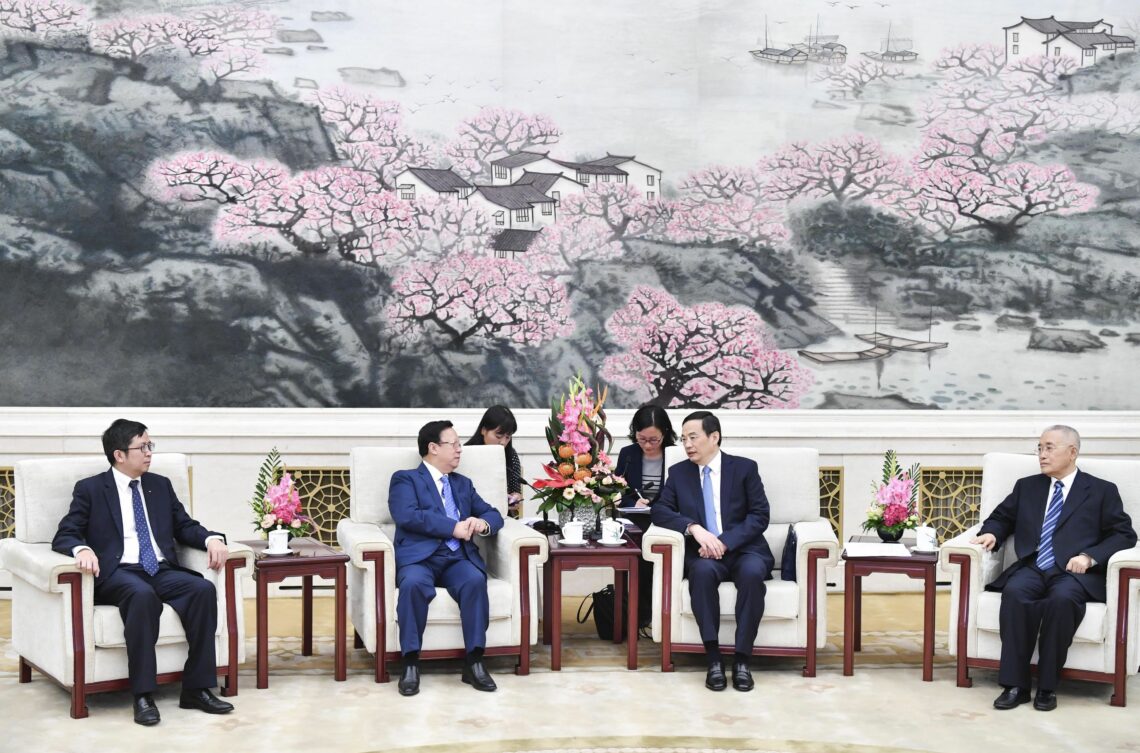

Yet the broader context must be kept in perspective. The Vietnamese and Chinese enjoy regular contact through an extensive framework of bilateral diplomacy and party-to-party ties. Spats between the two are often followed by conciliation. After the Vanguard Bank incident, the two countries held working-level talks on maritime cooperation in Vietnam and a delegation from the Vietnamese foreign ministry visited Beijing to discuss a large range of issues. In January, the heads of their respective communist parties held phone talks to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the China-Vietnam relationship.

Strategic change does not come quickly or easily for Vietnam, which lives in the shadow of a giant neighbor. Meanwhile, the most likely counterweight to China’s power, the U.S., has been hobbled by its perceived unpredictability.

In the near term, the most probable course for Vietnam is allowing its 2020 chairmanship year of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to play out, using it as it did in 2010 to subtly bolster its diplomatic position. Over the longer term, its near-constant run-ins with China at sea, the capitulation of the Philippines to Beijing and China’s ability to control the flow of the Mekong River may cause Hanoi to reevaluate its options.

