Colombia’s outlook darkens

After a generations-long internal conflict and controversial peace agreement with a narco-terrorist group, Colombia can no longer fall back on its economy. Enter the pandemic, and the daunting economic and social challenges faced by President Ivan Duque become clear.

In a nutshell

- Colombia's goal of a quick post-conflict recovery has proven elusive

- The country remains the world’s largest cocaine producer

- Venezuela’s failed-state status and the pandemic further cloud Bogota’s options

Colombia is South America’s oldest democracy and a founding member of the continent’s largest free-market trade bloc, the Pacific Alliance. The Andean nation is also home to the Western hemisphere’s longest-running civil conflict, which has continued for more than 56 years, claiming upward of a quarter of a million lives and internally displacing seven million Colombians. Fueling the violence and funding the civil war has been the lucrative narcotics industry and as the world’s largest cocaine producer, a recovery in Colombia forebears a great economic challenge.

Challenging peace agreement

Four years ago, the Colombian government finalized peace talks with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a transnational narco-terrorist group. After five years of intermittently stalled peace talks hosted in Havana, both sides came to a wide-ranging yet polarizing peace agreement. When initially put to a vote in a referendum, Colombians narrowly rejected the deal in 2016. Congress later passed it after government and FARC negotiators adjusted parts of the accord.

Colombia is at an inflection point and faces many severe challenges as it moves forward with trying to implement the peace agreement and forge ahead with ending the internal conflict. President Ivan Duque of the center-right Democratic Center party was elected a thin margin in 2018 in a vote focused mainly on Colombians’ concerns over the previous government’s flawed approach to the peace process and economic fragility. Mr. Duque is seen as a protege of former President Alvaro Uribe, whose heavy-handed approach defeated the FARC militarily. However, Mr. Uribe is a politically divisive figure.

The border with Venezuela makes the neighboring humanitarian crisis a costly domestic economic challenge for Colombia.

The peace agreement remains a polarizing issue both within Colombian society and among political actors. Critics contend that despite its laudable intentions, the negotiating government prioritized the deal at the expense of uniting the country behind a palatable arrangement, as evidenced by the failed referendum vote. Today, peace opponents continue to point to the same flaw of the deal: citizens and victims’ inability to hold FARC accountable at levels proportional to Colombia’s traditional justice system.

Venezuela’s implosion

Colombia’s nearly 1,400-mile (2,250-kilometer) border with Venezuela makes the neighboring humanitarian crisis a costly domestic economic challenge and a critical foreign policy dilemma for Colombia. Since 2013, an estimated 2 million Venezuelan refugees (out of the country’s exodus of 5 million) permanently resettled inside Colombia. Tens of thousands of Venezuelans traveled through Colombia en route to regional countries before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Venezuelans born in Colombia from August 2015 to 2021 are legal Colombian citizens with access to additional social services. Even if Venezuela’s political crisis is resolved soon, the economic devastation will take time to mend, meaning migrants will continue arriving in Colombia. Before the pandemic, multilateral organizations were reticent to support Venezuelan refugees. With the global need for humanitarian assistance increasing, there is little indication that will change shortly.

