Colombia: Organized crime at the heart of unrest

The recent positive economic figures from Colombia belie the country’s continuing struggle with organized crime and violence. With the growth of the middle class, Colombians are becoming less ideological and are calling for more centrist policies to address these issues.

In a nutshell

- Colombia’s economy is recording healthy growth

- Large regions remain under the control of armed groups

- Protesters want greater security and help for rural areas

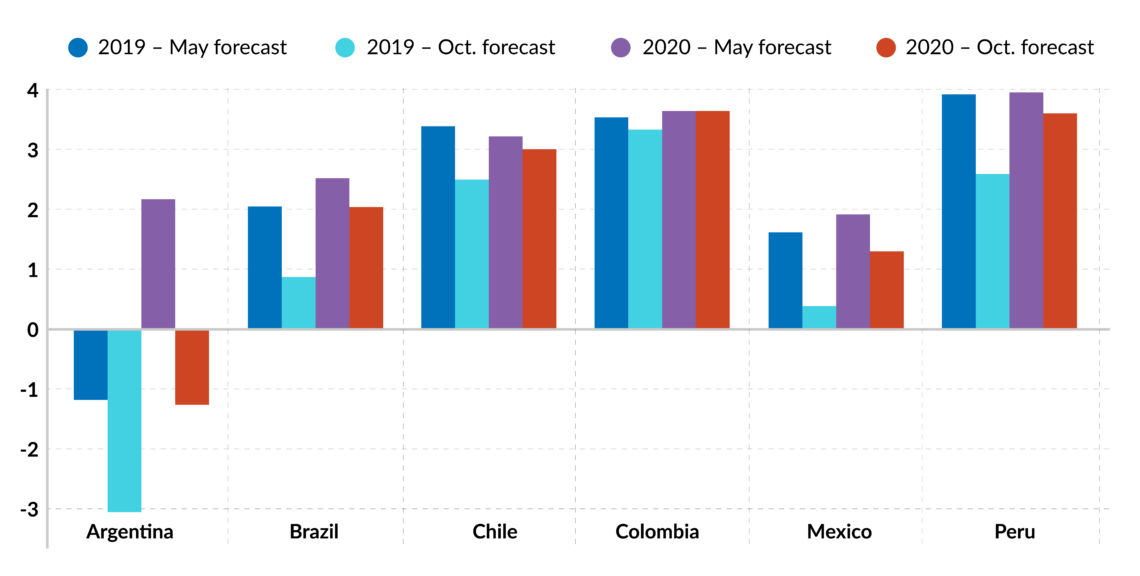

In Colombia, as in other South American countries, demonstrators have taken to the streets to protest the government. Yet while the country’s social unrest shares many characteristics with Chile’s, it is fundamentally different from the protests in Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. Colombia’s economy is growing faster than almost all the others in South America and, in contrast to most of its regional peers, public opinion is not moving further to the extreme right or left, but toward the center.

In the local and regional elections this past October, the traditional parties of the left and the right lost support. Most of the officials who were elected focused on local issues; they followed the electorate toward the political center and against rigid ideological positions. In 25 of the 32 of the regional elections and in 15 of the local elections, the victors were ad hoc coalitions led by alternative candidates.

