2019 Global Outlook: The economy we left behind

2018 was not a bad year for the world economy, and 2019 should be only a little worse. There was satisfactory growth and a long-overdue cleanup on financial markets. 2019 will be more sluggish as China keeps slowing and the U.S. spurs commercial tensions.

In a nutshell

- Both global trade and economic growth have been holding up remarkably well

- The economy will stay resilient in 2019, but sluggish investment and trade tensions will take a toll

- Decisions by Western policymakers will also be key; right now, they seem pessimistic

All in all, 2018 was not a bad year. If one looks at the broad picture, three major threats did not materialize. International trade was harmed, but not seriously disrupted by President Donald Trump’s protectionist policies in the United States; global growth was satisfactory; and no large country suffered a public-finance crisis. On the other hand, last year also failed to provide credible solutions to several outstanding issues, a consideration that weighed on financial markets and will certainly carry over into 2019. Let us analyze the various points in order.

It is still too early for full-year data on world trade in 2018. Most commentators agree, however, that the expansion in trade volume was between 3.5 percent and 4 percent (in January 2018, we predicted world trade would grow at a better than 3.5 percent rate). This is quite satisfactory, especially in comparison with the 2.2 percent average annual growth rate of world trade between 2000 and 2014. For the record, at the beginning of 2018, the World Trade Organization was forecasting trade growth of 4.4 percent, although it added that any figure between 3.1 percent and 5.5 percent would have been possible.

More importantly, one should note that if global trade did expand by less than 4 percent, this would not have been due to sluggish global economic growth, but to the tensions unleashed by the current U.S. administration. This suggests there is scope for significant and quick improvement should the major trading powers patch up their differences.

Remarkably robust

As mentioned earlier, worldwide economic growth has not been disappointing. The average rate of expansion was about 3 percent between 2010 and 2016, inching up to more than 3.1 percent in 2017 and 2018. Especially noteworthy is that the much-dreaded Chinese crash did not occur. As we predicted, growth in China’s gross domestic product (GDP) did slow down, but only fractionally: from 6.7 percent and 6.8 percent (in 2016 and 2017, respectively) to about 6.5 percent in 2018.

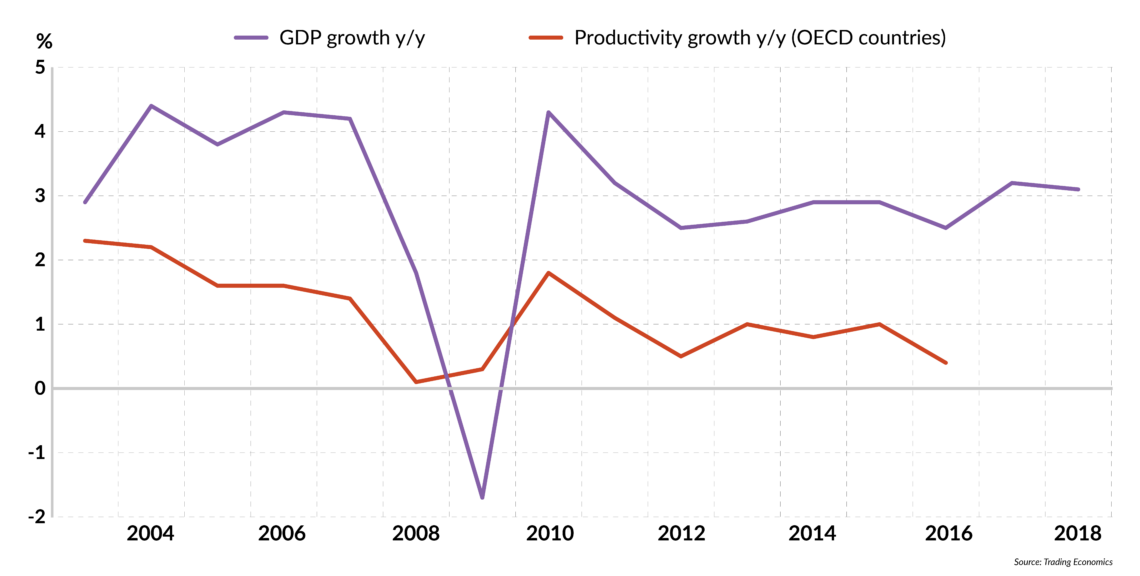

As a matter of fact, the global data are remarkably strong, since productivity is stagnant in the advanced economies and declining globally. This means that the engine of economic growth has been massive investment in production facilities and equipment. In other words, the great financial crisis of 2008-2009 did not usher in a period of secular stagnation.