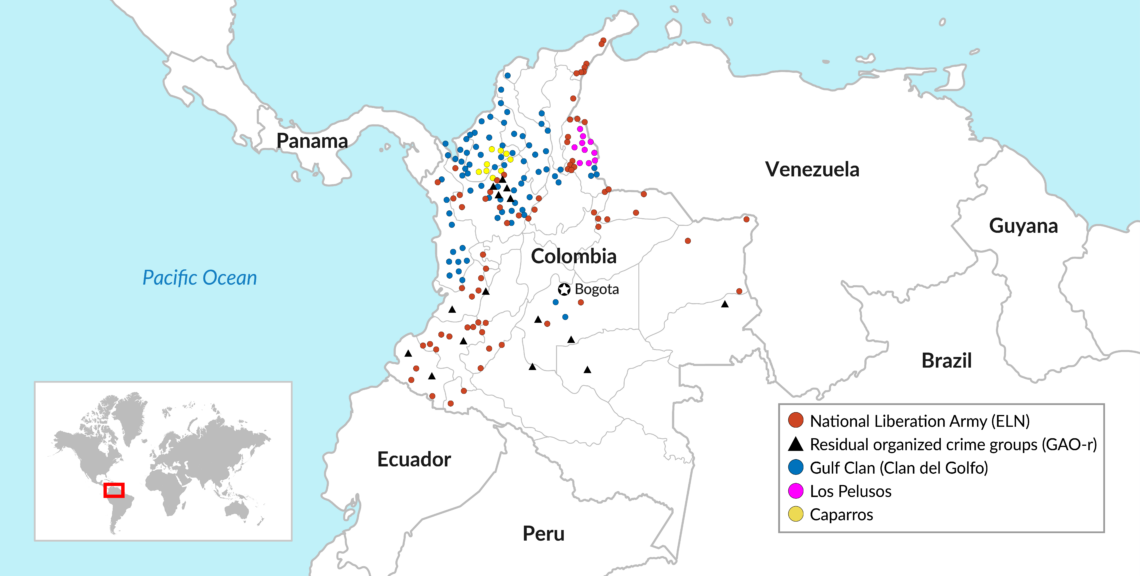

Facts & figures

Attempts to implement the peace agreement are regularly undermined by the Maduro regime’s open support for FARC dissidents absconding from the country and criminal organizations capitalizing on Venezuela’s lawlessness. Former FARC guerillas and members of the still-active National Liberation Army (ELN) terrorist group illicitly control coltan, diamond and gold mines in Venezuela – often in collusion with corrupt regime officials. This allows rogue actors to continue funding subversion against the Colombian state and enriching their criminal organizations. Aside from mining, proximity to the border gives these organizations easy access to trafficking and smuggling networks.

Growing cocaine output

Rampant levels of cocaine production and the persistent challenges to the rule of law are stark reminders that peace and security remain elusive despite the agreement. Despite multibillion dollar Colombian and U.S. investments in eradicating Colombian coca crops and cocaine production facilities, drug production levels are at high levels.

In 2017, the area under coca crop cultivation in Colombia reached a record of 209,000 hectares. Policies adopted during the peace talks have led to the production’s resurgence. The Colombian government decided to end aerial eradication of coca crops during the peace talks, but FARC returned to its old practice of coercing farmers into planting coca toward the end of negotiations.

Aerial eradication of illicit crops was a key component of Colombia’s counternarcotics strategy until a study from the World Health Organization (WHO) on glyphosate, the primary chemical used to destroy coca plants, indicated that it could cause cancer.

A worsening security crisis in rural Colombia has complicated the prospect for peace, notably the increase in violence against demobilized FARC members.

The aerial program was shut down in 2015. The following year, the WHO found out the chemical agent was not carcinogenic after all, removing the initial rationale for the program’s cancelation. However, Colombian security personnel remain tasked with destroying coca crops on the ground, subjecting themselves to severe risks from land mines, gunfire and other forms of violence from criminal organizations. Also, confrontations between soldiers and cocoa farmers are on the rise.

Colombian courts and legal experts are debating whether to restart the aerial program. The resumption timeline is still pending, as the pandemic and mandatory quarantine measures have stalled various nonessential government services. Cocaine production also has increased due to a perverse policy mechanism: farmers who plant more coca help their region by attracting more generous assistance from the outside. The Columbian government and international development agencies tend to focus aid resources on areas with the highest coca growth levels. Colombia and the U.S. have reached an agreement to cut coca cultivation levels in half by 2023. The goal still seems attainable.

