Chinese trade data ring a bell

The latest batch of Chinese trade figures shows an unexpected decline in exports and imports. On the surface, the data can be dismissed as a statistical blip caused by importers reacting to Sino-American trade tensions. Drill down a little deeper, however, and one begins to see bigger problems for China’s economy.

In a nutshell

- Importers’ reactions to trade tensions may explain a late downtick in Chinese exports

- However, the data may also be an early warning of bigger, structural issues

- Misplaced investment has stalled productivity gains, driving up Chinese labor costs

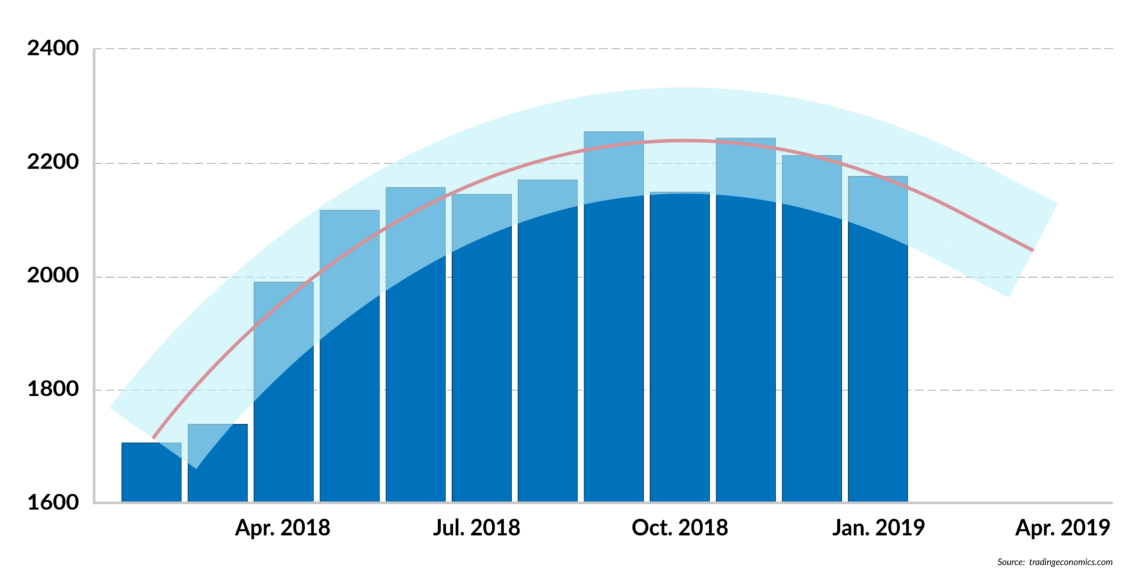

A few weeks ago, the foreign trade statistics for China delivered unexpected news: after having risen for the entire year, in December 2018 exports fell 4.4 percent from a year earlier. Imports also declined significantly (-7.6 percent). Most commentators argued that the slump in these key indicators was a consequence of prior frontloading. Throughout 2018, as importers grew increasingly fearful that commercial tensions between the United States and China could escalate into a trade war, they made sure to place orders before the higher tariffs (or more restrictive quotas) took effect.

The result was record growth (almost 10 percent) for Chinese exports in 2018, and an even faster acceleration of imports (almost 16 percent higher on the year). In this context, December’s figures simply mark the end of the front-loading period; trade flows that normally would have been registered in December had already been logged in previous months. Extending this logic, one should expect the trade data in the early months of 2019 will still suffer from the previous year’s front-loading operations. However, as the situation normalizes in the second half, the long-term upward trend in trade volumes should resume.

Reasonable forecast

Two other considerations weigh on forecasts of Chinese trade flows in 2019. First, many observers expect Chinese economic growth to decelerate. Sluggish domestic demand will inevitably diminish the appetite for imports and, at the same time, boost exports as Chinese companies try to compensate for weaker domestic sales.

Second, there is a growing sense that Sino-American trade tensions have probably peaked and that a prudent thaw is underway. If these guesses are confirmed, a rise in Chinese imports from the U.S. will probably be part of the deal. This would suggest that the softer December trade data are just a statistical artifact, and that double-digit growth in Chinese trade flows will return.

Chinese labor costs are now close to some EU countries and well above many investment destinations in Asia.

This is certainly a reasonable scenario, and it sounds particularly persuasive if one considers that the Chinese authorities need a healthy trade environment to execute a politically hazardous soft landing of their economy. Expansion of China’s gross domestic product has been slowing steadily since 2010 (when the annual pace was still 12 percent), and some fear the headline growth figure could drop below 6 percent in 2019.

