Colombia’s president juggles Venezuela, Trump and a shaky coalition

President Ivan Duque has a thankless job to meet the challenges of Colombia. The attempt to end the 50 year-long civil war has proven hard to implement, as millions of people were displaced and disenfranchised in that war. And a rise in coca cultivation displeases the U.S. Signals from the country’s economy, however, remain optimistic.

In a nutshell

- Colombia’s economy forges ahead and foreign investment is flowing in despite major security and social challenges, and the government’s political frailty

- Most Colombian voters believe the former guerrillas were treated too generously in the recent peace accord

- President Ivan Duque is trying to preserve peace, address the most burning social issues, neutralize domestic rivals and please Washington at the same time

At this juncture, nearly a year into his term as Colombia’s president, it is hard to imagine that Ivan Duque is not asking himself why he wanted the job. It is not so much that the country’s problems are intractable – although they are – as that he must navigate internal political struggles that make it almost impossible for him to tackle them. Mr. Duque does have two things going for him: the political opposition is hopelessly fragmented and the economy keeps growing with no signs of impending collapse. Meanwhile, he must govern.

President Duque’s first challenge is to manage the ambitions of his patron, former President Alvaro Uribe Velez (2002-2010), who is working assiduously to strengthen his own party, the Democratic Center, in the regional and municipal elections scheduled for October. The greater Mr. Uribe’s success, the more it will undermine Mr. Duque’s efforts to keep together the coalition he built for his presidential campaign. Without this broad base of support, the president cannot pass any legislation through the Congress of Colombia, where Mr. Uribe’s party controls only one-fifth of the seats. At the same time, public opinion surveys make it clear that Mr. Uribe’s popularity is fading; to the extent that President Duque appears to do his patron’s bidding, his own popularity suffers.

Deal adjustments

An even bigger political threat to Mr. Duque is his increasing inability to fulfill his signature campaign promise of revising the peace accords with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Most Colombian voters believe the former guerrillas were treated too generously in the original agreement. The process Mr. Duque has chosen to accomplish this goal is to push through the Congress a series of “objections” to the key element of the peace process, the Special Transitional Justice Tribunal (known by its Spanish acronym, JEP).

The JEP will also be a litmus test of the president’s independence from Mr. Uribe.

The JEP’s legitimacy has already been upheld by Colombia’s Constitutional Court. Its duties include adjudicating accusations against former combatants on both sides of the 50-year conflict and supervising restitution claims from victims of crimes committed during the conflict. With the institution slowly gaining public support, President Duque will need more than the legislature’s support to roll back the JEP’s prerogatives. Ultimately, it will be in the hands of the Constitutional Court to revisit its decision and determine the future contours of the tribunal.

Here again, Mr. Uribe is more of an obstacle than a support. His Democratic Center party insists that no member of the armed forces that fought against the FARC should be tried for any crimes they may have committed. President Duque’s popularity with the voters, however, hinges on whether the peace process is carried out and is perceived as bringing justice to both victims and perpetrators. The JEP will also be a litmus test of the president’s independence from Mr. Uribe, a highly controversial figure.

Given these complications, it is no surprise that the Duque government is finding it difficult to carry out the terms of the peace accords. Tens of thousands of claimants are seeking compensation or restitution for what they say was taken by the FARC, paramilitaries, and organized criminal gangs (known in Spanish as BACRIM). For their part, former FARC combatants are trying to secure land or other social benefits they were promised under the accord. To make matters worse, information has been leaked to the press in Colombia and elsewhere that the army has ordered troops to shoot to kill in their engagements with guerrillas. That can only lead to increases in civilian casualties.

Social problems

In this context, it is important to remember that Colombia’s 50-year civil war was waged to force the government to conduct an agrarian reform. At least for now, the authorities have been unable or unwilling to provide state agencies with the resources to carry out this agricultural reform mandate of the peace process. The immediate consequence of this failure to move ahead at a reasonable pace is that many of the former combatants have taken up arms again, either with the holdout guerrilla force, the National Liberation Army (ELN), or with ad hoc armed groups known as the FARC Dissidents.

The United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia, along with the United States and various European states, have warned the Duque government that it must do a better job of carrying out the peace accords. Here, as with the other problems Mr. Duque is facing, the country’s weak institutions are a severe handicap.