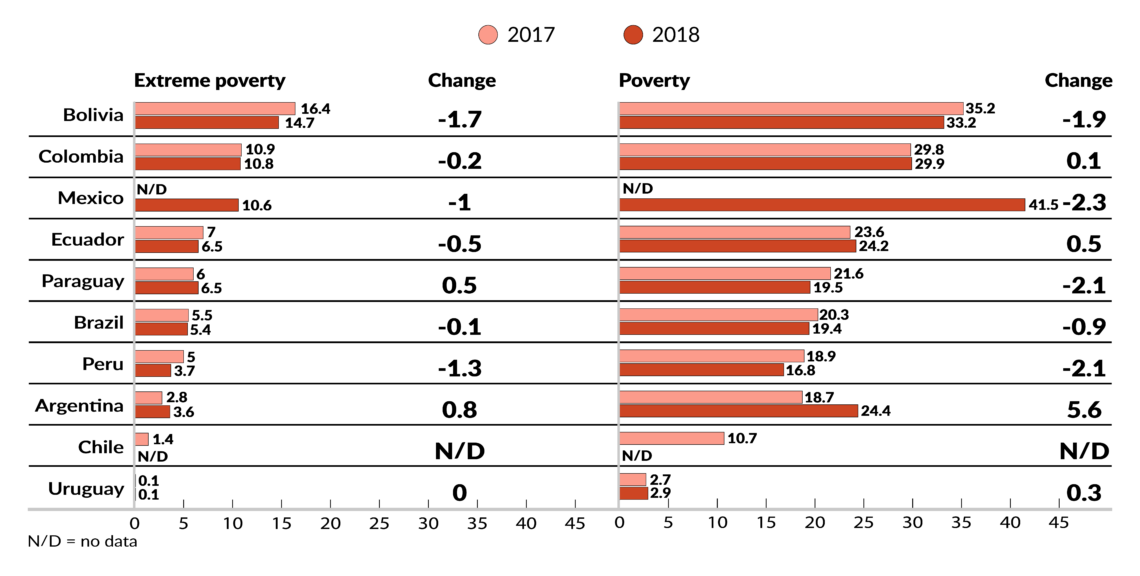

The Colombian economy is relatively healthy: its gross domestic product (GDP) grew by more than 3 percent last year, and the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean expects that pace to continue this year. Most other countries in the region are struggling to reach GDP growth of more than 1 percent. Foreign direct investment in Colombia is growing and poverty continues to decline, as it has for the past decade, though now the reduction is slower.

Economic upturn

In a recent study by the National Association of Financial Institutions (ANIF), the economy includes less informal and illegal activity. While both reflect state capacity, the former is an important indicator of economic health. The study found that informal activity had fallen from 44 percent in 1985 to 30 percent in 2012 and has continued to drop in the years since. Data on illegal activity are less reliable. (The United States Drug Enforcement Agency probably has a better idea of the value of the cocaine trade than the ANIF or the Colombian government.)

The only sour notes are that unemployment ticked up to more than 10 percent and domestic investment was flat. Another factor that could threaten economic growth is the failure of the government to help former conflict zones in rural areas, where the cultivation of illegal crops is expanding. Colombia’s organized crime groups, known as BACRIM, are getting stronger in these areas.

Facts & figures

Political polls indicate that Colombians want to consolidate the gains of the 2016 peace treaty that ended 50 years of conflict with the largest guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Many of them have moved into an expanding middle class and want to reap the benefits of their enhanced status. They are less interested in ideological battles than their forebears 20 years ago. Instead, they are concerned mainly with their personal security, their access to jobs and ending the corruption that for years has characterized both the government and the private sectors.

Rising crime

The first street demonstrations were led by urban groups nervous about economic reforms such as new taxes, proposed changes to the pension system and new labor laws. As the demonstrations continued, the agenda expanded to include demands for greater security and increased investment in rural areas, and faster implementation of the peace accords. There was also concern for the ongoing pattern of assassination of human rights leaders and leaders of the Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities, which have been caught up in the violence.