Facts & figures

World growth and productivity

One wonders, however, just how long these satisfactory growth figures will continue. Investments do enhance growth, but they peter out if not sustained by solid productivity gains, which derive from a better labor force, more competitive pressure and renewed entrepreneurial enthusiasm.

Last, but not least, the major financial crash so often predicted for 2018 did not occur. Consistent with our predictions and despite widespread pessimism, financial markets weakened but did not collapse: the Dow Jones Global index closed about 12.2 percent lower on the year (17 percent weaker if one excludes U.S. equities), and the bond market fared little better. Certainly, these declines produced substantial losses for many investors. Yet, they look like the outcome of a healthy correction rather than a catastrophic breakdown.

Take your pick

Thus, the outlook for 2019 is encouraging – with prudence. This judgment is based on what looks like sustainable global growth, satisfactory corporate profitability, and improving public finances in three key areas. In the euro area, budget deficits have been – and will be – contained; China’s public expenditure is still on the rise but not out of control; and some heavily-indebted undeveloped countries have benefited from a lower-than-predicted rise in dollar-denominated yields and stable servicing costs on euro-denominated debt.

In this light, the scenarios for 2019 will ultimately depend on whether one believes that last year’s critical issues have been kicked down the road or successfully addressed. If the latter, one can safely forget about them.

2019 will follow the long-term trend of declining productivity gains and a weaker contribution from China.

Our answer is mixed. Last year offered no adequate reply to key long-term questions and bottlenecks, but it also suggested that no catastrophic events are imminent. That does not mean major shake-ups are ruled out, only that if they occur, they will be the result of accidents rather than simmering tensions inherited from the past.

Slow ahead

In terms of global performance, 2019 will follow the long-term trend of declining economic growth driven by disappointing productivity gains (a key unresolved issue) and by a weaker contribution from the Chinese economy, which will keep slowing. In hard figures, this means that unless China improves upon its 2018 growth performance (and it will not), and unless investments in Europe and the U.S. pick up substantially, global growth will not be much higher than 3 percent. This prediction is based on several elements that will become evident in the forthcoming quarters.

First, the trade tensions of 2018 will carry over into this year. We do not believe that the world is doomed to a global trade war. In fact, some thawing is already visible. However, the year we have left behind has made clear that world leaders are unable or unwilling to make credible long-term commitments. Opportunities have been lost.

The business community is persuaded that trade tensions will persist until late 2020, when the next U.S. presidential elections will be held, and possibly longer, if the incumbent president is reelected. In consequence, entrepreneurs remain cautious, and investments will suffer. A low rate of investment is a further drag on productivity growth. Some evidence to this effect was already evident toward the end of 2018.

Chinese switch

Secondly, much of China’s economic growth is dependent on the construction sector, whose expansion seems to have a life of its own even when it produces empty residential and office facilities. This is not sustainable and will become an insupportable burden for those banks involved in financing the industry.

The authorities will probably engineer a switch from the construction and the export sectors to domestic consumption, which will help moderate the slowdown. But as oversupply is burned off, and pressures to cut the foreign trade surplus intensify, slower economic growth is inevitable.

We believe that China’s GDP can still expand at the rate of 6 percent. This would be a tolerable pace, despite alarmist cries in Western quarters. Yet, if the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is on the mark in its prediction of a “mere” 5.6 percent performance, then the global psychological impact will be substantial.

Mixed messages

Thirdly, the prospects for the U.S. economy are good, but far from stellar. The recent high growth rates were not due to better overall conditions, but to a generous tax reform that boosted corporate investments. Its effects might fade away in 2019, which cannot be said about the federal budget deficit. Nobody knows how the Trump administration will react to the challenge posed by rising indebtedness. It will certainly increase uncertainty, and greater uncertainty never encourages growth.

Finally, the quality of economic policymaking in the Western world will also play a significant role in defining which scenario emerges this year. The outlines of monetary policy at the major central banks are beginning to become clear. As we pointed out in December, both the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, in contrast with their earlier announcements, will follow a rather accommodating strategy. This means that real interest rates will stay low (and lower than anticipated). This is surely good news for heavily indebted companies across the world. Yet it is not a good message sent out to those with healthier balance sheets and cash to spend on new projects.

The persistence of abnormally lax monetary policies testifies to policymakers’ fear that taking a different approach would thwart growth. It sends a pessimistic signal to those in the know. The probable effect will be to deter those who can and perhaps even should invest. Instead of taking steps to improve their competitiveness and productivity, many such investors will hold their fire and wait for the clouds to lift.

This reaction is reasonable and prudent, but hardly conducive to global economic growth. The other side of that coin, however, is that troubled companies will have one more year to put their financial house in order.