The most serious social problem that President Duque inherited from his predecessors is coping with the nearly 8 million rural people uprooted by the long guerrilla war. A half-century of turmoil left pockets of vulnerability and large concentrations of displaced people without access to resources. These people, dependent for support on the national and regional governments, are primarily found in three areas: Antioquia, North Santander and Narino. Relieving their misery requires focused policies and the resources to carry them out.

There are as many as 1.9 million Venezuelans in Colombia.

The armed groups along with the BACRIM are also benefiting from President Duque’s newest headache – the massive exodus of refugees fleeing the growing repression and humanitarian disaster of Venezuela under the regime of President Nicolas Maduro. There are probably as many as 1.9 million Venezuelans in Colombia, with tens of thousands huddled in tents along the border.

These temporary encampments have attracted most of the attention, including visits from dozens of senior officials and even heads of state from governments hostile to the Maduro regime. This media attention, at least, has spurred a significant flow of international aid. A less evident, but more difficult problem for the Duque government is what to do about the hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan refugees scattered throughout the rest of the country, who are also badly in need of assistance, trying to establish new lives for themselves and, in some cases, plotting how to get rid of Maduro.

Geopolitical trap

President Duque began by using the migration crisis to gain international stature as the leader of the anti-Maduro coalition. This gambit has not proved as effective as he had hoped and may even have backfired as little progress has been made toward getting rid of President Maduro. Mr. Duque had gambled that by standing up against the Maduro regime, he would win points with U.S. President Donald Trump and his administration, perhaps the most powerful and complex exogenous factor in Colombian politics. However, President Duque’s efforts to forge a positive relationship with Washington have been hampered by the increase in coca production, which displeases Mr. Trump.

Facts & figures

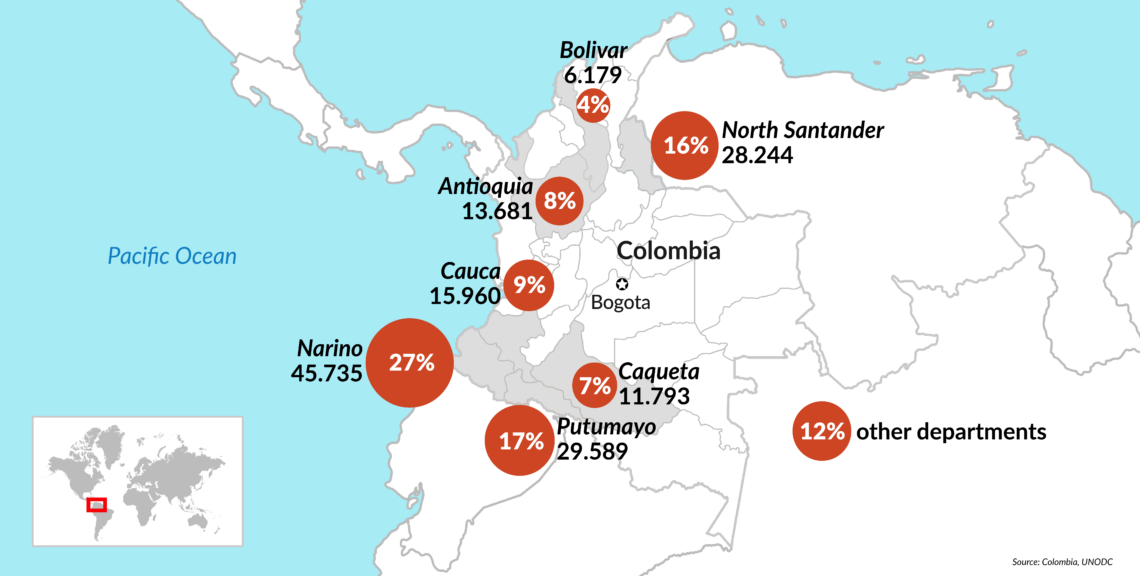

Coca cultivation in Colombia's departments

Hectares, percent of total production

This is a perfect example of how the Duque government’s domestic policies have become ensnared in geopolitics. Coca cultivation is increasing mainly in Colombia’s poorest rural areas, where the policy of crop substitution under the previous government of President Juan Manuel Santos (2010-2018) had enjoyed some success. Over the past two or three years, strong demand for cocaine in the U.S. and the reviving strength of guerrillas and armed criminal groups have boosted coca plantings.