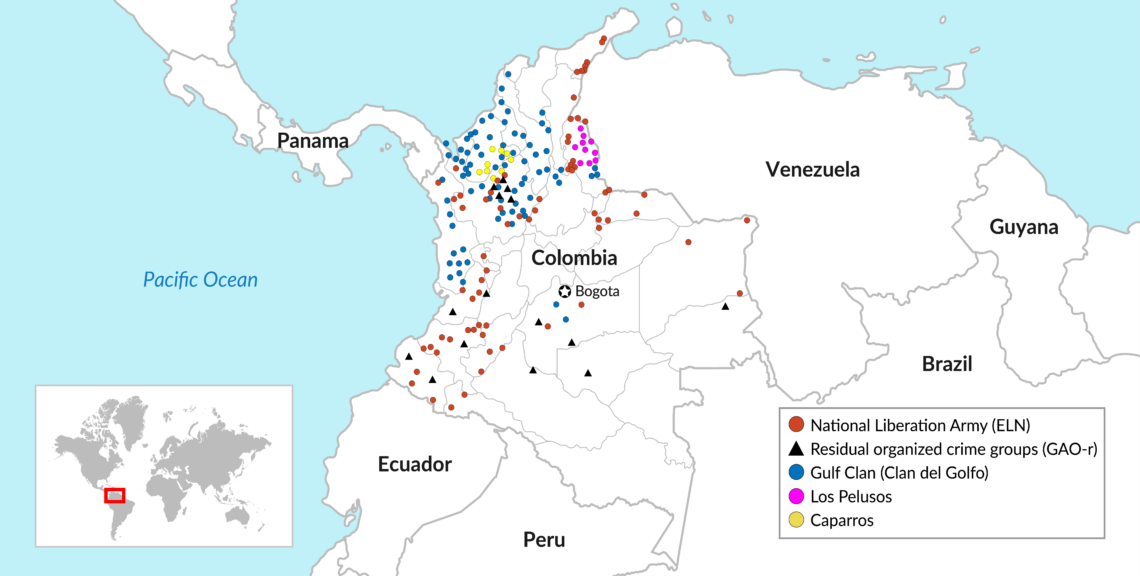

What the economic data do not reveal is that organized crime continues on a scale not seen anywhere else in South America, while the area of the country under the control of the BACRIM continues to expand. This is especially worrisome as the 2016 peace treaty between the government and the FARC led to a marked decline in violence and a significant jump in popular optimism. The resurgence of the BACRIM and the accompanying drug trafficking, violence and illegal mining almost certainly lie behind the malaise expressed by the street violence over the past few months. It is marked in the public opinion polls of those who express their disapproval of the government and President Ivan Duque.

The lack of governance over these zones has a heavy impact on levels of violence.

The geographical distribution of illegal activity is significant. The overwhelming portion of the areas in which the BACRIM essentially replace the state is rural and heavily concentrated along the western and northern parts of the country. The lack of governance over these zones has a heavy impact on levels of violence, the number of displaced people, the security of infrastructure projects, and the continuity of daily life.

The national homicide rate is down, as is the number of displaced people. But the violence and the instability are concentrated in these areas. Cities also have much higher rates of school attendance, which translates into much higher rates of social mobility.

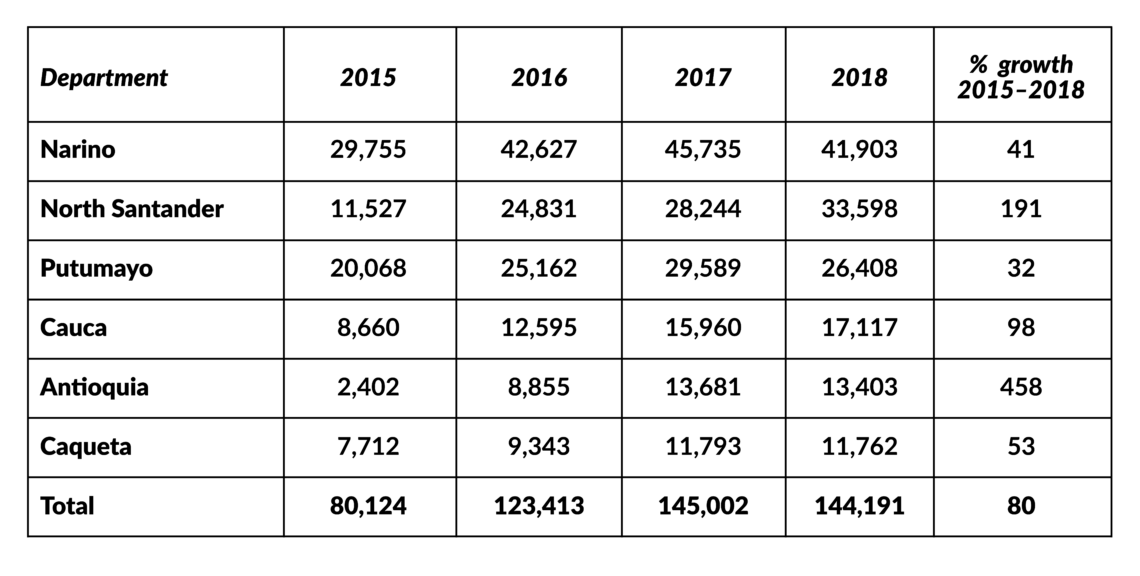

One of the obvious consequences of this pattern of rural violence and the absence of state control is the dramatic rise in the cultivation of illegal crops. Part of the increase results from the termination of U.S.-funded spraying and crop-substitution programs. Relations between Washington and Bogota have become strained due to the end of these programs and of the increase in coca production.

Facts & figures

Illegal gold mining has increased by 8 percent over the past year, mainly in the departments of Antioquia, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Choco, Cordoba, Bolivar and North Santander. The combination of this activity with other illicit businesses such as narcotics and smuggling has created “conglomerates of illegality” that sustain the BACRIM while hampering economic development.