Rural violence

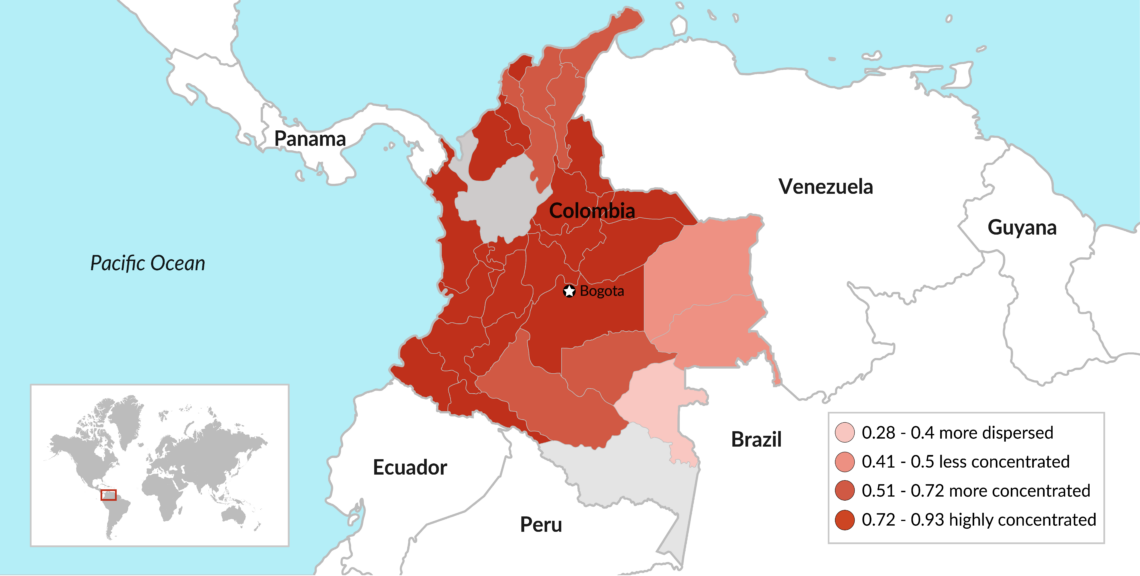

In the backdrop of the rise in cocaine production, a worsening security crisis in rural Colombia has complicated the prospect for peace, notably with the increase in murders and violence against demobilized FARC members and civil society leaders. The Colombian government faces the challenge of not only protecting these key peace process actors but also filling the security vacuum and bringing the rule of law to Colombia’s disenfranchised regions.

Perhaps the most complex challenge for Colombia and the international community to address are the seven million internally displaced people (IDP). While the conflict took an estimated quarter-million lives, managing the drama of the nearly 15 percent of Colombia’s population that is displaced is a multifaceted and potentially multigenerational task. Women and children are the majority affected by the conflict and the largest group of Colombian IDPs, particularly those of indigenous and Afro-Colombian descent.

Facts & figures

A critical element of supporting IDPs entails Colombia formalizing its land titling process. Land issues remain a key component of the peace agreement as it was a root cause of Colombia’s political conflict today. An estimated 15 percent of the country’s land is either improperly registered or unlawfully owned, which means that it was very probably expropriated during the conflict.

Scenarios

The rule of law remains Colombia’s central weakness. Balancing the need for national reconciliation while upholding peace agreement obligations and the need for the rule of law will remain a daunting task for current President Duque and future administrations, regardless of their political affiliation.

Going into the peace agreement implementation, the Colombian government took insufficient measures to protect state institutions’ integrity and prevent FARC agents’ infiltration. FARC members were not obligated to hand over wealth acquired from illegal activity before subjecting themselves to the peace process. As a result, Colombian officials are routinely uncovering undeclared FARC property and bank accounts. This oversight will remain a critical challenge for Colombian policymakers, as FARC is now a political party. The country has a long history with illicit money undermining its electoral process.

With the U.S. presidential election months away, its impact on Colombia and the bilateral relationship will influence the peace process’s trajectory. Regardless of who wins, there is no likelihood that any U.S. administration will soon change its policy on terminating extradition requests for wanted FARC criminals, even though the peace process protects them.

A Biden administration might publicize development assistance over the security aspect of foreign aid. However, ultimately, excluding fringe isolationist elements in both parties, there is broad bipartisan consensus on the Colombia policy. Consistency should be expected.

President Duque’s and his administration’s image among Colombians has been colored by their close relationship with former President Uribe. As Mr. Uribe is now under pretrial detention (his alleged offenses include fraud, bribery and witness tampering), the rest of the Duque administration's credibility will be measured by how the Uribe case proceeds. There is a scenario in which Mr. Duque’s political future is protected as long as Colombia’s economy can bounce back quicker than those of its regional neighbors. Heading into the health crisis, Colombia was Latin America’s fastest-growing economy, which helped offset political instability in the past.