Defoliation, the previous policy imposed by the U.S., is ill-suited to areas of smallholders and subsistence farming. Furthermore, the environmental damage inflicted by chemical defoliants has spurred significant political opposition. The Trump administration has no sympathy for Colombia’s reservations about defoliation and wants the Duque government to get on with it, threatening to end the aid program that pays for crop substitution.

Crime and corruption

To complicate matters, Colombia’s homicide rate went up in 2018 for the first time in five years. Violent crime only adds to the citizenry’s sense of insecurity and increases pressure on the government to do something. Even though the lengthy negotiations of what became the peace accord with the FARC coincided with a gradual decline in the homicide rate, the government has refused to take the logical next step and open talks with the remaining guerrilla group, the ELN. Much of the recent upsurge in crime is urban and can be attributed to organized gangs. According to government estimates, there are at least 2,200 ELN fighters, plus another 5,000 in “other criminal groups.”

The government has yet to come up with a plan to deal with the deteriorating security situation. Perhaps most disturbing is that hundreds of civil rights workers, union leaders, and members of minority groups such as Afro-Colombians, indigenous people and members of the LGBT community have been targeted for assassination by the BACRIM and other paid killers. None of these murders have been solved and very few have even been prosecuted.

The population’s other main concern is rampant corruption.

The population’s other main concern is the rampant corruption of the Colombian state. President Duque pledged to deal with this with a zero-tolerance policy. Thus far, his government has failed to follow up with specific policy measures. To the contrary, Mr. Duque nominated as the new general public prosecutor Nestor Humberto Martinez, a veteran politician who was publicly implicated in the Odebrecht bribery scandal, which has rocked at least half a dozen countries in the region. The nomination caused a public outcry and forced Mr. Martinez to withdraw from consideration.

Economic policy

Given this lack of specifics, the debate over the Duque government’s agenda has focused on economic and fiscal policy. While the details of next year’s budget have not yet been revealed, some significant hints can be gleaned from the National Development Plan (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo, or PND). This document makes clear that the government intends to raise taxes, not lower them as President Duque had promised in his campaign. Less spending will be targeted on social issues such as land restitution, dealing with the gigantic backlog of legal claims by war victims, and helping the economically vulnerable. The PND is being opposed by labor unions, private pension funds and business groups, including the National Business Association of Colombia (ANDI) and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which are calling for modifications.

Despite these policy differences, Colombia’s economy is doing well. The macroeconomic indicators are upbeat, as output growth almost doubled its pace to 2.7 percent in 2018, while the central government budget deficit and the current account deficit remained in check at 3.1 percent and 3.8 percent of GDP, respectively. Inflation also remained modest at an annualized 3.2 percent in March 2019, almost unchanged from the end of last year. One soft spot is the job market, where unemployment has begun to creep into the double digits, reaching 10.8 percent in March.

International investors seem to be taking a far more positive attitude toward Colombia than those inside the country. Assessments of sovereign risk are improving and the ratings agencies consider Colombian debt to be investment grade. Indeed, the country’s image is much better than that of many other South American economies.