Costly labor

We do not deny that the above scenarios are sensible and realistic. Yet, we posit that the December data are not entirely an accident, and that the Chinese economy could be facing structural trade problems regardless of current disputes with the American administration.

Of particular note, Chinese labor costs have risen considerably over the past decade. On an hourly basis, they are now close to levels in some European Union countries, and well above many investment destinations in Asia, including India. Chinese labor productivity is still rising fast (at an annual rate of 6.8 percent, according to official statistics), but productivity growth has fallen off steadily from its nearly 10 percent rate a decade ago. One suspects that the true figures may be even worse than the official data.

The main explanation for these changes in productivity has been their dependence on massive capital investments. Until now, access to more fixed capital (machinery and equipment) has been more important to productivity gains in China than improving the quality of the workforce (through better motivation and skills). Unless something fundamental changes, it should not be assumed that Chinese productivity will continue to exceed or keep pace with the rising cost of labor.

An increasing body of evidence suggests that a large portion of investment in China has been misplaced. These outlays are included in the national accounts, which helps explain the continued spectacular performance of GDP growth. Bad investments, however, fail to raise the productivity of workers operating this inefficient equipment. In a state-controlled economy, the production of useless machinery can be claimed as an output increase, but these unsold or unused products contribute nothing before they are relegated to scrap. Such waste is not captured by Chinese data on productivity and competitiveness in export markets.

Productivity challenge

China’s hidden labor productivity problem is arguably the main economic difficulty it now faces – at least as important as the trade questions that have been making headlines over the past year. In this context, the trade data operate as an early warning system about the clouds gathering over the Chinese economy. Dealing with the quality of workforce and coping with rapidly growing labor costs will be Beijing’s main challenges over the next few years. Depending on the authorities’ response, different policies could be adopted and different scenarios elicited, even in the short run.

Not surprisingly, there is no quick-fix solution to the problems raised by an unskilled and insufficiently motivated labor force. China is about to reach a stage where it will have difficulty competing with low-cost producers like India or Vietnam, which have an abundance of labor willing to work for less than 50 percent of the Chinese rate.

If nothing changes, Chinese producers will find themselves displaced by low-cost competitors in several key export markets, and might even find themselves challenged on their home turf. Western companies may also reconsider their investment strategies and divert resources and production capacity to other Asian countries. This will cause the Chinese to miss out on opportunities to upgrade their know-how, which will now flow to their cheaper rivals.

What this shows is that the trade dispute – however important – should not be used as a simple explanation or excuse for disappointing economic performance in China. Weaker-than-expected exports are not simply a function of political tensions and statistical accidents. At a deeper level, they are a consequence of structural difficulties.

Risky options

China will of course spend massively to upgrade its workforce. There will be more and better training, stricter quality controls and tighter monitoring against slackers. However, all these measures will take time. To achieve short-run results, two options are available – both of which might lead to unpredictable tensions.

One involves freezing the cost of labor. A system of wage and price controls would help boost corporate profitability and delay offshoring by foreign and Chinese firms. It would allow the Chinese authorities to buy time before the benefits of a more productive workforce become evident. The drawback, however, is that any tampering with the spontaneous operation of labor markets quickly produces distortions. Such controls are often easy to circumvent, and even when obeyed, tend to discourage productive entrepreneurship.

The high-tech solution involves leaving unskilled workers behind; social and political tensions would ensue.

The second option involves a technological upgrade of manufacturing – replacing masses of low-skilled workers with more sophisticated machinery, including robots, operated by a many fewer skilled workers. In this case, however, the result is labor-market polarization (setting a small fraction of well-paid specialists against a billion low-skill, low-wage workers). It also sends China into uncharted waters, competing for higher market segments now dominated by the advanced economies.

Social eruption

Beijing will almost certainly meet failure if it tries to freeze labor costs. The required monitoring system would be both cumbersome and ineffective; by giving more power to central planners, it would also feed corruption and uncertainty.

The more probable scenario is the high-tech solution, but this would involve leaving unskilled workers behind. They would suffer badly, and the unemployment rate will rise. One wonders whether China can bear the social and political tensions that would ensue.

It follows that China-watchers and students of the global economy should turn their attention away for the soft-landing process and the hairsplitting debates over what rate of GDP growth will be tolerable for 2019. Rather, the foreign trade data will tell us whether Chinese productivity and labor costs are compatible, or whether they are leading the Asian giant toward scenarios of high, and possibly hidden, unemployment. If the latter occurs, the map of world trade might change dramatically and social tensions could erupt within China, no matter what happens to economic growth.