Vietnam may therefore see filing suit against the Chinese in the Permanent Court of Arbitration and taking small steps in its relationship with Washington as its best course of action. These steps could range from changing the way it formally characterizes its security partnership with the U.S. (currently not a “strategic partner” like China) to high-level exchanges, to arms purchases.

Indonesia

Indonesia’s South China Sea crisis came in December. A flotilla of dozens of Chinese fishing boats accompanied by coast guard escorts entered Indonesia’s EEZ north of the Natuna Islands. The Chinese may have judged the escorts necessary because of the way Indonesia has often dealt with poachers in its waters – by seizing and scuttling their vessels, as provided for under international law. The Indonesian Navy has openly clashed with the Chinese fishing fleet, sometimes firing warning shots. In a tense 2016 confrontation, the Chinese coast guard took back a trawler that the Indonesians had previously confiscated.

Perhaps chastened by the reaction it provoked, the Chinese refrained from intervening in subsequent Indonesian interdictions that spring. The 2016 clashes had led Indonesia to reinforce its military presence in and around the islands and to follow through on plans for a military base there. To make a point about Indonesian sovereign rights, in 2017, it renamed the area under dispute the North Natuna Sea.

The Indonesian Navy has openly clashed with the Chinese fishing fleet, sometimes firing warning shots.

This time, too, Indonesia deployed naval vessels, as well as fighter aircraft. Indonesian President Joko Widodo made a highly publicized visit to the islands, during which he called for “no compromise.” To draw a legal line under the Indonesian response, Minister of Foreign Affairs Retno Marsudi said, “Indonesia will never acknowledge the Nine Dash Lines claimed by China. … All we want is for China as a party to UNCLOS to abide by what’s in there.”

Indonesia’s response tends to be the opposite of Vietnam’s. After major maritime confrontations with the Chinese, the Vietnamese are typically eager to paper over differences and get on with the broader relationship. Indonesia generally stands its ground.

China’s provocations of Indonesia are perplexing, since Jakarta would prefer to not engage in the dispute. For decades, it has considered itself a non-claimant based on assurances Beijing gave it in 1995. The overlapping claims involve no issues of sovereignty over land; China does not claim the Natuna Islands. Rather, its nine-dash map and what it considers its historic fishing rights therein overlap Indonesia’s EEZ, where Jakarta has exclusive rights over fisheries and energy resources.

Indonesia is a traditional stakeholder in ASEAN. In the absence of direct conflicts with China, it would content itself with ineffectual diplomatic intricacies. When provoked, it has the distance that Vietnam lacks, and the pride that the Philippines does not have, to fight back.

Scenarios

The most likely near-term outcome in the South China Sea is that the claimant states and Indonesia will become increasingly assertive. Malaysia has also been rattled by Chinese declarations of extra-legal maritime rights and has begun to subtly push back by appealing to its rights under UNCLOS.

ASEAN meetings in Vietnam this year will produce statements with weak reference to the South China Sea. ASEAN officials will claim these references have significant meaning, but that meaning will be barely perceptible to any neutral observer.

Likewise, there will be regional fanfare over the next stages in developing a “code of conduct” to govern behavior in the Sea. However, progress toward this nearly 30-year-old goal will be tentative.

On the other hand, fears that Chinese negotiators will somehow find a way to push powers like the U.S. out of the region will prove unfounded. ASEAN’s consensus-based process is frustrating for outsiders, but this is no less true for the Chinese than the U.S. The difference is that the Chinese know this and play the game.

Meanwhile, more incidents involving Chinese fishing vessels and coast guards should be expected. One could speculate that, with China facing the coronavirus and unrest in Hong Kong, it would wish to tamp down regional concerns about its aims in the South China Sea. It is not clear, however, that these conflicts were initiated by the leadership in Beijing.

In the longer term, China will continue to strengthen its military and paramilitary posture in the area – with only the U.S. in a position to challenge it, if at an ever greater prospective cost. To cope with the challenge, the U.S. will narrow its interests to freedom of navigation, over time leaving the region to its own devices.