Facts & figures

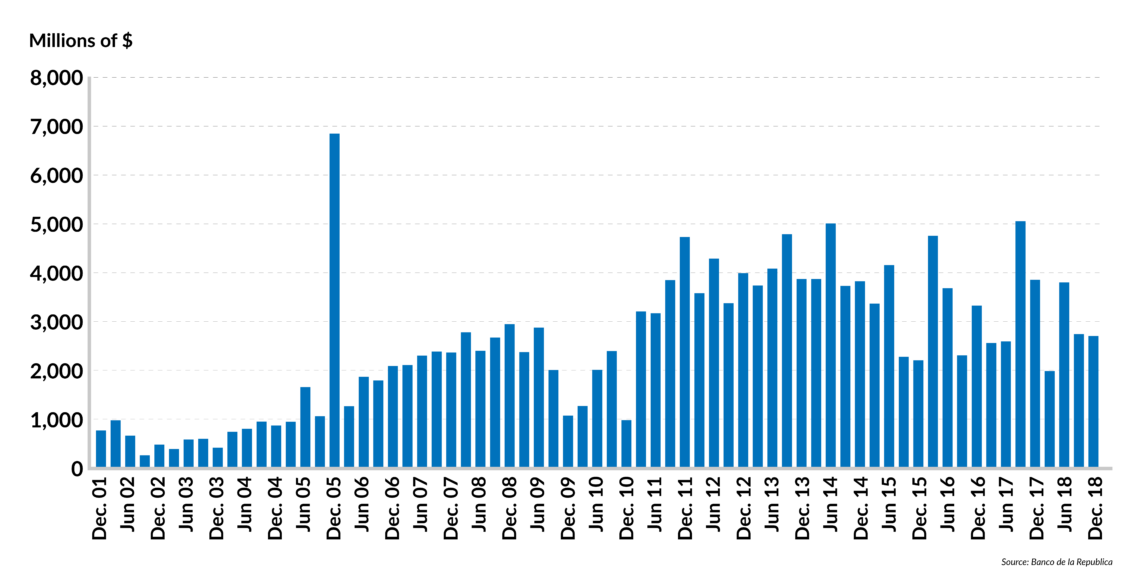

Foreign direct investment in Colombia

The Colombian economy’s strongest element is foreign direct investment (FDI). While there was a slight decline in FDI inflows during 2018, that trend reversed in the first months of 2019, with the central bank reporting a 20.8 percent increase. Investment patterns resemble those of previous years, with a heavy emphasis on extractive industries. Colombia’s extraordinary natural resources remain a key national asset.

Wooing business

The Duque government has declared its sympathy for the country’s entrepreneurs, pledging to simplify the regulatory framework and introduce reforms of the public sector that will stimulate private enterprise. The effects of these efforts will not be visible until the second half of 2019, but the business community’s skepticism about the National Development Plan does not suggest a high level of trust.

Colombia’s great economic challenge is to find a way to increase productivity and improve its international competitiveness. This will require a significant readjustment in national priorities, including new financial incentives and a simpler, more transparent regulatory framework. As in so many other areas, the lack of administrative capacity is a serious obstacle to progress and development. Internal government debates have shown policy divisions, with pro-business sympathies clashing with worries that tax cuts would only weaken the state’s capacity to help the economy. Administrative reform might be the government’s most effective economic stimulus in the short term.

A more promising development for President Duque is the hopeless fragmentation of the political opposition. This lack of cohesion was evident in the second round of last year’s presidential election, when Mr. Duque’s opponent in the runoff, Gustavo Petro, could only muster 42 percent of the vote. Mr. Petro seems to have retreated to his core support base in Bogota, the capital, and no other leader has emerged from any of the smaller center-left parties to rally opposition to the government. Even so, opinion polls show much of the public are not happy about the center-right policies being prescribed by President Duque and his political patron, Mr. Uribe. This will remain a latent resource for the opposition to tap.

Any transition to a more democratic government in Venezuela would have significant benefits for Colombia.

Scenarios

President Duque’s strategy for navigating through the next few months is reasonably clear. Most of his energy will be devoted to wooing the non-Uribe conservatives while he tries to get Congress to approve his “objections” to the peace accords (especially the JEP) and the National Development Plan. Under pressure from the Trump administration, the Duque government will probably allow some defoliation in sensitive areas with heavy concentrations of armed groups or natural resources. At the same time, the counterinsurgency effort against the ELN will be stepped up.

The latter measure could strengthen Mr. Duque’s hand in dealing with Venezuela, since the Maduro regime is giving aid and comfort to the guerrilla holdouts. Meanwhile, the violence in Caracas is worsening. This will spur more migration into Colombia, making President Duque’s work harder, but could also signal that Venezuela’s protracted crisis could be headed toward some sort of resolution. Any transition to a more democratic government there would have significant benefits for Colombia. The fall of the Maduro regime and stronger ties with the U.S. would provide an instant boost to investment in Colombia, both domestic and international. That, too, will help Mr. Duque.

Three potential developments – two of which are largely beyond President Duque’s control – could spoil this rather benign outlook. The first is the possibility of a prolonged civil war in Venezuela, which would unleash chaos in the border areas and divert the government’s attention and resources from internal reform. The second is that Mr. Uribe, frustrated in his efforts to strengthen the Democratic Center in the countryside, will turn against President Duque and shatter his ruling majority. A third contingency – perhaps a bit far-fetched but still conceivable under changing political conditions – is that Colombia’s fragmented opposition will unite and take control of Congress.

This last possibility is a double-edged sword. It would weaken the president but could have very positive implications for Colombia’s internal debate over strategic issues and public policy.