Inequality and poverty

As Colombia’s middle class expands and becomes more politically active, it is growing increasingly concerned by the country’s economic inequity. Colombia is one of the most unequal countries in Latin America. The Gini coefficient, a common measure of income inequality, has risen over the past two years to reach 51.7 percent. Wealth is more concentrated among the top 10 percent in Colombia than in most other countries in the region. It is no accident that the other Latin American country with a similar concentration of wealth is Mexico, where the drug economy also plays a significant role.

The middle class has another disadvantage in that 52 percent of those 25 years of age and older have less than a secondary education. Some 62 percent of people in the lower-middle class have not finished high school. The lack of education is a serious threat to social mobility.

A more positive note is the continuing decline in the number of displaced people. During the years of civil violence, nearly a quarter of a million people were displaced each year. By the time the peace treaty was signed in 2016, the total number of people displaced by the guerrillas and by paramilitary bands had surpassed four million. Since 2016, the number of declared refugees has fallen to 100,000 per year and the numbers for 2019 indicate that the total will be significantly less. As the terms of the peace treaty are carried out, this number should continue to drop.

Colombia’s protesters are demanding programs that reduce poverty and secure the welfare of the population.

Over the past few months guerrillas and several BACRIM have been fighting for control of strategic regions, generating new internal displacements. The Duque government has sent representatives to these areas but for now there is no clear strategy to bring areas with high levels of illegal economic activity (such as growing illicit crops, illegal mining and cocaine production) under state control. These regions include Antioquia, North Santander, Narino, Arauca, Choco, and Cauca.

Colombia’s protesters are demanding programs that reduce poverty and secure the welfare of the population. In a nod to these demands, President Duque announced measures to eliminate the value-added tax (VAT) for three days each year, to reimburse VAT payments to the bottom 20 percent of households by income, and to reduce the 12 percent mandatory contribution that pensioners make for health insurance to 4 percent.

Facts & figures

Colombia remains one of the more attractive countries in the region for foreign investment. In the first half of 2019, foreign direct investment (FDI) totaled more than $7 billion, an increase of 24 percent over the same period of the previous year. Mining and petroleum continue to be the main sectors for foreign investment, although financial services and manufacturing have shown considerable strength.

Perhaps the greatest potential for foreign investment lies in the shale deposits in the Middle Magdalena Valley. With Colombia’s conventional petroleum reserves nearly exhausted, the shale reserves are particularly valuable. Ecopetrol, the largest oil company in Colombia, is in charge of the fields. Shell and several other international firms have indicated their interest.

Still, with oil prices between $55 and $65 per barrel, it is not an investment firms are rushing to make. While the success of the U.S. shale industry is something investors may want to repeat, the recent low oil prices have made them somewhat more cautious. Moreover, investors are already waiting to see what the new government in Argentina will do to open up exploitation of the vast shale reserves in the Vaca Muerta region of Patagonia.

More than one million Venezuelans are now living in Colombia, almost half of them stuck in tent settlements near the border.

One of the most serious problems facing the Duque government is the huge number of refugees from Venezuela. More than one million Venezuelans are now living in Colombia, almost half of them stuck in tent settlements near the border between the two countries. Most of the cost of dealing with these refugees is met, at least for the moment, by the United Nations and other international donors. The Colombian population was largely welcoming to this influx; but, over time, their opinions have become more negative. As unemployment ticks up, hospitality for the Venezuelans will become more complicated.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario over the next six months is that President Duque will show his pragmatic side in dealing with the social unrest. He already has the laws in place to provide at least some relief to the most vulnerable in society and will attempt to appease the protesters with modest proposals. In this effort he will be aided by the continuing strength of the Colombian economy. He recently won legislative approval of a major tax reform bill. It also looks likely that a constitutional amendment, designed to stabilize the rules for foreign investment, will be approved in the near future.

President Duque will certainly try to deal with the problem of rural violence and the absence of state control in areas where the BACRIM are active. He also will reach out to the UN, the U.S. and to his neighbors in Ecuador and Peru in an effort to construct a regional solution to the problem of Venezuelan refugees. Moreover, he will move to strengthen his support from the coalition of parties that helped get him elected. As the Colombian public moves to the center, these parties will understand the importance of keeping President Duque in power.

A less likely scenario would see President Duque rendered impotent by a combination of hostility from the right-wing parties that helped elect him and the state’s inability to rein in the widespread violence and criminal activity in significant portions of Colombia. Under this scenario, the Trump administration will refuse to help President Duque and, instead, will penalize him for the increase in coca cultivation and drug trafficking. The U.S. Congress has already made aid to the Colombian government conditional on the Duque government fulfilling the terms of the peace accord with the FARC.